Interconnected Imagined World - Latin American Art

Frida Kahlo’s Autorretratocon chango y loro (Self-Portrait with Monkey and Parrot) 1942, Malba Collection Eduardo F. Costantini Donation, 2001. Courtesy of Qatar Museums’ part of their landmark Latinoamericano | Modern and Contemporary Art from the Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires (MALBA) and Eduardo F. Costantini Collections exhibition, the first of its kind in the region. It was held from 21 April to 19 July 2025.

There is something very special about Latin American art.

Mythical, symbolic, raw, peppered with expressions of identity and ideas and realities, one can’t help but marvel at the breadth and width of art born of a region so diverse and multicultural. It is a magical world of its own.

An iconic example is the art of the revolutionary Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, featured here, whose creative expressions so blurred the lines between realities, dreams and raw truths, that she can’t be boxed into any one category. She herself rejected any labels of surrealism when describing her artworks.

“I don’t paint dreams or nightmares. I paint my own reality,” Frida is quoted as saying.

In this special artwork that was on display at the National Museum of Qatar as part of a partnership with Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires (MALBA),we see one of Frida’s recurring characters, her beloved pet companions.

Fulang Chang, her mischievous spider monkey, appears wrapped around her neck in most of her portraits, while the vibrant colorful parrot is perched like a living jewel in this 1942 magical art piece called ‘Self-Portrait with Monkey and Parrot.’

Elements from her mixed heritage are also captured in this piece, such as indigenous Tehuana-inspired braids. Born to a German immigrant father and a mother of mixed Spanish and Indigenous Tehuana ancestry from Oaxaca, Frida crafted unique multilayered and timeless identities and stories in her art that defied simple categorization.

With bold sartorial choices that ranged from traditional Tehuana huipiles to European haute couture, she performed in her art a constant dance between cultures, as well as between imagined and realistic worlds.

Through her self-fashioning, Frida challenged rigid notions of heritage, creating a personal mythology as complex as Mexico's own postcolonial identity.

Her genius lay in this art of alchemy, turning the very real creatures of her home, her Casa Azul, into universal symbols of resilience and friendship.

As she wrote: "Feet, what do I need you for when I have wings to fly?" — a sentiment embodied by the parrots and monkeys who, in her art and life, represented the freedom her broken body was denied.

Remedios Varo, Armonía (Autorretrato sugerente) 1956. Courtesy of Qatar Museums’ part of their landmark MALBA and Eduardo F. Costantini Collections exhibition.

Stricken with polio as a child, then nearly killed in a horrific 1925 bus accident that shattered her pelvis and spine, Frida spent her life in unrelenting pain. Confined to bed during endless recoveries, she turned to art—not just as an outlet, but as a vital act of survival.

With a mirror suspended above her bed and a small easel in her lap, Frida’s imagination became her escape and her weapon. She transformed her suffering into surreal, symbolic masterpieces where fractured bodies sprouted roots, monkeys and animals became guardians, and tears bloomed like flowers.

“Frida is telling her own personal story with this piece,” Issa Al Shirawi, one of the curators of the exhibition, told Ithraeyat.

“She is her own multicultural figure, represented by her braids, her clothes; together with her companions and symbols of Latin America, the parrot and the monkey, she is showing the world she is more than her relationship with her husband, the artist Diego Rivera, who is best known for his large-scale Mexican Mural Movement,” he said. “You get to appreciate Frida as a great artist in her own right.”

The quipu is “a poem in space, a way to remember, involving the body and the cosmos at once,” said Chilean artist Cecilia Vicuña. Quipu desaparecido (Disappeared Quipu) is a multi sensory installation created in 2018, using wool and video projection with sound. Part of the Eduardo F. Costantini Collection. The Andean civilisation developed quipus —knotted strings comprised of coloured, spun and plied wool or llama hair— as a method of recording information. This practice documented various aspects of societal organisation across the ancient Incan Empire, including tax obligations, calendrical information, and military planning. Quipus were also used to record poems and historical narratives. Inspired by these threads, the artist created this piece as an homage to ancient people and their ways of life decimated by Spanish colonization.

