The Rain of Light

Image: Rain of Light’ ©Department of Culture and Tourism - Abu Dhabi. Courtesy Louvre Abu Dhabi.

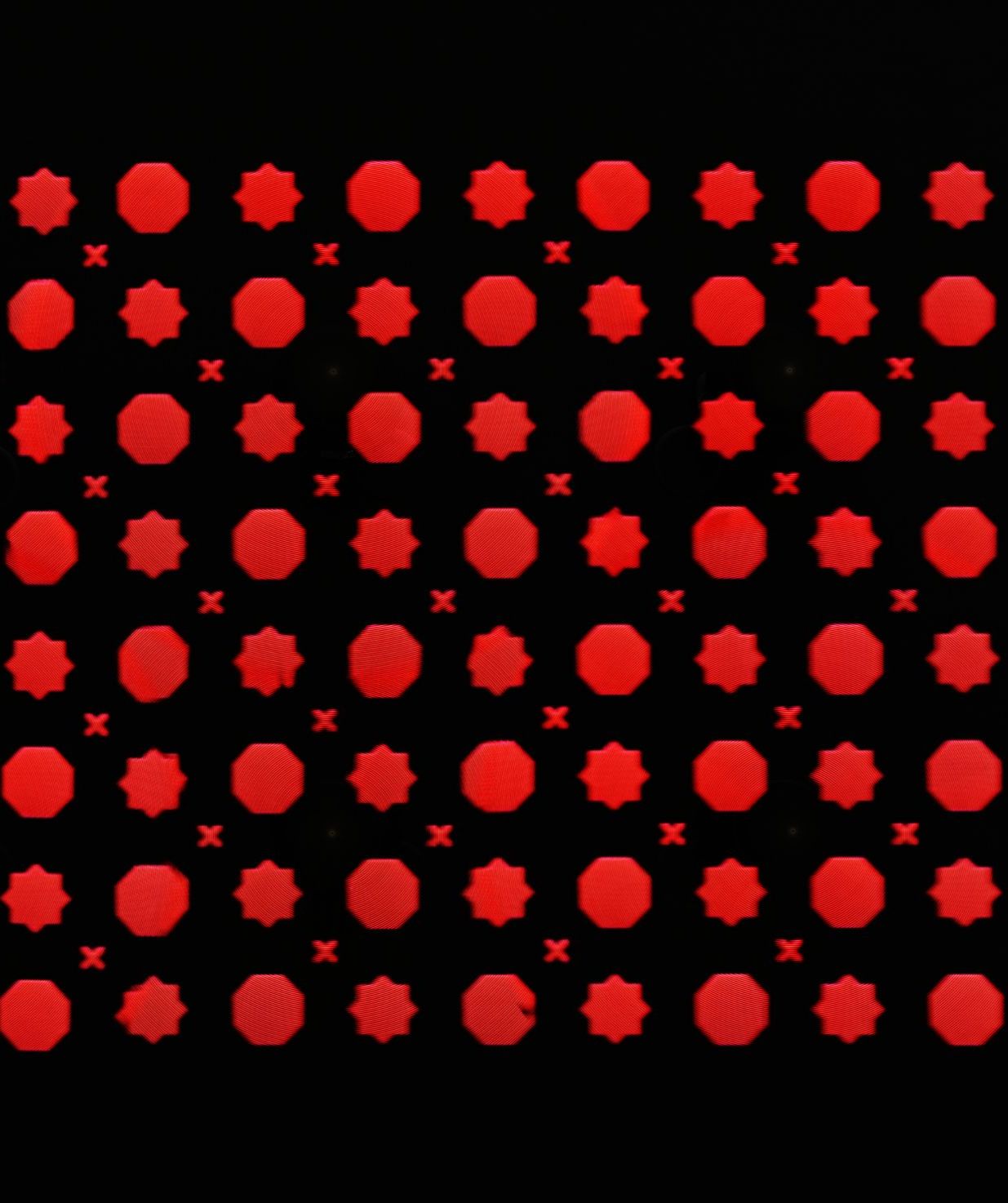

The centrepiece of Jean Nouvel is a huge silvery dome that appears to float above the museum-city. Despite its apparent weightlessness, the dome weighs around 7,500 tonnes (similar to the Eiffel Tower in Paris).

