Mythical Athleticism — Ancient Greece

Terracotta Panathenaic prize amphora (jar), ca. 510 B.C. Greek, Attic. Terracotta, 24 ½ in. (62.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Fletcher Fund, 1956 (56.171.4). Public Domain (Reverse side of jar, chariot race).

From the dust of ancient arenas to the pages of epic myths, sports have been part of the human story since the dawn of time. A testament to the human drive to explore and push their abilities, sports has been invented and reinvented throughout different civilizations and cultures, and continues to do so today.

Here, we honor one of the oldest and most revered gatherings of the fastest and the strongest - The Ancient Olympics (776 BCE–393 CE).

They were far more than athletic contests—they were a philosophical celebration of human excellence. Founded in Olympia, Greece, these games were held every four years in honor of the ancient God Zeus.

There are different mythical origins related to the games: some related to Hercules, and others drawing from a more treacherous and accursed origin known as ‘Pelop’s Chariot Race.’

Of the first, they claim that Hercules (Heracles) founded the games after completing his twelve labors, staging races to celebrate his victory over King Augeas.

As for the others, they say it is to commemorate Pelops’ deadly chariot race against King Oenomaus for the hand of Princess Hippodamia.

Pelops was no ordinary prince. His father, Tantalus, tested the gods’ omniscience by killing Pelops, cooking him in a stew, and serving him to the Olympians. The gods revived Pelops, but cursed his lineage with a curse that would shape his fate.

Pelops sought to marry Hippodamia, daughter of King Oenomaus of Pisa (near Olympia). The king had already killed 18 suitors in a chariot race, for an oracle had warned he would die by his son-in-law’s hand.

Pelops did not go unprepared and undertook a few cunning steps: He bribed Myrtilus, the king’s charioteer, to sabotage the chariot; and, just in case, he replaced the linchpins with wax replicas.

During the race, Oenomaus’ chariot collapsed, dragging him to his death and fulfilling the prophecy. After the win, Pelops murders Myrtilus to avoid paying the bribe, and then founded the Olympic Games to honor Zeus and atone for his crimes.

Every Olympic chariot race carried echoes of this deadly duel—where victory walked hand-in-hand with treachery, and sometimes, even the gods played favorites.

Despite these violent mythical origins, at the core of every leap, every race, and every handshake between rivals lies the timeless spirit of the Olympics— excellence, courage, determination and (perhaps surprisingly) friendship.

Whatever its origin, the Olympics continue to inspire us. The French nobleman and historian Charles Pierre de Frédy, also known as the Baron de Coubertin (1863–1937), was inspired by the ideals and story of the ancient olympics, and revived the Olympic Games for the modern world. His legacy transcends athletics—he crafted a global movement blending sport, culture, and education to promote international unity.

In 1896, the first modern Olympic Games was held in Athens, Greece, in honor of the birthplace of these amazing games.

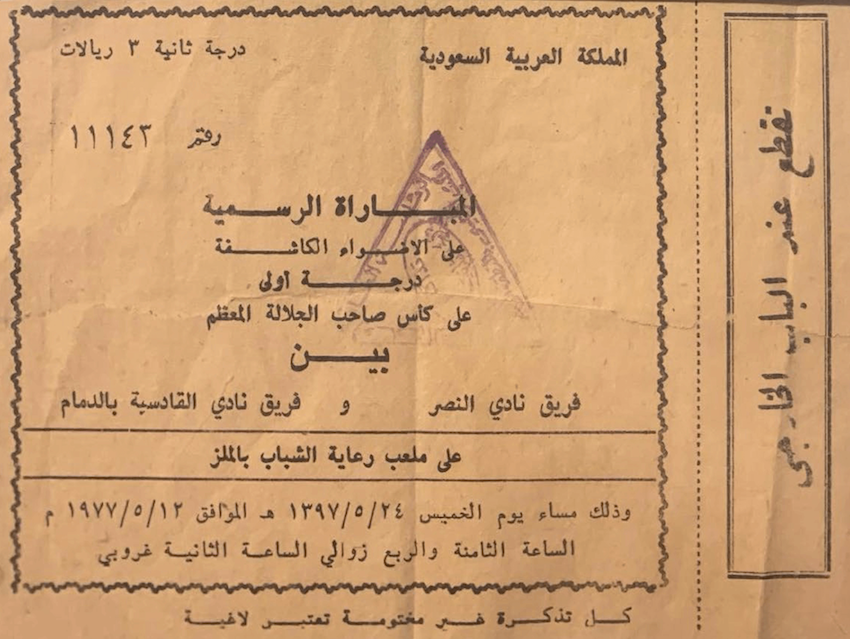

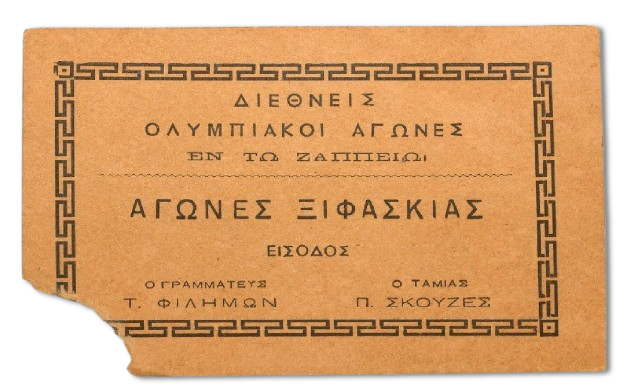

Athens 1896 Olympic Ticket. Period: 19th Century CE. Paper, Ink. Technique:Printing Dimensions:7.9 × 11.9 × 0.1 cm. Part of the 3-2-1 Qatar Olympic and Sports Museum collection. Courtesy of the Qatar Museums Online Collection initiative.

Many of the ancient Olympic core values still define the Olympic movement today, where the International Olympic Committee enshrines three fundamental values that transcend sports: excellence, respect, and friendship.

“More than just ideals, these principles form the living blueprint for using athletic competition as a force for global unity,” the committee states.

Just like the stories the Olympics inspire, the prizes have changed over the years, as we see here from the Roman era and from the Panathenaic festivals. Still, the ultimate prize will always remain the participation in mankind’s greatest games.

Enjoy discovering more about the prizes.

From the second quarter of the sixth century B.C. onwards, winners in the contests for the Panathenaic festival in Athens were given a standardized vase containing about forty-two quarts of olive oil from sacred olive groves in Attica.

The official decoration on the front was that of the Goddess Athena, fully armed, standing between two columns. The event for which the vase was awarded was illustrated on the back.

In this instance, it was the prize of a victor in the prestigious, yet dangerous, chariot race.

Terracotta Panathenaic prize amphora (jar), ca. 510 B.C. Greek, Attic. Terracotta, 24 ½ in. (62.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Fletcher Fund, 1956 (56.171.4). Public Domain (Obverse side of jar, Goddess Athena).

This exquisite Roman relief captures the essence of victory in classical antiquity, depicting the iconic prizes from four legendary Greek competitions (from the right to left): a Panathenaic amphora brimming with Athenian olive oil, Isthemian's fragrant pine wreath, Argos' gleaming bronze shield, and Nemea's humble celery crown. Far from mere tokens, these accolades—particularly the sacred foliage crowns like Olympia's olive wreath—carried almost mythical prestige surpassing their material value, embodying the priceless spiritual honor of athletic triumph.

Marble relief fragment depicting athletic prizes, 2nd century A.D. Roman. Marble, 12 ¾ × 26 ½ in. (32.5 × 67.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Rogers Fund, 1959 (59.11.19). Public Domain.