Photo by Rym Al-Ghazal, featuring curator Issa Al Shirawi, at the LatinoAmericano exhibition at the National Museum of Qatar.

“The whole world knows Frida, so come see her art, and then discover all the rest and diverse artists whose art speak a multitude of stories, some indigenous, some mythical and some inspired by nature and their realities and events. Whatever the subject matter, the Latin American artworks speak the universal language of the heart and beautifully resonate with all of us as they awe us with their magic and colors,” said Al Shirawi.

The landmark exhibition was the first large-scale presentation of Latin American art in the West Asian and North African regions. Exhibited at the iconic National Museum of Qatar, the exhibition provided an overview of the artistic production of the continent through works by key artists from 1900 until today. The exhibition formed a cornerstone of the Qatar Argentina and Chile 2025 Year of Culture.

Curated by Al Shirawi and Maria Amalia Garcia, the exhibition was organised in five thematic sections, and presented more than 170 artworks of different types that explored Latin America’s shared natural landscapes, the plurality of its identities, the development of its cities and urban landscapes, the strong social tensions, and the emancipatory artistic process unique to the continent.

“Imagination and art has no limit…and art helps us see that we are more interconnected than we realize, despite great geographical distances and language differences,” said Al Shirawi.

A truly magical exhibition, you can explore its art here at the National Museum of Qatar, and some of the featured artworks from MALBA can be explored on Google Art & Culture.

Antonio Berni's "El pájaro amenazador" (The Menacing Bird) is a ‘polymateric’ construction from his "Monstruos cósmicos" (Cosmic Monsters) series. Created in 1965, it is a large-scale artwork composed of various materials including wood, bronze, wicker baskets, straw, sponge, plastic, enamel, and twigs. Courtesy of Qatar Museums’ part of their landmark MALBA and Eduardo F. Costantini Collections exhibition.

