A Story of Architectural Treasures

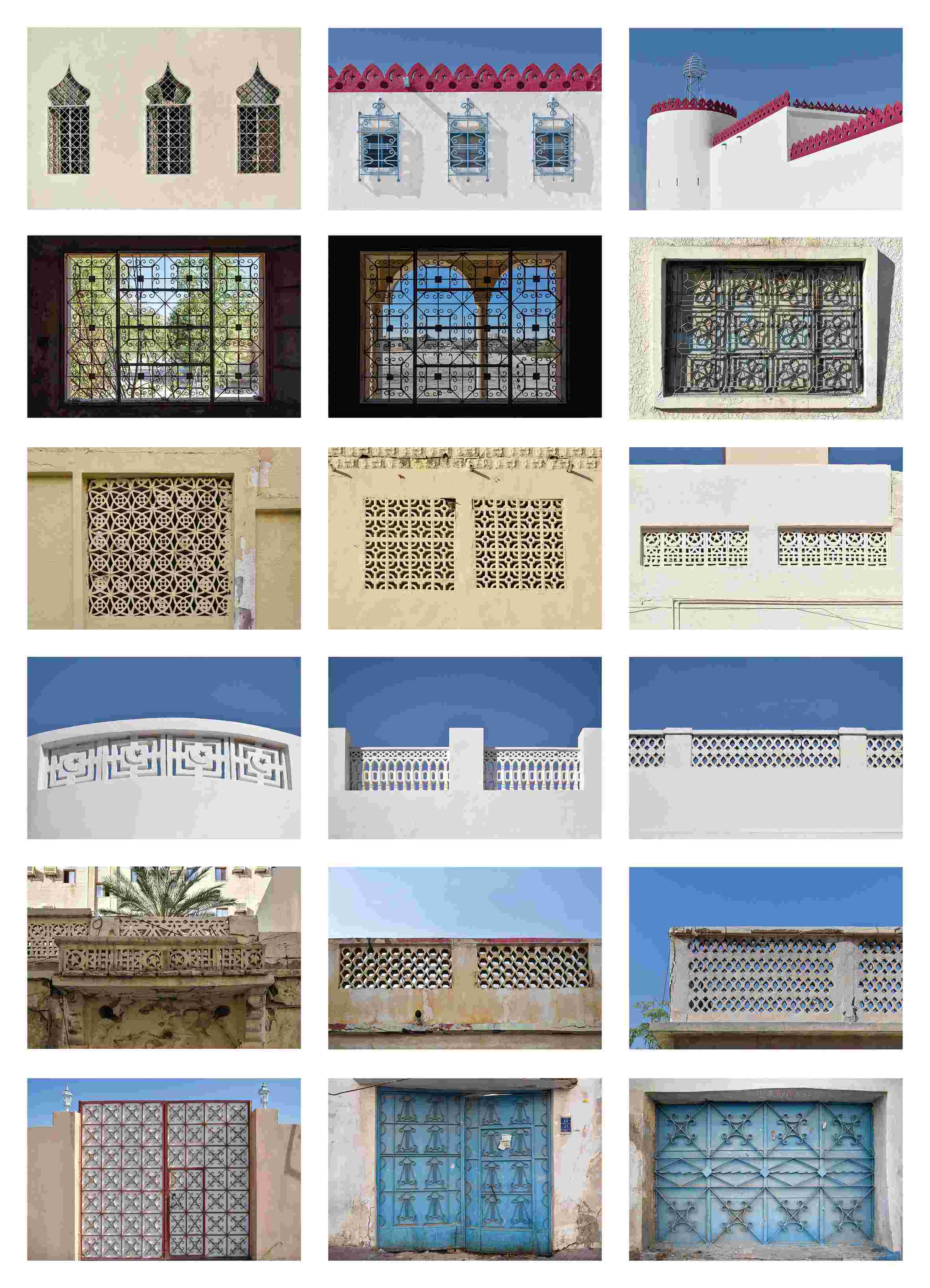

Nine portals typical of Doha and its suburbs from Wakra to Rayyan, 1950s–1960s. Photos by Péter T. Nagy, © Qatar Museums.

