Divine Calls to Prayer

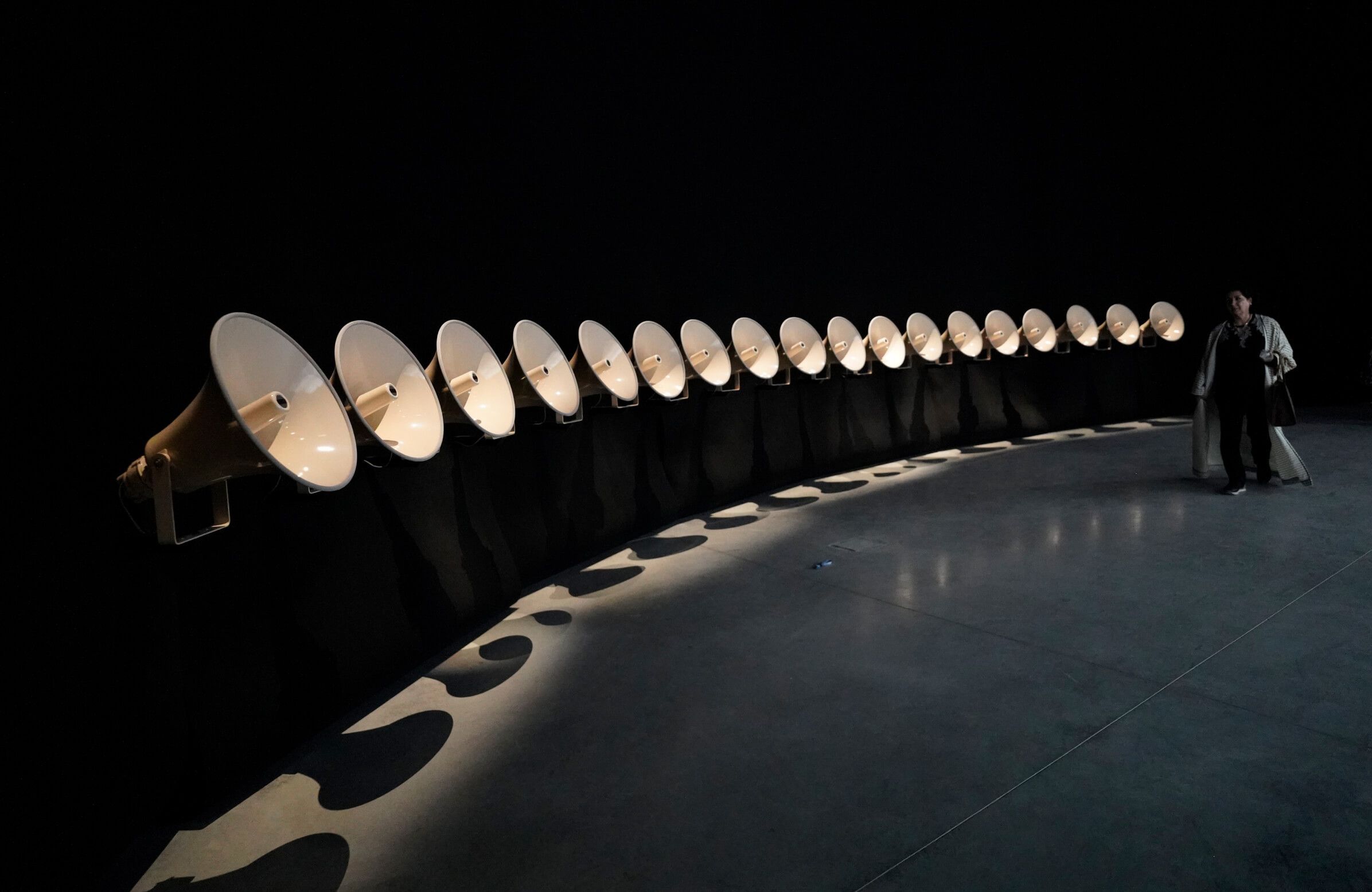

Cosmic Breath by Joe Namy.

Sound art is a form of contemporary art that is becoming today’s hottest emotive medium. Using sound as a channel for creative expression is the most direct way for viewers to engage with art as sound can affect your emotions immediately, without any thought or explanation. Sound art is not only an aural experience, as some artists use sound by bridging and crossing barriers between environmental and other non-musical sounds, and music in a contemporary or historical sense. Others investigate the political and cultural implications of certain sounds.