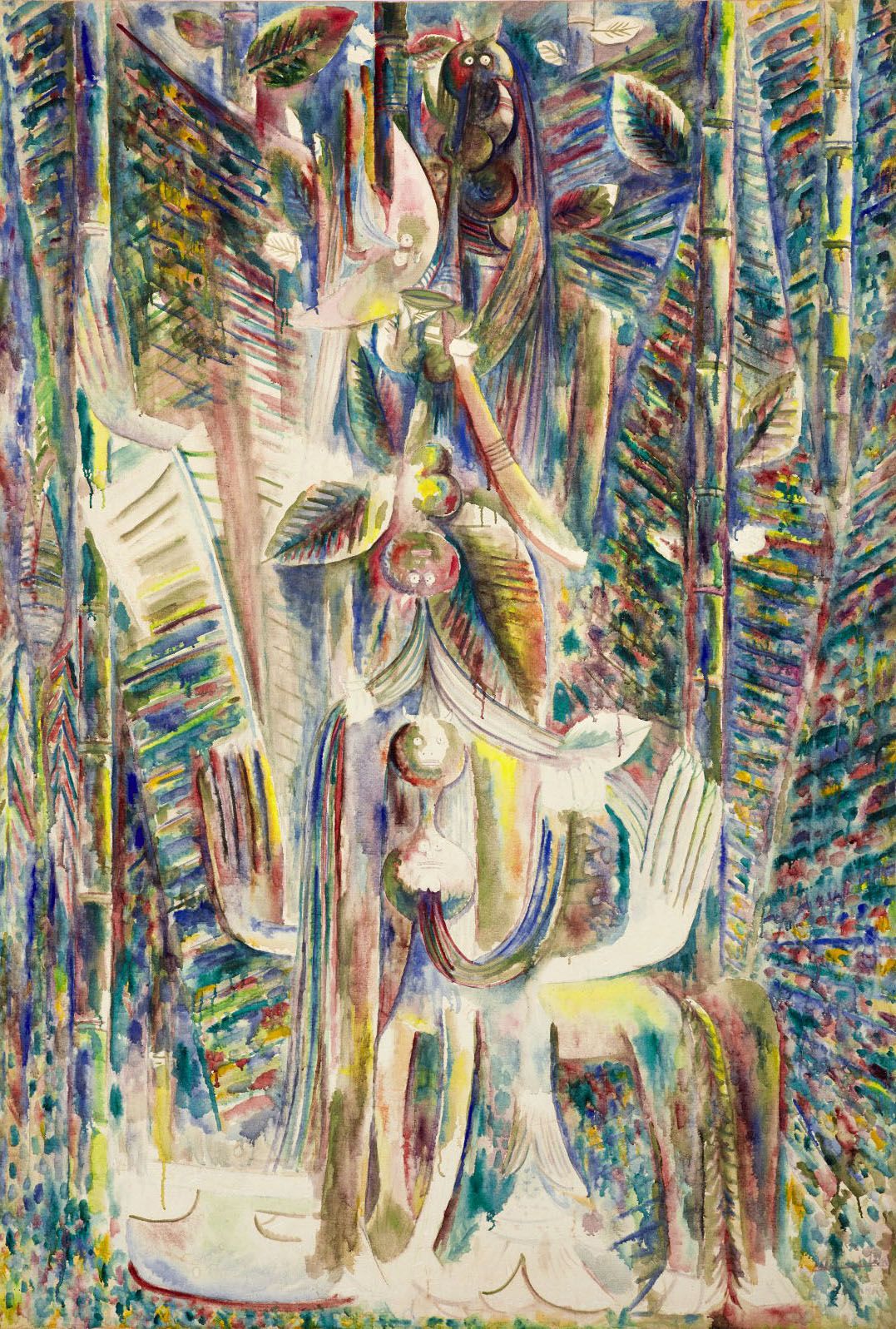

Miguel Covarrubias, ‘Paisaje exuberante o Jungla’ (Exuberant Landscape or Jungle), 1935, gouache and watercolour on paper. Malba Collection. Miguel Covarrubias / SOMAAP, México/SAVA, Argentina. Photo by Oscar Balducci. Courtesy of Qatar Museums’ part of their landmark MALBA and Eduardo F. Costantini Collections exhibition.

Vicente do Rego Monteiro, ‘El Oso,’ 1925. In a palette of ochres and browns inspired by the ceramics of the Amazon and with the faceted volumes and forms of cubism and futurism, do Rego Monteiro depicted here a unique golden bear, native to northeastern Brazil also known as the “pygmy anteater” — the smallest bear in the world. Courtesy of Qatar Museums’ part of their landmark MALBA and Eduardo F. Costantini Collections exhibition.

Alice Rahon, Autorretrato (Self-Portrait), 1951, oil on canvas. Courtesy of Qatar Museums’ part of their landmark MALBA and Eduardo F. Costantini Collections exhibition.

Fernando Botero, El viudo (The Widower), 1968, oil on canvas. Malba Collection. Eduardo F. Costantini Donation, 2003. Credit: The Fernando Botero Foundation, 2025.

This ‘tragicomedy’ artwork, with the absence of the mother-wife, to whom an altar has been consecrated with her youthful image, a candle and a rosary set against the tearful faces of all the characters in the scene, including the dog, comments on the cold and inexperienced maternal attitude of a father in a Latin American society that grants this role exclusively to women.Courtesy of Qatar Museums’ part of their landmark MALBA and Eduardo F. Costantini Collections exhibition.

Wilfredo Lam’s ‘Omi Obini,’ 1943. It is one of the oil paintings most representative of his work with the vegetable- human-divine syncretism. It depicts a levitating being; its body contains horned heads of Elegua, the goddess of roads in the Yoruba religion; it is surrounded by stalks of sugarcane and palm leaves. It vibrates and shines, creating a timeless art of magic. Courtesy of Qatar Museums’ part of their landmark MALBA and Eduardo F. Costantini Collections exhibition.