Rich with stunning imagery of historical buildings and gates, Design Doha’s Colors of the City exhibition tells the architectural story of Qatar’s capital over the last 100 years. The exhibition was curated by Glenn Adamson and Peter Nagy to include 3D models, films, photos, and interviews presenting the architectural transformations of the city, from before the discovery of oil and through to the arrival of global influences. The exhibition took place from February 24 to April 30 of 2024 as part of Design Doha, a biennale celebrating creativity in the region while focusing on Qatar’s design scene on the global stage.

We take you on a journey to visualize the architectural transformation of Doha—with a special focus on its enchanting gates—through the words of the exhibition’s co-curator Peter Tamas Nagy.

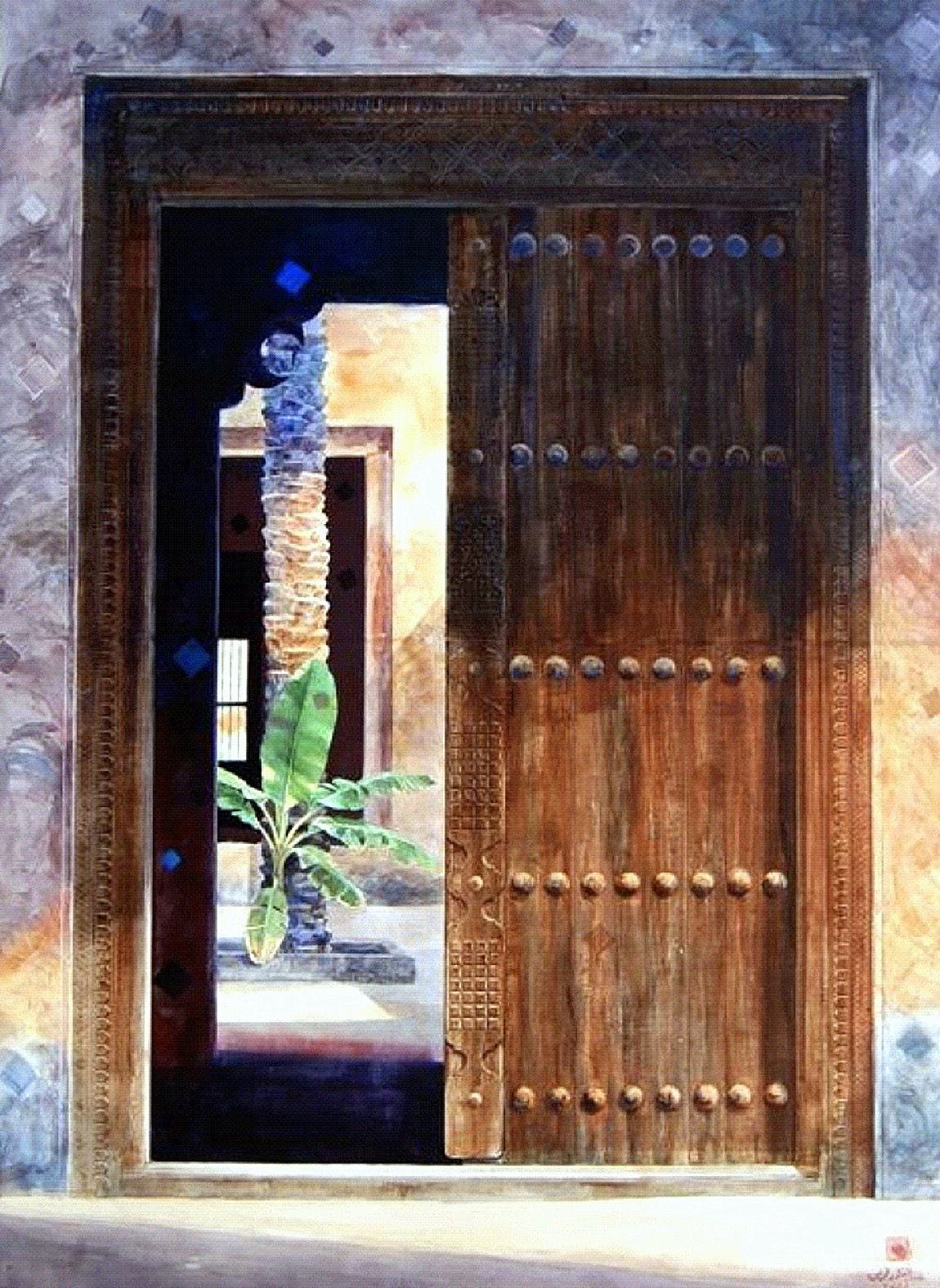

South portal, palace at Umm al-Amad,1960s. Photo by Péter T. Nagy, © Qatar Museum.

