The Art of Making an Idea

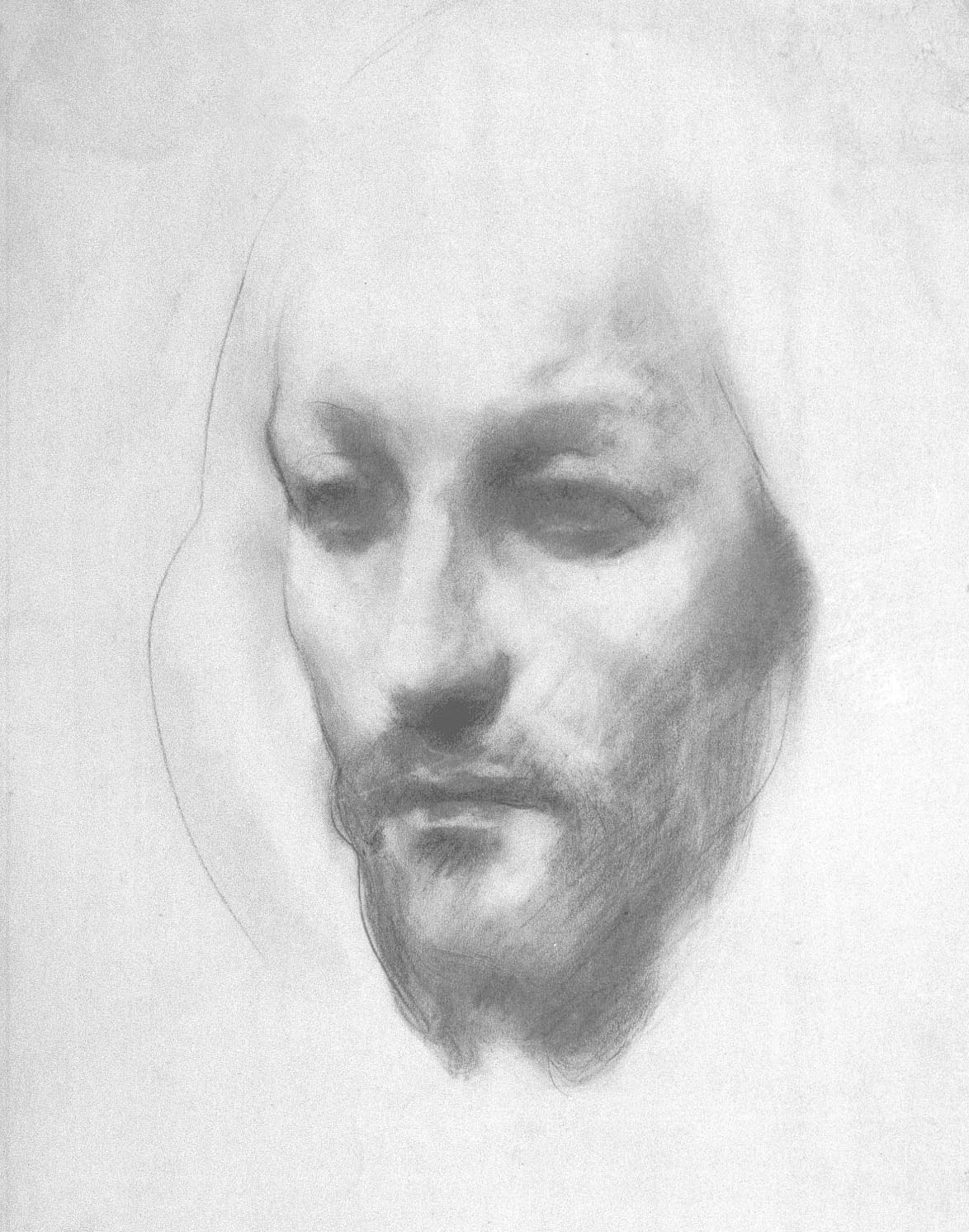

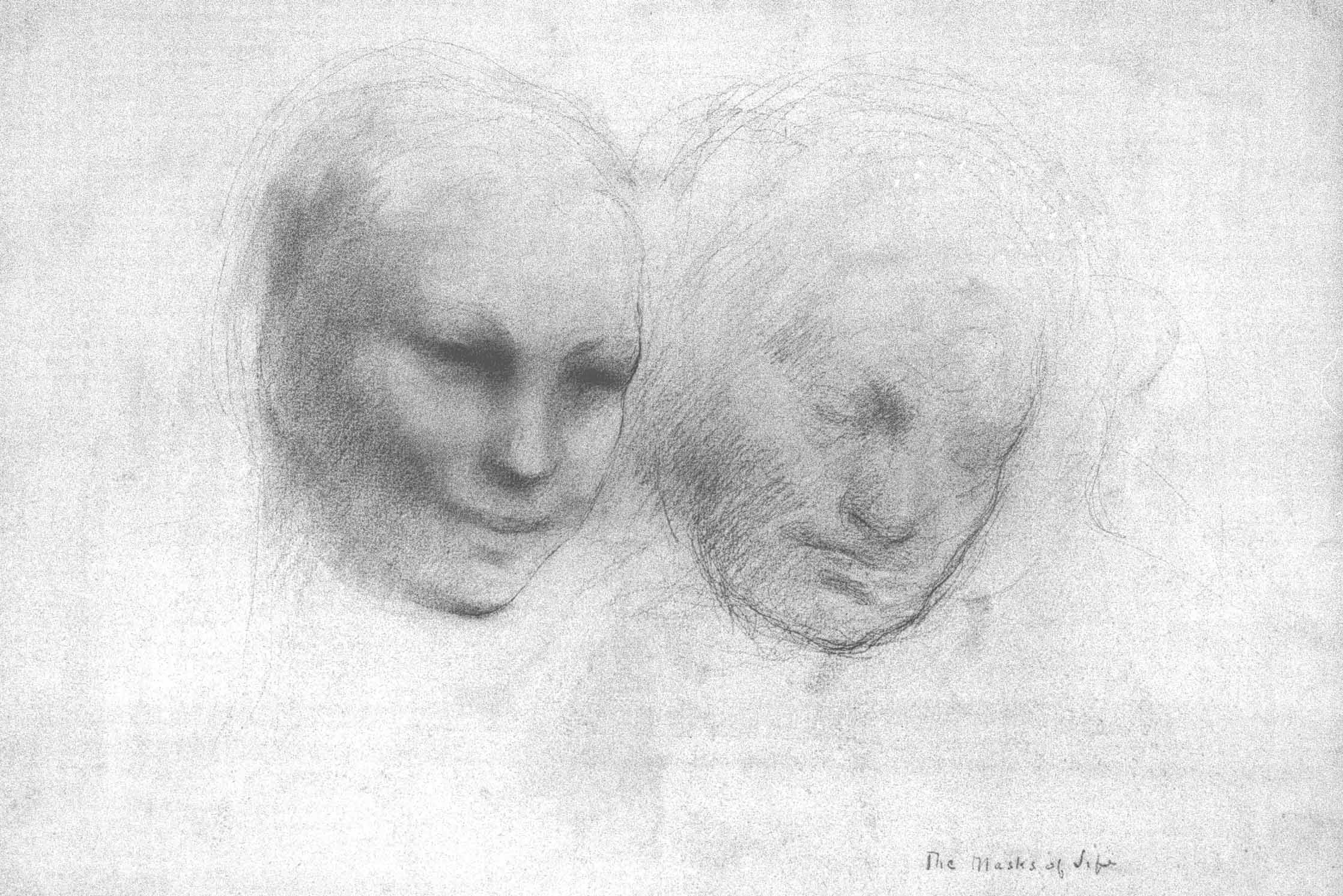

Ithra’s sketch, Tanween 2021, by the artist*, courtesy of Ithra.

Said Robert Frith

The blank page, the clean white expanse of a canvas, is a terrifying place to start a project. It is such a pure concept to have just an only white space; it takes some confidence to put another idea in its place. So, we sketch! The rough outlines of an idea began to replace the void. We illustrate the pictures in our minds or begin to map out the subject in front of us.

With a sketch, we don't have to be definite. We can erase it and start again. We can be confident with a sketch because it can be changed or removed, but is not rigid or fixed. The history of art and design is rich with great stories about sketching. The stories of these drawings give us that first connection to an idea and the mind of its creator.

