Finding Art After the Rain - Diriyah Contemporary Art Biennale

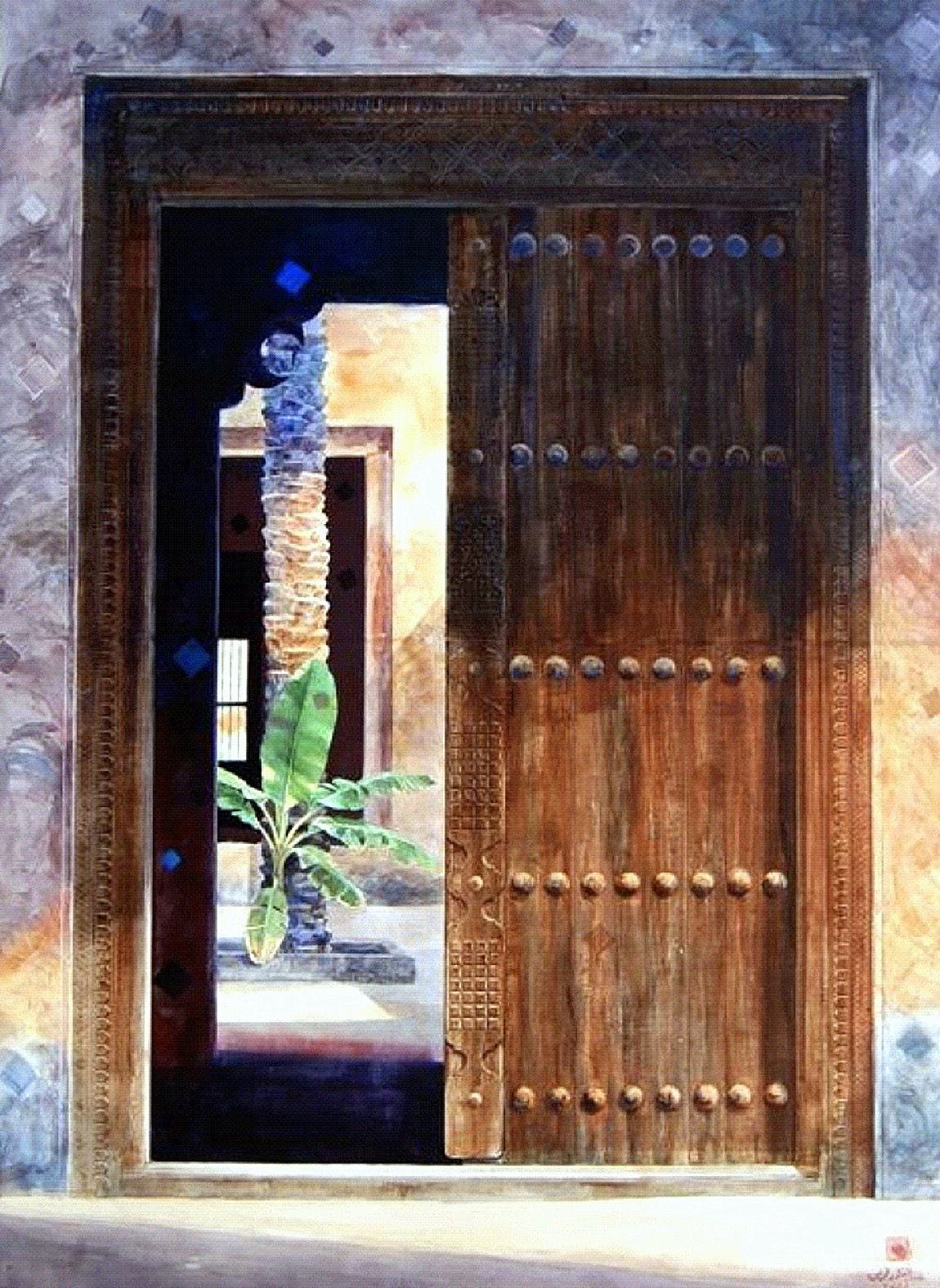

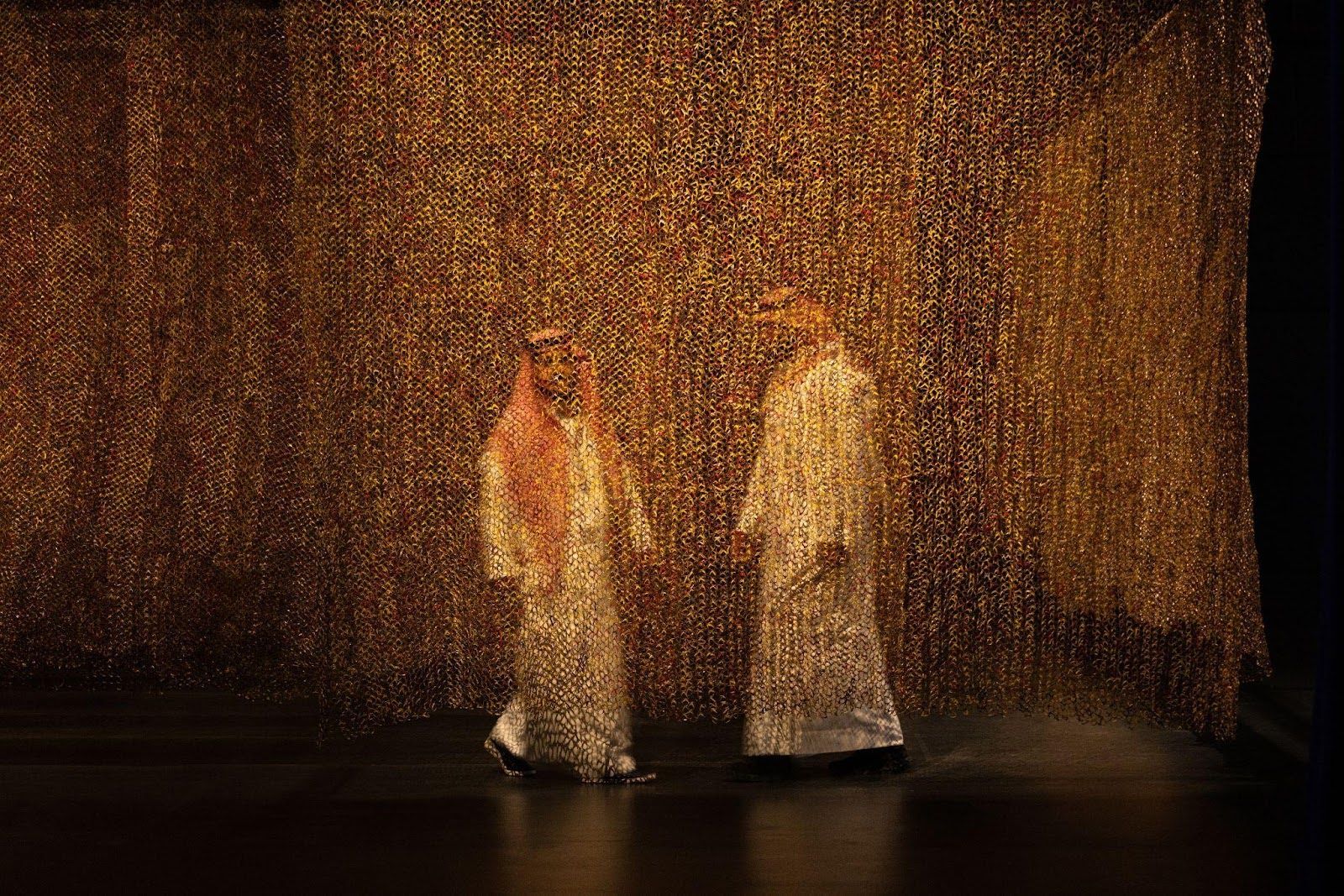

Dana Awartani, Come, Let Me Heal Your Wounds (2020), Courtesy of the Diriyah Biennale Foundation, photo by Marco Cappelletti

Rain is an event that naturally breathes renewed life into our world. The moment that follows rainfall is one of pause and reflection—the earth is rich with rainwater, the flora is covered in delicate droplets, and the sky—as well as everything else—is vibrant with that evocative scent and color of rain.

The 2024 Diriyah Contemporary Art Biennale, After Rain, asked us to experience this illuminating moment more closely through a variety of artistic formats, perspectives, expressions, and backgrounds.

Organized by the Diriyah Biennale Foundation and curated by Artistic Director Ute Meta Bauer, this edition presented 177 artworks by 100 artists and groups—30 were from the Gulf region—evoking sensations of renewal, revitalization, and opening up.

The Ithraeyat Editorial Team sat down with lead curator Ute Meta Bauer to bring you a deep dive into the journey of creating this biennale, the concept behind “After Rain” and its connection to the natural landscape of Diriyah, and some of the experiences that it offered to both its artists and visitors alike.