Colors of the City sought to constitute the local foothold within the cluster of exhibitions that opened simultaneously at M7, Doha. Its conception required a visionary like Glenn Adamson, artistic director of Design Doha Biennial, who wished to create a show specific to Qatari (architectural) design. Since my work entailed studying heritage architecture in the country, he invited me to participate. I still think he was overly trusting as I had no background in curatorial affairs – in other words, he threw me in deep water. I could devise a narrative based on my research at relative ease, yet the task of bringing architecture into a gallery space in a way that is visually pleasing and informative was entirely new to me.

When I first drafted a preliminary checklist of what to incorporate in the display, it already included countless photos, architectural drawings, videos, 3D models, construction materials, art objects, maps, etc. I gave no easy task to the designer company Mind the gap, namely Karl Bassil, Carla Khayat, and Elie Mouawad. However, they dexterously created this visual experience where you follow the path defined by the hanging banners – displaying text, photos, and maps – while glancing at additional exhibits on the floor and the walls, always related to the information you encounter.

This city has a history of two centuries, of which the exhibition presents the second. The display invites visitors to experience four trends of architectural and decorative design. It begins with traditional constructions from before the discovery of oil, which we display chiefly in the form of a 3D reconstruction of the Old Palace.

Then, the focus is more on the early modern period, the 1950s and 1960s, when two distinct design principles manifested in the elite residences, respectively labeled Doha Deco and Doha Classicism. The colorful decorations of this period were both unprecedented and subsequently unfollowed, which also gave the idea for the title Colors of the City. Then, the decades following Qatar’s independence in 1971 set out for a new wave of international design principles, which we condensed in the section titled Doha Brutalism.

These are the four trends highlighted in the historical part of the exhibition, followed by the contemporary part curated by Glenn. There, we decided to display a selection from the oeuvre of Ibrahim Jaidah and his company, Arab Engineering Bureau, who have made an extremely rich contribution to Doha’s skyline over the recent decades.

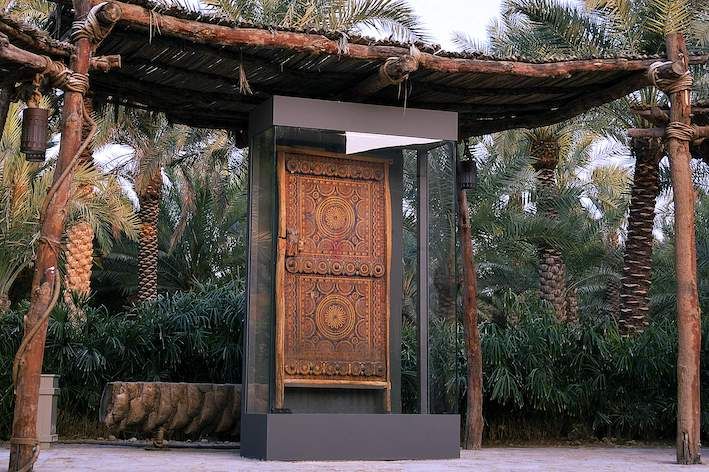

West portal, palace of Sheikh Nasir bin Hamad, built before 1959. Photo by Julián Velásquez, © Qatar Museums.

West portal, palace of Sheikh Suhaym bin Hamad, built before 1959. Photo by Julián Velásquez, © Qatar Museums.

There were many. Although the research is still ongoing, I can say that the 1950s and 1960s was a particularly complex period in that regard. The two major findings so far are the artistic links with India and Iran.

Regarding the former, it seems that the buildings presented under the label Doha Deco grew out of three registers of artistic elements: Art Deco, South Asian, and local. Chevron motifs and eye-brow ledges appeared alongside palm trees and falcons.