Ithra’s sketch, Tanween 2021, by the artist*, courtesy of Ithra.

A great example is the story of Philippe Starck's Juicy Salif, which has been called "the most controversial lemon squeezer of the century." While squeezing lemon over his calamari dinner, Starck sketched out numerous squid-like shapes on his paper placemat. He then sent this to the Italian manufacturer Alessi. Made 3D, it has sold millions, and the controversy is that it is terrible at squeezing lemons but remains a conversation starter to this day.

The Juicy Salif is a sketch made in 3D, but you can sketch in 3D. One of the greatest proponents of this is architect Frank Gehry, famed for buildings such as the Guggenheim Bilbao and Walt Disney Concert Hall. His models for his buildings are a mass of cardboard and tape. Famously he tears, adds, and replaces elements continuously, using them as a 3D sketch for his ideas which can be seen directly in the realized crazy mass of forms that make up many of his buildings.

Ithra’s sketch, Tanween 2021, by the artist*, courtesy of Ithra.

We rarely see the 'making of an idea,' but a sketch gives us that. Using x-rays to scan the canvases of masters allows us to see the multiple variations they underwent before rendering in oil paint. Seeing the different compositions an artist explores gives us insight into the concepts they were studying and the negotiations they had with themselves. Controversially, these sketches could provide insight into how the artists saw their subjects. The Hockney–Falco thesis is a theory advanced by artist David Hockney and physicist Charles M. Falco.

Both claimed that advances in realism and accuracy in the history of Western art since the Renaissance were primarily the result of optical instruments such as the camera obscura, camera lucida, and curved mirrors, rather than solely due to the development of artistic technique and skill. In a 2001 book, Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters, Hockney analyzed the work of the Old Masters through their sketches and argued that the level of accuracy represented in their work is impossible to create by "eyeballing it."