It all started with my first-ever trip to Saudi Arabia in 2018, on which I was told about the plans to create a biennale in Riyadh. I was, of course, unfamiliar with the art scene in Saudi at the time, since it wasn’t a country I visited before 2018. The proposal to curate the second edition interested me as an opportunity to inquire into what a biennale could contribute to this moment of transformation. On this trip, I did studio visits with Dana Awartani as well as Nasser Al Salem in Jeddah, where I also met Sara Abdu. I wondered about how to curate a biennale from scratch, how that can work in the Kingdom, and what is possible to show to an audience that is new to art. To me, it was driven by and born out of curiosity.

Wejdan Reda, who was an assistant curator in the first edition and is a curator at Diriyah Biennale Foundation, has been such an insightful guiding source for me since the beginning of this project.

She was instrumental in the process of meeting local artists of different generations across Saudi Arabia. The Diriyah Biennale Foundation was also very generous in enabling us—the curators and artists—to go on trips to different regions in the Kingdom, to visit artists’ studios and talk to a variety of people, as well as visit neighboring countries like Kuwait, Jordan, and Bahrain.

My ambition was to create a biennale that not only speaks to the current moment of time but also to the art scene and through the art scene, as well as to a wider audience, who are discovering art now as part of their everyday life.

After Rain, Diriyah Contemporary Art Biennale 2024, installation view, Ade Darmawan, Tuban (2019), front; Christine Fenzl,* Women of Riyadh (2023), background. Photo by Alessandro Brasile, Courtesy of the Diriyah Biennale Foundation.

It’s not necessarily a theme; rather, it’s a title. After Rain is inspired by Arabic poetry, and since the Arabic language is very difficult to translate to English (and vice versa), we tried to come up with a title that the Arabic-speaking local audience—the one that the biennale is most geared towards—would resonate with. A title that encapsulates what we were trying to do with the biennale.

For me, it’s very important to understand the audience and take a moment to think about what they would take with them from this biennale, and the topics we address in After Rain. When rain has just fallen, and it takes place across the world, the smell is just mesmerizing. It’s an incident that affects our biochemistry—when rain falls on dry soil, aerosols are released carrying the earthy scent called “petrichor,” which is regarded as an antidepressant. In any case, it’s a very optimistic moment, a moment of energy and hope.

Worldwide, we are not in a very hopeful place. From the global climate crisis to economic issues and armed conflicts, there is a lot of suffering at the moment. But I feel such good energy when I come to the biennale site; there are so many young people who want to express themselves and their desires through art. After Rain acknowledges that the world might not be at the best place, but also that we obviously need a sense of hope and of a future.

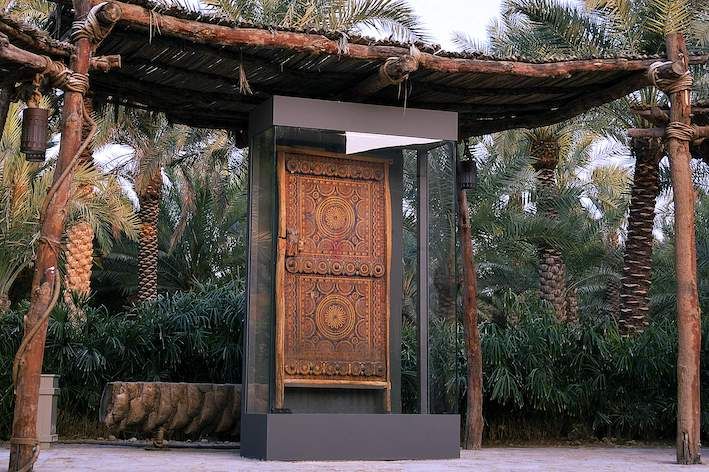

After Rain, Diriyah Contemporary Art Biennale 2024, installation view, El Anatsui, Logoligi Logarithm (2019), detail. Photo by Alessandro Brasile, Courtesy of the Diriyah Biennale Foundation.

Diriyah is an older town than Riyadh. Today, it has the UNESCO World Heritage Site of At-Turaif—the seat of the house of Saud. It sits at the edge of Wadi Hanifa, a seasonal riverbed, and of course, it’s situated in a desert region. In every arid landscape, rain is desired. The soil literally waits for rain to fall, allowing the moment when everything pops up. Metaphorically, it’s a moment of revitalization and renewal. It’s an energy that you really feel when you’re here in Jax. As curators we were challenged but also grateful for the complex task of working with such a large number of artists, and that we could initiate such an amount of new commissions. It gives us the feeling that we were able to energize people emotionally, and with that energy, you can move mountains.