As for the links with Iran, a group of buildings in and around Doha feature Classicist vases and tendril motifs, which were then also combined with Arabic epigraphy, bulbous rose flowers, and so-called aina-kari (or mirror work), which were typical of Iranian architectural decoration. Studying these elements opens a line of questions about the identities of those artisans who found employment in Qatar, where several members of the royal family and other wealthy patrons were keen to recruit them to beautify their homes.

From the 1970s on, the architectural movements of international modernism also appeared in Doha, establishing a new standard of design. Driven by the motive to expand and modernize the city, Emir Khalifa bin Hamad invited renowned architects from around the globe to contribute to the new cityscape; various new landmarks from the period still align today along the Corniche Road. The key contribution brought in by the foreign designers was the most up-to-date construction techniques; the iconic Sheron Hotel applied a steel skeleton cladded in prefabricated concrete elements. Many architects also aspired to reinterpret classical forms of Islamic architecture in a modernized fashion, which we can witness most characteristically on the campus of Qatar University.

West portal, palace of Sheikh Fahad bin Ali, completed c. 1962. Photo by Julián Velásquez, © Qatar Museums.

The entrance to a house is the main point of communication with the outside world, both physically and metaphorically. It is hardly an exaggeration that Qatari patrons considered the public entrance the most important part of the entire residence and, therefore, spent a considerable sum on their decorations, recruiting foreign artisans who knew how to impress visitors and passers-by alike.

In several examples, even a modest house had an out-of-proportion portal with elaborate and colorful ornaments and lights. In a period when electricity was new to Qatar, countless portals incorporated light tubes and bulbs in their design composition. Those structures conveyed a clear message, in some cases ostentatiously showing off the owner’s riches.

Although a semantical analysis of these gate buildings has yet to be carried out, it seems that a Qatari audience would interpret them as signs of respect and status, with little intertextual associations of the specific shapes and forms. This trend, however, disappeared already in the late 60s, presumably for social reasons: not everyone was happy with those showy gates.

East portal, palace of Sheikh Nasir bin Hamad, built before 1959. Photo by Julián Velásquez, © Qatar Museums.

It is challenging to pick one since the reason I included all these buildings in the exhibition is that I find them equally fascinating. Nonetheless, the story behind that of Sheikh Ghanim bin Ali struck me the most. It still retains its decorative entablature today, but old pictures show that a pair of fish statues surmounted the structure originally.

When I began investigating those statues, I soon found myself walking down the streets of Lucknow, a lovely city in India where hundreds of heritage buildings feature similar pairs of fish sculptures on their façades. It was initially a royal symbol for the local rulers and continued to be used well into the 20th century. Although we don't know why the same iconographic element resurfaced in Doha, the analogy makes this link highly plausible; even the physical characteristics of the animals are closely comparable.

In short, artisans well-versed in Art Deco constructions traveled from Lucknow to Doha and found patronage there.

It is stimulating to see Colors of the City living its own life. There is quite some public interest in the exhibition; all my tours have been fully booked so far, and people are often happy to share their own stories about some of the buildings. I could not have expected this popularity, primarily since many of the buildings on display were previously known only to a few experts, if at all.

What I hope is that visitors will acquire a better understanding of why these buildings matter today and why they need to be preserved. The displayed examples are relevant not only because no architectural historian enjoys studying demolished buildings, but also because, as long as they exist, they can continue educating us about the cultural interactions of the period.

I believe that learning about art – or material culture in the broadest sense – can contribute to how we place ourselves in the cultural cosmos of today. In the case of Colors of the City, it consciously embraces this cosmopolitan and multi-layered heritage, narrating a historical trajectory unique in the region.

East portal of the (now demolished) house of Hamam Al Abd Allah, completed c. 1965. Photo by Julián Velásquez, © Qatar Museums.

East portal, palace of Sheikh Ghanim bin Ali, completed c. 1965. Photo by Julián Velásquez, © Qatar Museums

Decorative details of architecture in Doha and its suburbs, 1950s–1960s. Photos by Péter T. Nagy, © Qatar Museums.