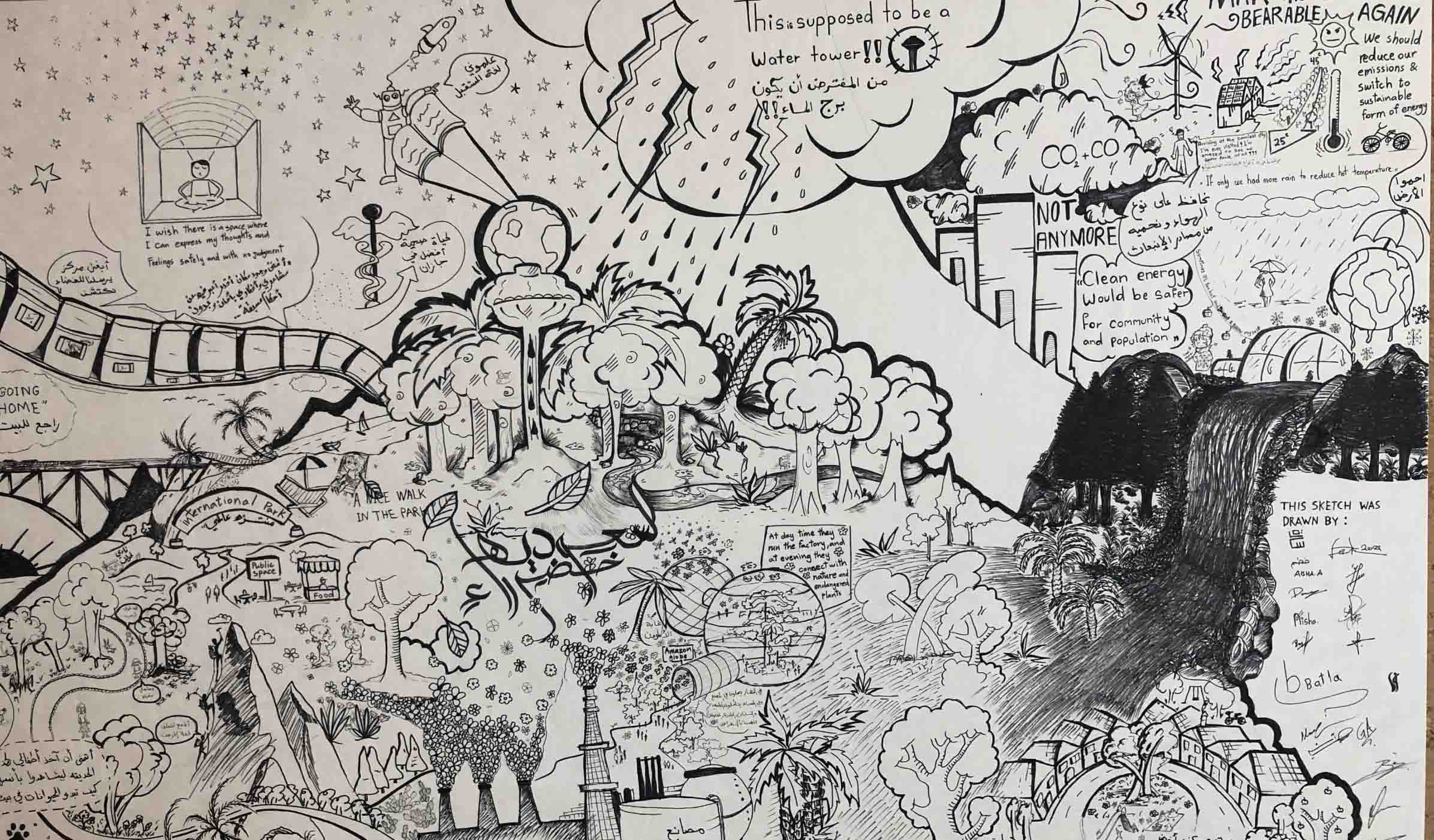

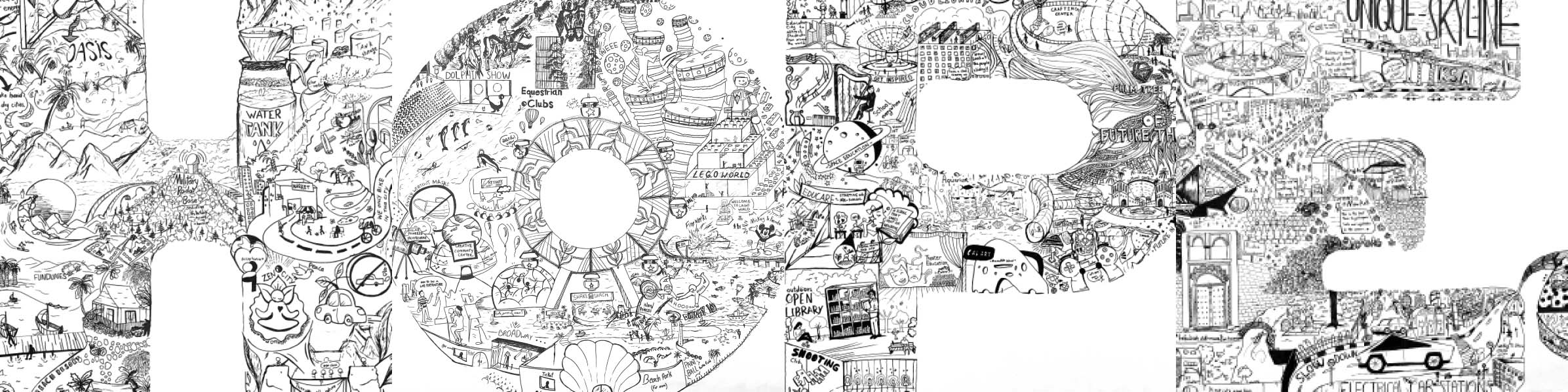

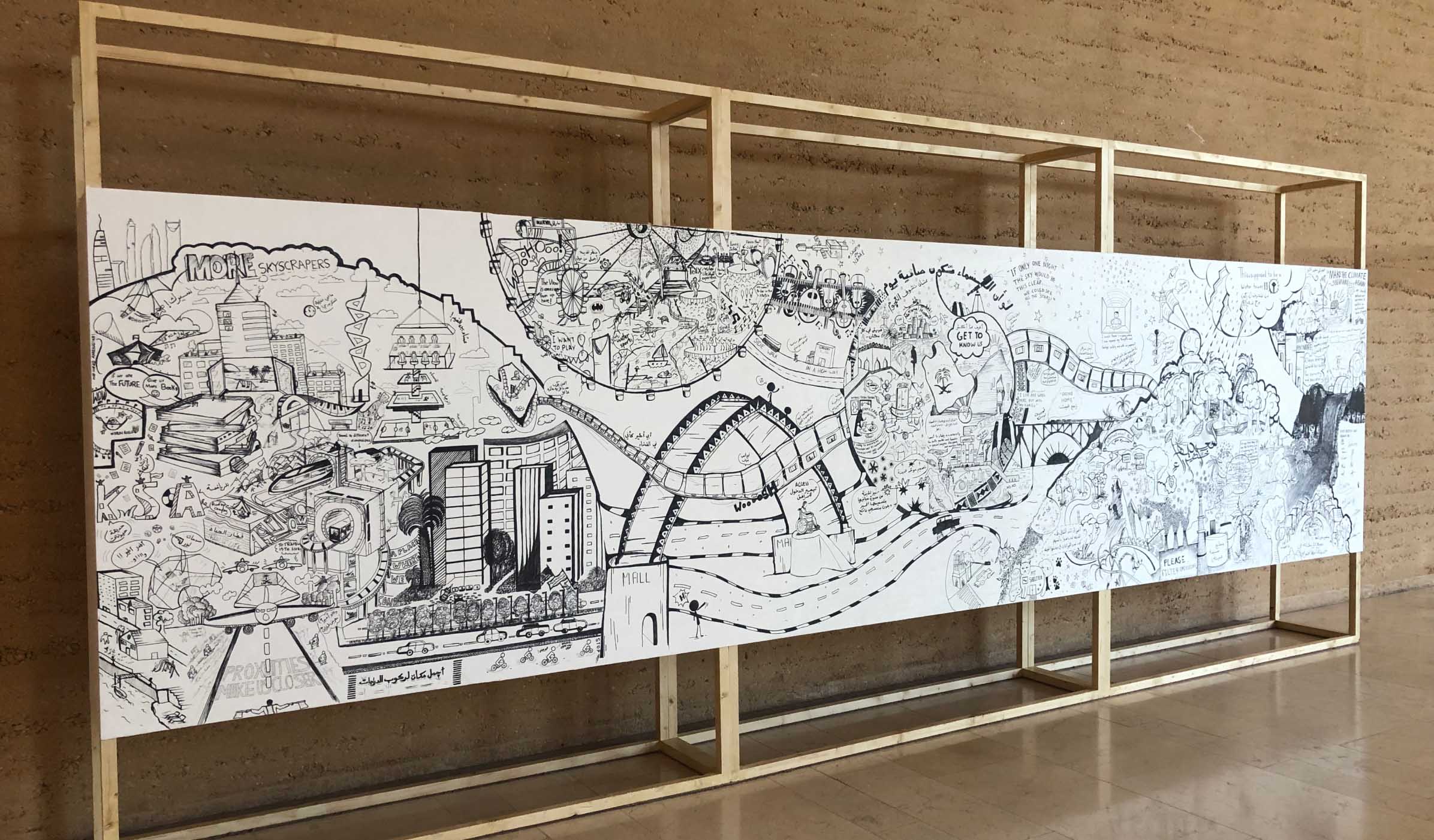

Analogia Project by Andrea Mancuso and Emilia Serra. Courtesy of Ithra.

Analogia Project by Andrea Mancuso and Emilia Serra. Courtesy of Ithra.

Analogia Project by Andrea Mancuso and Emilia Serra. Courtesy of Ithra.

The underlying sketching technique indicated they moved from the multiple lines created when mapping out an image to a continuous line used when tracing an image.

Therefore, they were beginning to use optics as an aid to see their subjects. The art of sketching is just as much about training yourself to look as it is to draw. Perhaps that is what sketching will teach is mostly to '...look twice, draw once.’

*The artists: Serei Alghadban, Faisal Al-tayeb, Sara Aljoughiman, Badrya Abdurahman, Batla Al-Otaibi, Aisha Al-maghlouth, Fatma Alluwaim, Danah Alotaibi, Aisha Alghareeb, Nawaf Al-Dossari . Courtesy of Ithra.