An ode to colorful joy

“Colors are light’s suffering and joy…” Johann Wolfgang von Goethe marveled at color’s occurrences, their meanings and uncovering their secrets and impact on human reaction. His research marks the beginnings of modern understanding of color psychology. He poetically described each color, with yellow —considered by many the color of joy —being “the color nearest the light…In its highest purity it always carries with it the nature of brightness, and has a serene, gay, softly exciting character.”

The bass is the first to sing the word, declaiming “Freude!” (Joy) from the ranks of the choir. Just this one word, not an entire fully-formed sentence,

two syllables on two identical tones, and still somewhat tentatively. And then once again, this time more resolutely:

“Freude!”

This optimistic sentiment as the stipulated ideal, joy serving as a counterpoint to all the melancholy, doom and gloom that has been exuded by the

instruments in the three preceding minor key phrases.

In the final movement of his ninth and last completed symphony, Ludwig van Beethoven, whose 250th birthday we commemorate this year, powerfully addressed a topic that had been on his mind for years.

Published in 1786, Friedrich Schiller’s poem “Ode to Joy” had made a considerable impression on him. The poem expresses Schiller's idealistic vision of the human race becoming brothers - a vision Beethoven shared. The composer already penned an initial scoring in 1815, a full nine years before the work was premiered. Today Beethoven’s Ninth is famous around the world. It has also found its way into the world of pop,

as well as into literature – it is featured for example in the novels “Doctor Faustus” by Thomas Mann and “Clockwork Orange” by Anthony Burgess, which Stanley Kubrick turned into a film in 1971. Its melody, in an arrangement created by Herbert von Karajan, was declared the Anthem of Europe, first in 1972, by the Council of Europe and again in 1985 by the European Union.

The enthusiasm of the final movement of the symphony reflects the pathos that is also inherent in Schiller’s poem: “All men become brothers. Through the bonds of friendship and joy, there is a “bright spark of divinity,” and all humans are united in an equal society – that at least, is the ideal in the classicist period. In Schiller’s ode, “joy” is understood to be a kind of initial engine that, as a “powerful spring,” drives the wheels, entices flowers from their seeds and suns, yes indeed, suns plural, from the firmament (heavens). Goethe, a contemporary of Schiller, explored the concept of joy in his poem “Joy”, however, he emphasizes above all its fleeting nature, and warns against trying to catch hold of and “dissect” it.

