Orhan Pamuk on the Art of Writing

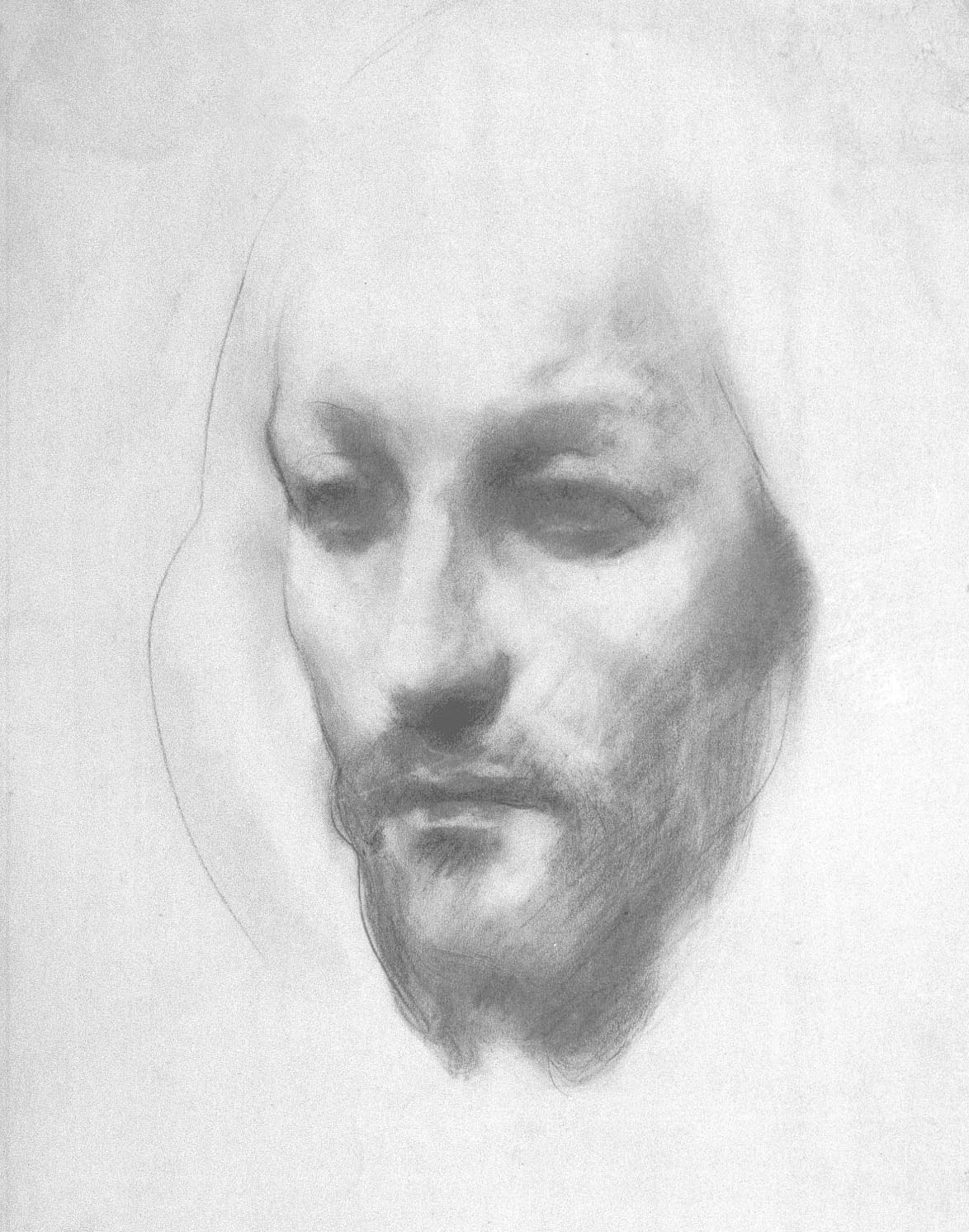

Author Orhan Pamuk

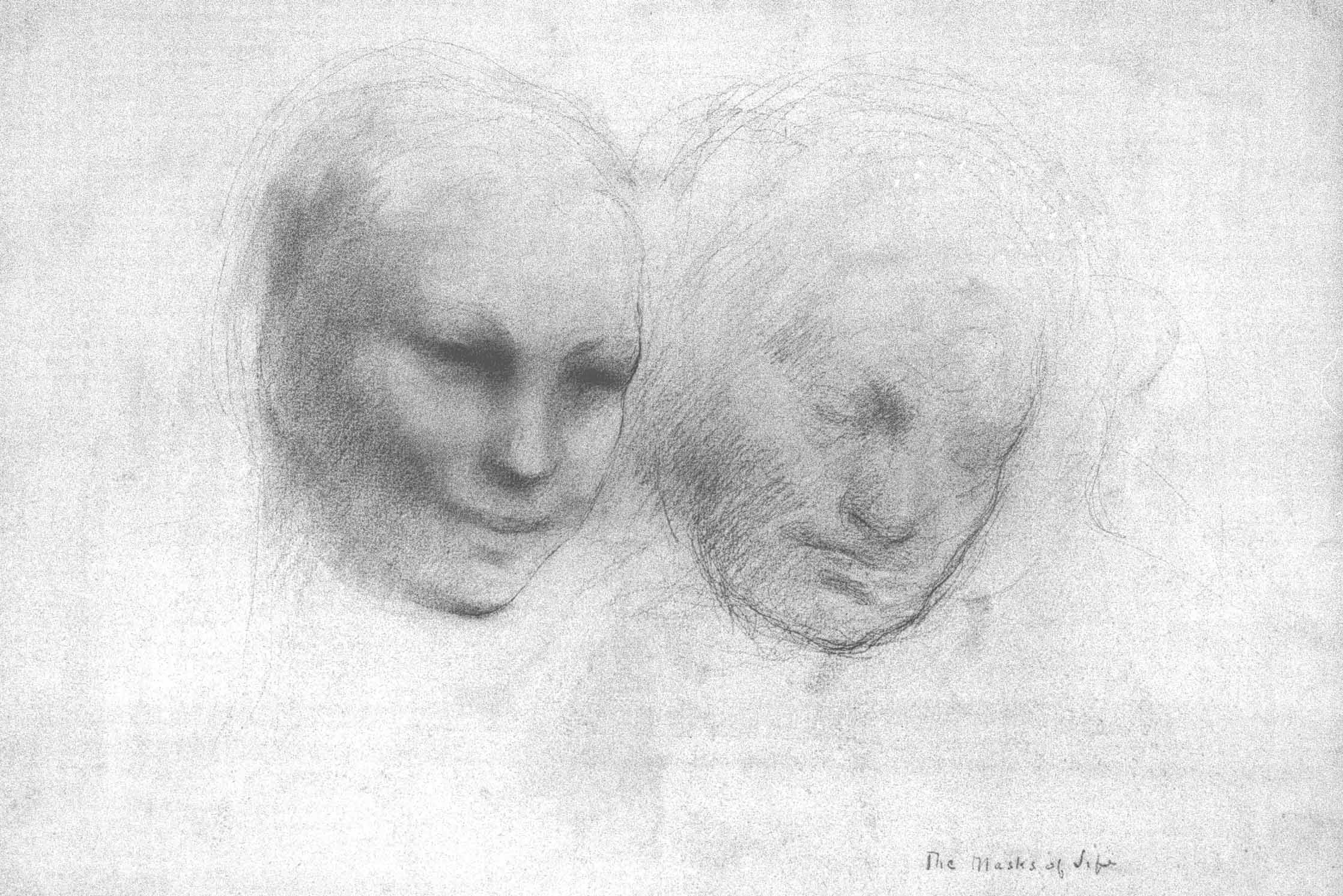

Orhan Pamuk at Ithra giving a speech on writing.

What can one say when one meets the honorable Orhan Pamuk? He is one of the literary world’s brightest and most profound of writers, sharp, complex, one who truly embodies the definition of a writer, a true master of words. A humble writer like myself was in awe of him, and paid close atten-tion to every word uttered —each treasured—a possible sneak peek into the mind of this great writ-er.

With over 13 million books sold in 63 languages, the multi award winner has been writing for the last 47 years and will continue to do so as writing is more than what he does, it is who he is. In 2006, the Turkish writer received the Nobel Prize for Literature, making him the second youngest person to receive the award in its history. It was awarded to Mr. Pamuk “who in the quest for the melancholic soul of his native city has discovered new symbols for the clash and interlacing of cultures."

The youngest laureate was Rudyard Kipling, who was 41 years old when he was awarded in 1907.