Inspired by the cupola, a distinctive feature in Arabic architecture, Nouvel’s dome is a complex, geometric structure of 7,850 stars. These stars are repeated at various sizes and angles in eight different layers.

As the sun passes above, its light filters through the perforations in the dome to create an enchanting effect within the museum, known as the ‘rain of light'. This tribute to nature is inspired by the palm trees of Abu Dhabi. Their leaves filter and soften the bright sunlight from above to project a dappled pattern on the ground.Image: Rain of Light’ ©Department of Culture and Tourism - Abu Dhabi. Courtesy Louvre Abu Dhabi

Associated with prophecy and spirituality, light has been regarded since Antiquity as a visible manifestation of invisible powers. This universal metaphor is shared by the great philosophies and religions, which place it at the centre of sacred space, where it is perceived as a physical phenomenon endowed with an infinite spectrum of metaphorical religious images. In the culture of ancient Egypt, light was considered to accompany the original cosmic dawn.

Light was therefore life and countered the darkness of death. These elements are captured in Wing 2, Gallery 4 – The Universal Religions at the Louvre Abu Dhabi. At the origins of Hinduism, the Indian theology of the Rigveda regarded the divine creator Prajapati as a primordial sound exploding into countless gleams of light, creatures of harmony, while the founder of Buddhism was given the sacred title of the Buddha, the Enlightened One.