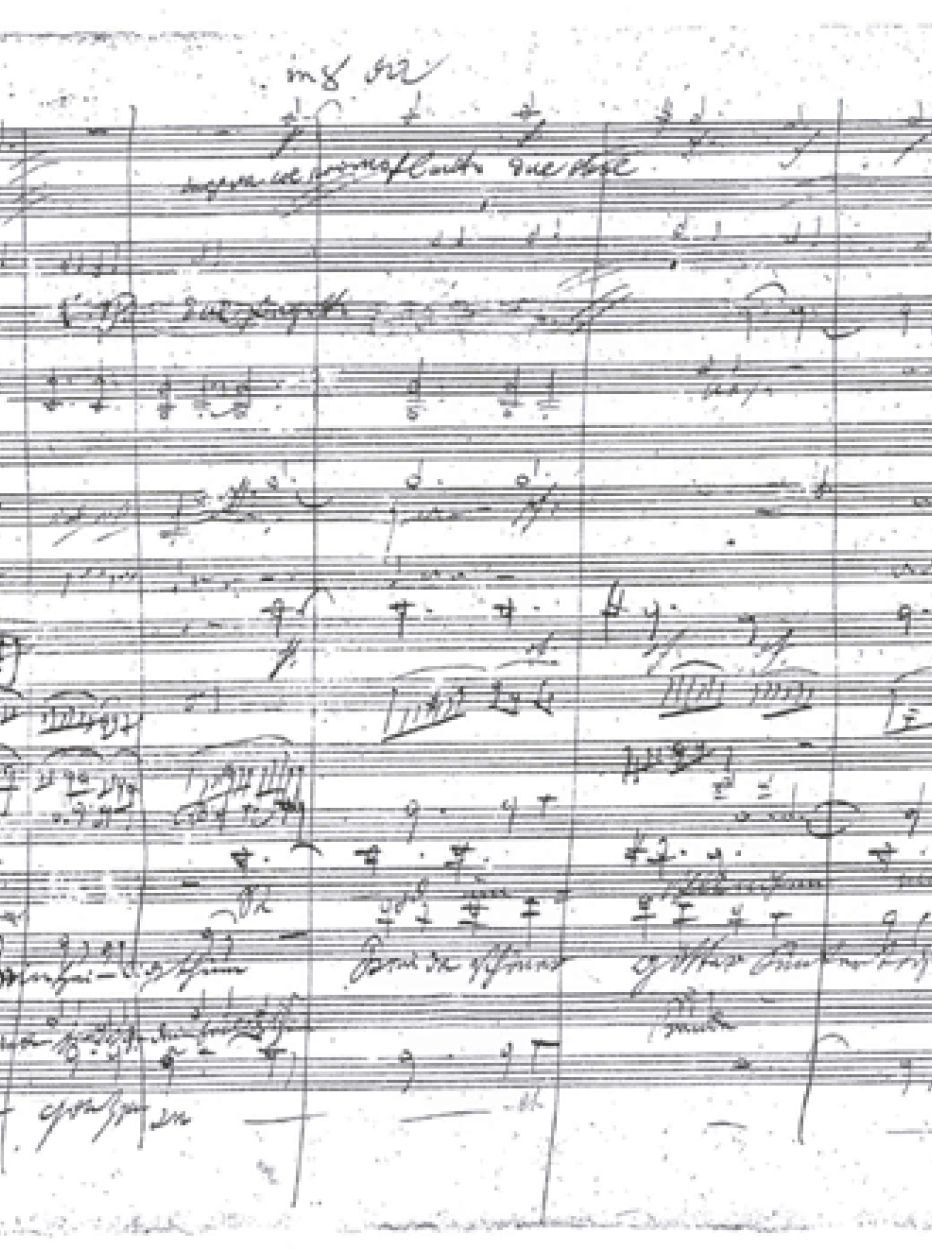

Beethovens Neunte: Handwritten page from the fourth movement of

Ludwig van Beethoven's “Ninth Symphony”. The fourth movement, in which the choir recites the text of Friedrich Schiller's poem "To Joy", is known as "Ode to Joy".

Goethe-Schiller-Denkmal

Joy as a philosophy of life already existed long before Beethoven, Goethe and Schiller. In the fourth century BC, the Greek thinker Epicurus invented a kind of guide to happiness. He regarded joy as the highest objective of his philosophizing.

Gemälde von Goethe und Schiller: Der Weimarer Musenhof, oil painting by Theobald von Oer 1860: Schiller reading in Tiefurter Park. Among the audience is also Goethe (standing on the right).

Joy, he wrote in a letter to Menoeceus, is the “alpha and omega of a happy life” and “joy is our first and kindred good, it is the starting point of every choice and of every aversion, and to it we come back, inasmuch as we make feeling the rule by which to judge of every good thing.”

The concept of happiness is interchangeable with joy, and the Founding Fathers of the United States defined this striving towards it as a basic right, alongside life and freedom, that was to be protected by the state.

The idea of joy being innately human is something with which even modern-day scientists would agree. Admittedly, they appear almost sober by comparison with the enthusiasm displayed by Schiller and Beethoven when in the dictionary of psychology (published by Spektrum-Verlag) they describe joy as a sensation that “contributes to alleviating life.” Yet the same definition also talks of joy being a “primary emotion,” that is to say a feeling that, much like fear or surprise, is deemed an integral part of any human existence – and this holds true for all of the world’s cultures.

Two renowned religious leaders of late have highlighted the relevance of joy across denominative boundaries: Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu from South Africa and the Dalai Lama, the Buddhist spiritual leader. They met in 2015 to talk about happiness and joy – only to discover how similar their views were (as recorded in “The Book of Joy” published in 2016). Whether it means being modest and thankful, sympathizing and forgiving, allowing humor into one’s life or adopting at times a different perspective – in their understanding of how joy comes about, they did not disagree much despite their different backgrounds.

Above all, however, they are united by their conviction that the greatest source of joy lies in relationships with other people. This does not require one to join any religious group – even if this is precisely what gives both spiritual leaders a great deal of joy – as good bonds with friends or family members can also give rise to joy. They appeal for people to reject the self-centeredness that is typical of modern times and open themselves up to those around them.

Most importantly, they should turn to others who are worse off than themselves and address their suffering with “the laughter-filled, tear-stained eyes of the heart.” This turning to other people, according to the Archbishop and the Dalai Lama, is the true secret of joy: all men become brothers, or, in the 21st century, all human beings become brothers and sisters.

Written by Guest Contributor: Fareed Majari, Director of Goethe-Institut Gulf Region.