Mr. Pamuk was at Ithra in Dhahran for the final ceremony of the seventh Reading Enrichment Pro-gram (iRead), a celebration of reading and readers. It was his first ever trip to Saudi Arabia. He seemed to like the Saudi traditional coffee (Qahwa), where he drank at least four cups of it as it was poured out of a traditional coffee pot (Dallah) and into a small traditional coffee cup (fenjan). While sitting with him, he mentioned how he liked Ithra’s majestic building, and he commented on the state of the literary world such as the reduction of the printed version due to high costs, and the overall negative impact a high cost of living has on the abilities of readers to buy books and the rise of digital books and its readership.

Ultimately, he was in his element whenever he spoke about his home country of Turkey, the evolution of the Turkish language, and mentioned how he doesn’t really watch TV but heard how the Turkish soap operas are popular amongst the Arab viewers.

But these are just small snippets, it was his speech that was in many ways historic, a testament to a lifetime of writing, and a gift to writers and his readers.

This speech is a must read for every writer at whatever stage in their career.

“This year I am seventy years old. I am writing novels since the last 47 years. I started in Istanbul when I was twenty three…Today I want to make some general remarks about being a writer for so many years. My comments will be against the clichés of being a writer. Most common of these re-ceived ideas about being a writer is inspiration.

Yes, inspiration is essential, but the writer’s most important secret is not inspiration – for it is never clear where the inspiration comes from. More important is a writers’ stubbornness, his patience.

Today I am more proud of my determination to write than my talents though I am also talented, I think. That lovely Turkish saying – ‘to dig a well with a needle’ – seems to me to have been said with writers in mind. In the old stories, I love the patience of Ferhat, who digs through mountains for his love – and I understand it too.

In my novel, My Name is Red, when I wrote about the old Persian miniaturists who had drawn the same horse with the same passion for so many years, memorizing each stroke, that they could recre-ate that beautiful horse even with their eyes closed, I knew I was talking about the writing profession, and my own life.

Another subject is hope. To be strong against all kinds of horrors and injustice. If a writer is to tell his own story – tell it slowly, and as if it were a story about other people – if he is to feel the power of the story rise up inside him, if he is to sit down at a table and patiently give himself over to this art – this craft – he must first have been given some hope. The angel of inspiration (who pays regular visits to some and rarely calls on others) favors the hopeful and the confident, and it is when a writer feels most lonely, when he feels most doubtful about his efforts, his dreams, and the value of his writing – when he thinks his story is only his story – it is at such moments that the angel chooses to reveal to him stories, images and dreams that will draw out the world he wishes to build.

If I think back on the books to which I have devoted my entire life, I am most surprised by those mo-ments when I have felt as if the sentences, dreams, and pages that have made me so ecstatically hap-py have not come from my own imagination – that another power has found them and generously presented them to me.

A writer talks of things that everyone knows but does not know they know. To explore this knowledge, and to watch it grow, is a pleasurable thing; the reader is visiting a world at once familiar and miraculous. When a writer shuts himself up in a room for years on end to hone his craft – to cre-ate a world – if he uses his secret wounds as his starting point, he is, whether he knows it or not, put-ting a great faith in humanity. This is the second important secret of the writer I think. To believe in a common humanity. My confidence comes from the belief that all human beings resemble each other, that others carry wounds like mine – that they will therefore understand. All true literature rises from this childish, hopeful certainty that all people resemble each other. When a writer shuts himself up in a room for years on end, with this gesture he suggests a single humanity, a world with-out a center.

On the other hand, it is hard to believe that our lives resemble the lives of other people in the world. There is something in our petty worlds that deny universality. In my books I have described in some detail how this basic fact evoked a Checkovian sense of provinciality, and how, by another route, it led to my questioning my authenticity.

I know from experience that the great majority of people on this earth live with these same feelings, and that many suffer from an even deeper sense of insufficiency, lack of security and sense of degra-dation, than I do.

But today our televisions and newspapers tell us about these fundamental problems more quickly and more simply than literature can ever do. What literature needs most to tell and investigate today are humanity’s basic fears: the fear of being left outside, and the fear of counting for nothing, the strong anxiety of not being important and the feelings of worthlessness that come with such fears.