The first Islamic Arts Biennale is taking place at the iconic Hajj terminal in Jeddah (from January 23 to April 23, 2023) under the theme of Awwal Bayt. Joe Namy’s Cosmic Breath triggered our imagination and memories and touched us deep to the core, putting us right in the middle of the environment these calls of prayer are from. This work is an 18-channel sound installation of prayer recordings from 18 points around the globe.

This immersive installation features collected recordings of the adhan from distant places and time. Within this constant there are a multitude of variations. The audio includes what is considered to be the first recording of the adhan, from the Haram Mosque in Makkah from the late 1800s, and the earliest recording from the Magindanas in the Philippines. These different locations add unique sound textures that evoke their environment and community. The work is designed for each voice to be heard both individually and simultaneously with the others.

Joe Namy is a media artist, composer and educator (born in 1978 in Michigan, USA) who lives and works between Beirut and London. His practice often addresses identity, memory and power structures embedded in sound and music. He works collaboratively across mediums in sound, performance, sculpture, and video. Joe received a MA from New York University, and his work has been exhibited, screened and amplified at the Detroit Science Center (USA), Queens Museum (USA) , Brooklyn Museum (USA) and Beirut Art Center (Lebanon).

Cosmic Breath by Joe Namy.

Q1- what was the inspiration behind the work?

I'm really interested in sound landmarks and sound in public spaces, and the role of sound in spirituality. Cosmic Breath came out of a conversation with the curator of the biennale , Sumayya Vally, as she pointed out how at every second of the day there is an adhan happening somewhere on Earth. And despite the fact that each adhan is reciting the exact same phrase, there are infinite variations within this constant. But not only is each adhan recited uniquely, our reception is also affected by the conditions and situations that are happening when we hear the call, the environmental ambience from where the call is amplified, in the city amidst the cacophony of bustling traffic.

Q2- what was your process in creating this artwork?

I wanted to highlight places and situations, both historically and geographically, where social conditions might create new and unexpected reflections on the adhan. I collected over 100 recordings of the call – some were archival recordings, while others we worked with local sound engineers to record the adhan and the ambience of specific locations around the world. Once we gathered all the recordings we tried to select those that resonated most with the project. So for instance it was important to include the first ever recording made of the adhan, from 1885 at the Haram Mosque in Makkah, which was recorded on wax cylinder. It was also important to include a recording from Masjid Sultan in Singapore, which is considered to be the first mosque to use loudspeakers to amplify the adhan in the 1930s. There are also recordings from other distant places like from a forest in Kaga Japan or a street corner in Hamtramck, Michigan, USA.

In thinking about how to install the audio in the gallery space, I wanted to visually focus on the materiality and technology used to amplify the adhan. So I looked into the kinds of loudspeakers that mosques used most often and how they are installed. In the end I decided on using large diameter horn speakers, each one a half meter wide. These were placed side by side and at a height that would allow for a more intimate and personal experience for the listener, so that people can stand over them, listen to them up close, and feel their presence. These speakers are almost always placed high up, atop minarets or on rooftops, to maximize the projected area of amplification. So it was important to have people come in close contact with them to create a uniquely personal listening space.

Q3- what is the role the sound plays in your piece and how do you feel the sound affects the viewers?

The installation includes 18 channels, and is designed so that each recording plays from its own speaker. It’s mixed for each voice to be heard both individually and simultaneously with the others as a whole. Because of how the speakers are arranged, in an arc over an area of nine meters, people can step back and hear them all together, or come up close and walk along the speakers to hear each one individually, creating different listening experiences.

It was also important to leave in the ambience and environmental sounds; these are not just voice only but include the sounds of the city, the forest, the sea, or the crackle of the archival wax cylinder – all the different sound textures that evoke their environment and community.

Cosmic Breath by Joe Namy.

Q1. What does art mean to you?

As a social artist, I'm especially interested in how art can bring people together in new ways, how it can speak to our history, our memories, our subconscious, while also grounding us in the present and allowing us to imagine alternative futures.

Q2. Tell us about your relationship with music?

I started out playing drums when I was young, learning traditional Arabic music but also studying jazz and heavy metal. It wasn't until later in university that I transitioned to visual arts. But music has always been the root of my art practice, and coming from varied and rich musical worlds deeply informs my approach to making art, whether it’s visual or sound based. I think of music as organized noise; sound with intent. So a construction site could be music, or a car, or the wind. In my art practice, I'm mostly interested in the complexities of translation in all this - from language to language, from score to sound, from drum to dance. These are all human connections.