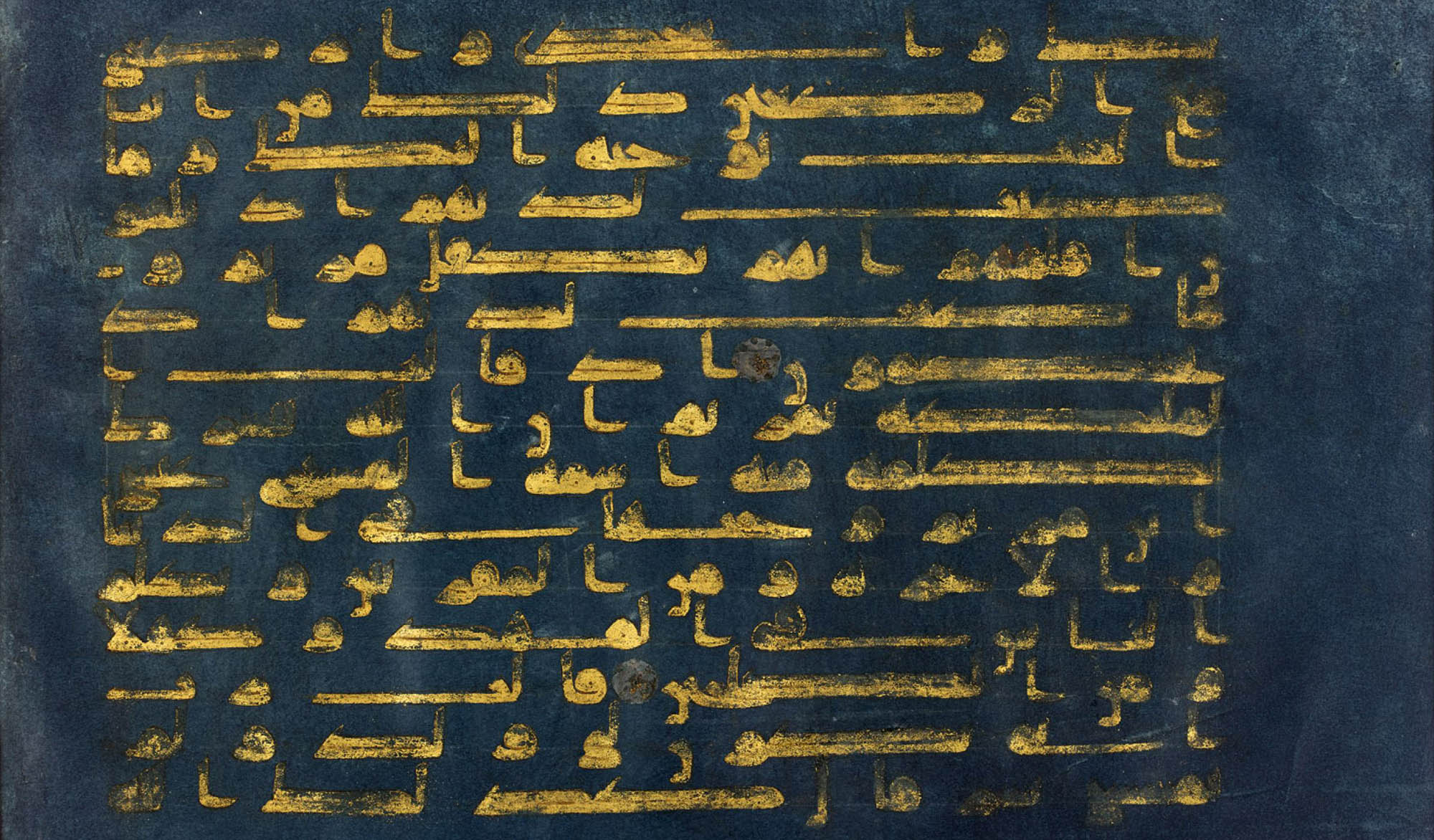

Page of the “Blue Quran” North Africa c. 900 H. 29.8, W. 34.6 cm; gold on dyed parchment©Department of Culture and Tourism - Abu Dhabi. Photo by APF. Courtesy of AD Louvre Museum

Unlike the pantheistic civilisations, which identify light with divinity itself, the Abrahamic religions see light as a symbol of the revelation and transcendence of God. In the biblical Old Testament, the first act of creation is the separation of light and darkness (Genesis, 1:3). In different ways, this metaphysical bond with light has informed the choice of new architectural designs, techniques and materials. A direct and impalpable expression of the divine in Islam, light is sanctified in the Al-Nur surah of the Quran (24:35), while in the West, the pursuit of large spaces, combined with the use of various metals, gave birth to the transparent chromatic art of stained glass.

Particular importance is attached to light (al-Nur) in the Islamic world as one of the ninety-nine names of Allah and the subject of surah 24 of the Quran. Before he was chosen as the messenger of God, the prophet Muhammad was in the habit of seeking seclusion and meditation on Jabal Al-Nur, the mountain of light, near Mecca, where he received his first revelation from God through the Archangel Gabriel in Hira cave.

“Allah is the light of the heavens and the earth. A parable of His light is a niche wherein is a lamp; the lamp is in a glass, the glass as it were a glittering star,” (Qur’an 24:35). This verse from the Quran is frequently inscribed calligraphically on mosque lamps, where form is transcended by the word. In Christian theology, the vertical perception of light had a crucial influence on religious art and architecture, the basic principle of which associates the divine with natural light as opposed to darkness.

This was expressed, in particular, through the new architectural techniques of the Gothic period, which made it possible to transform places of worship into authentic cathedrals of light, like the Basilica of Saint-Denis near Paris, conceived in the 12th century by Abbot Sugar as an earthly representation of the heavenly Jerusalem. The stained-glass windows incorporated in the facades of cathedrals transform physical light into divine radiance, flooding the interior and shining on the congregation. The art of stained glass reached its peak in the 13th and 14th centuries with the windows of such places as the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris and the cathedrals of Reims and Regensburg.

One object that captures the essence of light, beauty and great depth is a page of the famous ‘Blue Quran.’This page is from the one of the most sumptuous ancient copies of the Quran to have survived to the present day. Consisting of seven volumes, it was probably produced in Kairouan, Tunisia, in the 9th or 10th century. The apparent simplicity of kufic calligraphy and the balance of the composition make it a work of great purity cadenced by the contrast between the gold and the midnight-blue background coloured with indigo. The idea of colouring was borrowed from the Byzantine imperial codices. The dark blue symbolises the celestial universe and the gilded letters the divine light spread by the word of God