I always think about the collective humiliations, vulnerabilities, slights, grievances, sensitivities, and imagined insults, and the nationalist boasts and inflations that are their next of kind. I spent forty seven years thinking about these anxieties and expressed them in my work in different forms and different stories. Whenever I am confronted by such sentiments, and by the irrational, overstated language in which they are usually expressed, I know they touch on a darkness inside me. We have often witnessed peoples, societies and nations outside the Western world – and I can identify with them easily – succumbing to fears that sometimes lead them to commit stupidities, all because of their fears of humiliation and their sensitivities.

I also know that in the West – a world with which I can identify with the same ease – nations and peoples taking an excessive pride in their wealth, and in their having brought us the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, and Modernism, have, from time to time, succumbed to a self-satisfaction that is al-most as stupid.

There are many reasons to write. But once we shut ourselves away, we soon discover that we are not as alone as we thought. We are in the company of the words of those who came before us, of other people’s stories, other people’s books, other people’s words, the thing we call tradition.

I believe literature to be the most valuable hoard that humanity has gathered in its quest to un-derstand itself. Societies, tribes, and peoples grow more intelligent, richer, and more advanced as they pay attention to the troubled words of their authors, and, as we all know, the burning of books and the denigration of writers are both signals that dark and improvident times are upon us. But lit-erature is never just a national concern. The writer who shuts himself up in a room and first goes on a journey inside himself will, over the years, discover literature’s eternal rule: he must have the artistry to tell his own stories as if they were other people’s stories, and to tell other people’s sto-ries as if they were his own, for this is what literature is. But we must first travel through other people’s stories and books.

I want to finish my words with what I said fifteen years ago in a speech and repeated it so many times. As you know, the question we writers are asked most often, the favorite question, is; why do you write?

I write because I have an innate need to write!

I write because I can’t do normal work like other people.

I write because I want to read books like the ones I write.

I write because I am angry at all of you, angry at everyone.

I write because I love sitting in a room all day writing.

I write because I can only partake in real life by changing it.

I write because I want others, all of us, the whole world, to know what sort of life we lived, and con-tinue to live, in Istanbul, in Turkey.

I write because I love the smell of paper, pen, and ink.

I write because I believe in literature, in the art of the novel, more than I believe in anything else.

I write because it is a habit, a passion.

I write because I am writing for the last 47 years.

I write because I am afraid of being forgotten.

I write because I like the glory and interest that writing brings.

I write to be alone.

Perhaps I write because I hope to understand why I am so very, very angry at all of you, so very, very angry at everyone.

I write because I like to be read.

I write because once I have begun a novel, an essay, a page, I want to finish it.

I write because everyone expects me to write.

I write because I have a childish belief in the immortality of libraries, and in the way my books sit on the shelf.

I write because it is exciting to turn all of life’s beauties and riches into words.

I write not to tell a story, but to compose a story.

I write because I wish to escape from the foreboding that there is a place I must go but – just as in a dream – I can’t quite get there.

I write because I have never managed to be happy.

I write to be happy…”

Orhan Pamuk was born in Istanbul in 1952 and grew up in a large family similar to those which he describes in his novels Cevdet Bey and His Sons and The Black Book, in the wealthy westernized dis-trict of Nisantasi. As he writes in his autobiographical book Istanbul, from his childhood until the age of 22 he devoted himself largely to painting and dreamed of becoming an artist. After graduating from the secular American Robert College in Istanbul, he studied architecture at Istanbul Technical University for three years, but abandoned the course when he gave up his ambition to become an architect and artist. He went on to graduate in journalism from Istanbul University, but never worked as a journalist. At the age of 23, Pamuk decided to become a novelist, and giving up everything else, retreated into his flat and began to write.

Orhan Pamuk is the author of many books including My Name Is Red, Snow, The Museum of Inno-cence, The White Castle, and The Red-Haired Woman.

Orhan Pamuk's books have sold over 13 million books in 63 languages, including Georgian, Malayan, Czech, Danish, Japanese, Catalan, as well as English, German and French. Pamuk has been awarded The Peace Prize in 2005, considered the most prestigious award in Germany in the field of culture. In 2005, Pamuk was honored with the Richarda Huck Prize, awarded every three years since 1978 to personalities who "think independently and act bravely." In the same year, he was named among world's 100 intellectuals by Prospect magazine.

In 2006, TIME magazine chose him as one of the 100 most influential persons of the world. Pamuk is an honorary member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and holds an honorary doctorate from Tilburg University. He is an honorary member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters as well as the Chinese Academy for Social Sciences. In 2006, the Turkish writer received the Nobel Prize for Literature, making him the second youngest person to receive the award in its history.