Q3. Tell us about yourself, when was the first musical piece you composed?

I first learned drums from my mother when I was young; she taught me to play the Arabic drum we call derbekah, or dumbek, or tabla. When I think about my earliest compositions, they were actually improvisations, rhythmic patterns that I would make up on the drum and memorize. They weren't written down. It wasn't until later, while formally studying composition in university, that I understood those early patterns were actually a form of composing. There's so many ways that one can compose. I think of that when listening to my 4 year old nephew make up songs while he plays; it's such a natural thing.

Q4. Tell us more about your art, and the themes you like to explore.

My practice is very collaborative, based in social art. It often focuses on the socio-politics of music and sound. My projects are often very research heavy and unfold over years. So one example, I'm currently working on a PHD at Oxford University that looks at the history and resonance of opera houses in the Middle East and North Africa. There's actually quite a long and rich history in the region. I'm not so much interested in the music that was performed in these theaters, it's more about the buildings themselves and their relationship to the cities and culture they are a part of.

Q5. What are some of your past projects that you feel had the most impact?

I'm currently an artist in residence for the London Borough of Barking & Dagenham, working within the government to start a community radio station. It’s where I met the IAB curator Sumayya, as part of the Serpentine Pavilion she designed in 2021; she also included 5 satellite extensions of the pavilion that would live in different locations around London. One of them was based at a public library in Dagenham, called the Becontree Broadcasting Station, which I'm setting up and running. The impact has been tremendous, as I'm working between the community and the local government, providing skill training workshops for people interested in creating radio or podcasts, and also highlighting local events and happenings. Listening communally and creating an open platform for expression and urgency.

Q6. What are some of your future plans and current projects you would like to share?

I often work on long term research projects. My opera project has been ongoing since 2017. Another project, titled Automobile, is a performance that started in 2011 in Beirut using cars with customized, souped-up sound systems. We bring around 10 or more cars together for a site-specific meet up, and hook them all up to a custom audio interface I designed that allows me to do a live surround sound mix through the car sound systems, with each car playing a separate synchronized sound, creating an immersive 10 channel sound experience with extremely bass-heavy systems. So far I've done 9 iterations of this performance in different cities around the world, in Beirut; Mannheim, Germany; Montreal and Toronto, Canada; London, UK; Gwangju, S. Korea; Abu Dhabi; and most recently in Sharjah last November. I'm currently working on the 10th version for Brussels this coming May.

Cosmic Breath by Joe Namy.

Q7. What moto do you live by?

"The waves are already waving..." is one of my favorite quotes right now by the composer Pauline Oliveros. I read it as meaning we have to tap into the current that’s around us, be more empathic with one another and sensitive to our environment, this planet, and really tune in. There's so much noise and distractions blocking us, so use whatever you can find to help you get in tune.

Q8. Any role models you want to share that inspired you?

I've been fortunate to have so many amazing role models in my trajectory as an artist. And often think of those who've paved the way for me to do what I do. I'm especially indebted to the brilliant Egyptian American composer Halim El Dabh, the godfather of African electronic music. He was a sort of mentor to me, and his approach to sound and creativity has been immensely important in my practice. His way of thinking about music and sound was so revolutionary and ahead of his time. He was credited as having invented the first piece of electronic music in 1944 in Cairo. He continued creating and innovating until he passed away in 2017. I've been fortunate to be able to access his archive over the past few years, and I'm constantly inspired and in awe going over his compositions, notes and sketches.

Q9. Any advice to young musicians?

I'm learning from them! The most important thing I would stress is the importance of community.

Q10. How did the musical landscape change in the Middle East over the past few decades? In Saudi Arabia?

This is a big question. As an artist who works with sound and performance in a mainly visual arts setting, the landscape for contemporary art has been changing so quickly. I'm not so sure that's a good thing, but it is what it is. Everything seems to be changing so fast. I don't try to look at trends, I can only do what I do, I can't be anything else but me! But I'm also so inspired by all the new music and artists. One of my favorite vices right now is binge watching drummers on TikTok. I do a monthly radio show on Radio Alhara, called rhythm x rhythm, dedicated to TikTok tablas and Arabic drumming sessions that people post. I think this is the future of music and I'm all for it.