After Rain, Diriyah Contemporary Art Biennale 2024, installation view, Armin Linke & Ahmed Mater, Saudi Futurism (2024). Photo by Marco Cappellettii, courtesy of Diriyah Biennale Foundation.

The biennale was created by a curatorial team; I’m more senior, for example, as a curator and then we have mid-career and younger curators. We have all experienced different moments of time when we were studying and discovering the context and culture we live in. We undertook research trips joined by local and international artists to see Asir and Abha, in the southwestern part of Saudi, which most of us visited for the first time. It has been an incredible and exciting journey on which so much knowledge was unlocked. We were all like, “we want to share this journey with the audience.” The exhibition itself hopefully feels like a journey with us sharing what we’ve experienced while researching for this biennale.

After Rain is designed to be a multi-sensory experience that invites viewers to think about what all this art is about, and what experiencing it does to them. We not only wanted to tell the audience something through the biennale; we also wanted them to tell us something.

After Rain, Diriyah Contemporary Art Biennale 2024, installation view, Samia Zaru, Life is a Woven Carpet (1995), front left, and Life is a Woven Carpet (2001), front right; multiple works by Abdulrahman Al-Soliman and Hind Nasser in background. Photo by Marco Cappellettii, courtesy of Diriyah Biennale Foundation.

It’s very hard to choose any single artwork because I really love them all. It’s like asking what instruments one likes in an orchestra—a drum, a violin, or a flute—which is hard to choose as you can’t isolate one from the other in a composition. I highly recommend the biennale as a holistic journey.

To me, all artworks in the biennale are meant to inspire people to be curious. For the newly commissioned works, we asked the local, regional, and the other participating artists to tell us what they see when they are visiting Saudi and what they want to tell the public about this place through their perspective. Also, what conversations they wish to steer. All visitors are invited to experience these artists’ perspectives, start a dialogue with the work of art, and feel free to ask questions. The biennale is meant to encourage people to talk to each other but also understand things on a more personal level. We do not want the audience to feel that they aren’t knowledgeable enough or that they are not experts in art or art history.

That one is interesting. I asked two artists, Saudi artist Ahmad Mater and Berlin-based photographer Armin Linke, to work on something together for this biennale.

I thought it could be good to start a conversation about image production in Saudi. Like, what images are produced right now? What images have been produced in the past? The two artists went, for example, through the archives of Aramco and through Ahmed’s contacts; they had very generous access to the Saudi Space Agency. I didn’t know Saudi had a space program!

They also looked up architecture that was built in the 1970s and visited the site where NEOM is constructed. So, this work is asking, what is the image that one wants to create about a place or a country? What exactly is image production? The two artists photographed together but also individually explored various sites in Saudi as well as images about Saudi Arabia featured elsewhere.

Yes, many, but they are not necessarily artists who have never exhibited their works before, since participating in a biennale requires you to have some experience in presenting your work. What I mean is that there were some senior artists who have a lot of experience with exhibitions but not with biennales in particular, as this is only the second edition in the Kingdom. Nabila Al-Bassam, for example, is very well-known in the Kingdom and has been running the Arab Heritage Gallery for 50 years now. She makes these beautiful architectural compositions out of tribal textiles, and her work is indeed well-known locally but maybe not yet internationally. So, the biennale intends to also offer this exposure for artists who were active since the 1960s.

The idea of contemporariness is important to me. What does the contemporary mean? There are quite a number of local artists who were young and also had fresh minds in the 1970s and 1980s. They had to do their work at a time when it was not so easy to be an artist. There was no art market or the infrastructure found in Saudi today. This generation, to me, is very fresh and they are “contemporary” artists. A younger generation of artists like Sara Abdu, a Jeddah-based artist with Yemeni roots, presents works created for this biennale on a much larger scale or are newly commissioned, so of course, no one saw them before.

Well, I come from a background of teaching at technological universities such as MIT in the U.S. and currently NTU in Singapore. I see AI as a techno-scientific development that we probably must live with, and like with all technology, it depends on what you make out of it. Technology is helpful to us—to a certain degree—but it also can have its downsides. It is important as AI currently develops further that we understand its complexity and impact on everyone’s life. To me, AI is an invention that can revolutionize our lives, but I wouldn’t say its impact is completely different in scale and scope from the introduction of airplanes, telephones, fax machines, or computers. Each of these “inventions” has obviously transformed how we live together and communicate with each other. But we’ll have to wait and see how AI will influence the way we live.

As we bid farewell to this year’s contemporary art biennale in Diriyah, we look forward to the new stories and experiences that the next one will bring—the same way the revitalizing moment of “After Rain” leaves us eager for the next round of rain.