The subject of sustainability and climate change is an important concept in art for our day and age. We look at art not just as a piece of beautiful work by a professional or amateur artist. Art has always had a message, intentional or not, and with the effect we are having on our environment, it has become a subject of discussion.

Recycling, Reduce, Reusing

Natural, Local, Organic

Upcycle, Mend, Fix

Sustainable, Clean, Green

All these terminologies have become synonymous to how we deal with sustainable practices and art. They all mean the same thing in the end: to not waste the resources we have. In art, it means to ensure the artwork is sustainable from the conceptual phase all the way to its longevity past creation. Of course, this hasn’t always been true, hence the existence of art restoration and processes attached to it. Also, it isn’t true for all artists: every person has their own sense of responsibility, which relates to their practice and reaction to the topic.

In this three-part article, we

will explore three artists and

their different approaches or

sense of connection with

sustainability.

Alif uses wood as the subject of his work and carves it into shapes and artworks. The idea is his art is made of wood and would not exist without the material’s interaction with the artist’s hands, creating a harmonious existence and a beautiful outcome.

Ahmed Angawi creates art with wood as the material recreating historical practices and preserving them for multiple generations. The sustainability of historical practices means understanding the materiality and engaging with perseveration techniques to ensure the longevity of the piece without waste.

Sara Abu Abdallah reflects on the importance of nature and memory through the preservation of the space in which growth happens. She also reconnects to the same lands and its nature through multiple ways mindfully.

‘Huyam,’ by Alif. 2020, 5cm x 18cm x 5cm, local Olive wood. Huyam: (highest level of love) could be translated to adoration, yet it doesn't give the full meaning. This is part of a spoon collection that feeds the soul.

Although he still is a multidisciplinary artist exploring calligraphy and art in different forms, Alif used to be solely a calligraffiti artist until he discovered the joy of carving wood in 2018. “I have a love for cooking and feeding the people I love.

It’s a sacred practice where you create something without any expectation of return as it disappears as soon as you place it on a plate. In that spirit, I decided to carve a spoon, one of the main utensils used to share food and, in doing so, I discovered my love for the knife and it had become a passion.” This inspired his collection Soul Nutrition, carved spoons with Arabic calligraphy inspired by his own style. It explores words that signify love in Arabic.

Artists are always inspired but they should never copy other artists, which is a distinction Alif shows in his work as he has a unique touch and sense of exploration of his work.

“Even if it was a product that I was producing, once it becomes very popular, I would stop producing in that style.” While he was giving a workshop, there was a couple that thoroughly enjoyed it and explained that they had attended multiple workshops including one by Giles Newman.

Alif was very flattered because “I have always found Giles Newman’s work inspiring and he was the one that inspired me to carve stylistic spoons.”

“I don’t have a specific motto that I live by because life is constantly changing. Humans are always looking for stability but they don’t find it.” In his work he looks for love: “If there was no love between humans, or between God and his creations, or even between me and my pieces, there would be no connection.”

“I am an artist who is insane to the point of sanity and sane to the point of insanity.”

As wood is a natural source, it has always existed, and people have been creating things with it for centuries. “It is one of the original items that humans have dealt with. Wood derives its strength and power from the earth the same way humans do by standing on the ground. It is the reason why people ensure there is wood in their home. There is a connection that is undeniable.” This connection is what helps Alif choose his piece because once he starts carving, there is no going back. “There is a saying in the woodworking world: there is no such thing as a mistake, only a smaller carving, which is similar to life. We must always build on what already exists.”

‘Hawa,’ by Alif. 2020, 17cm x 5cm x 2.5cm, Sycamore wood Hawa: another Arabic name of love which translates into: being into someone. Designing it, had in mind the hue that Hawa creates around us when we get near that special someone.

“I don’t have a specific motto that I live by because life is constantly changing. Humans are always looking for stability but they don’t find it.” In his work he looks for love: “If there was no love between humans, or between God and his creations, or even between me and my pieces, there would be no connection.”

‘As Salam,’ by Alif. 2021, 179cm x 53cm x 15cm, local Ficus (Berham) wood. As Salam (peace) is the first thing we need before all progress, before all joy, & before all art.

“Wood is a natural resource, so we need to ensure its longevity and its source. Even when already cut, we need to ensure that it isn’t part of a deforestation process. Also there are some trees that have history and so not every tree can become an artwork.” However, the creative work also takes into consideration where the piece is going to be placed and that it would go to ruin. “I choose pieces that are treated correctly and I take the placement into consideration so it can last and withstand all the elements like sunlight or rain. Also, I ensure that it has the correct finishing so that it would not be destroyed by insects or other natural processes.”

“Don’t compete” was the first sentence that popped out of Alif in reaction to the question. Competition could be healthy and amazing, however, “when you run, you won’t see the details, or you’ll fall, so take your time and you will achieve.”

‘Gharam,’ by Alif. 2020, 5cm x 17cm x 2cm, Purpleheart wood. An attempt to gather all that is related to the strong yet delicate emotion that the word gharam carries. I was satisfied when I added the strand of hair on her eye here.

Ahmad Angawi has been and always has been a champion of craftsmanship and the power of reviving traditional practices. He was exposed to art from the moment he opened his eyes, his father is an architect and his mother is an interior designer, and has been exposed to all aspects of culture. There were multiple influences including being surrounded by craftsmen and creatives in Beit Shafei in Al Balad (Jeddah Historical District) where Dr. Sami Angawi had his office and the process of his family home being built. It highlighted to him the importance of producing with your hands and eyes.

“I used to carve into my wooden school desk and creatively use my pens or broken pencils as tools. I still have these desks laying around”. This unique Saudi artist has always been fascinated with creating something with wood as the medium. He studied product design, which was between architecture and design. Crafts are one of the most natural processes, according to Angawi. “The culture of craftsmanship has disappeared” since he wasn’t interested in being part of a factory and wanted to create unique pieces, reviving “th essence of making”, which is why he did a tour of multiple countries around the Middle East to learn in the old cities where he lived and studied. When he came back, he felt inspired by Makkah and by

the ideas of inhaling and exhaling, which is the act of absorbing cultures from all over the world and integrating them within the fabric of the city. So there is a collective and uniquely different cultural representation that truly enhances the spirit of Hijaz’s land: unity within diversity.

This spirit also exists in Islamic art. However, Angawi doesn’t stop there: he “documents, creates, then innovate”, which is considered part of the crafting tradition. So he learns from all the intangible heritage that exists then recreates it to ensure he understands the fundaments and then innovates to ensure its longevity for future generations.

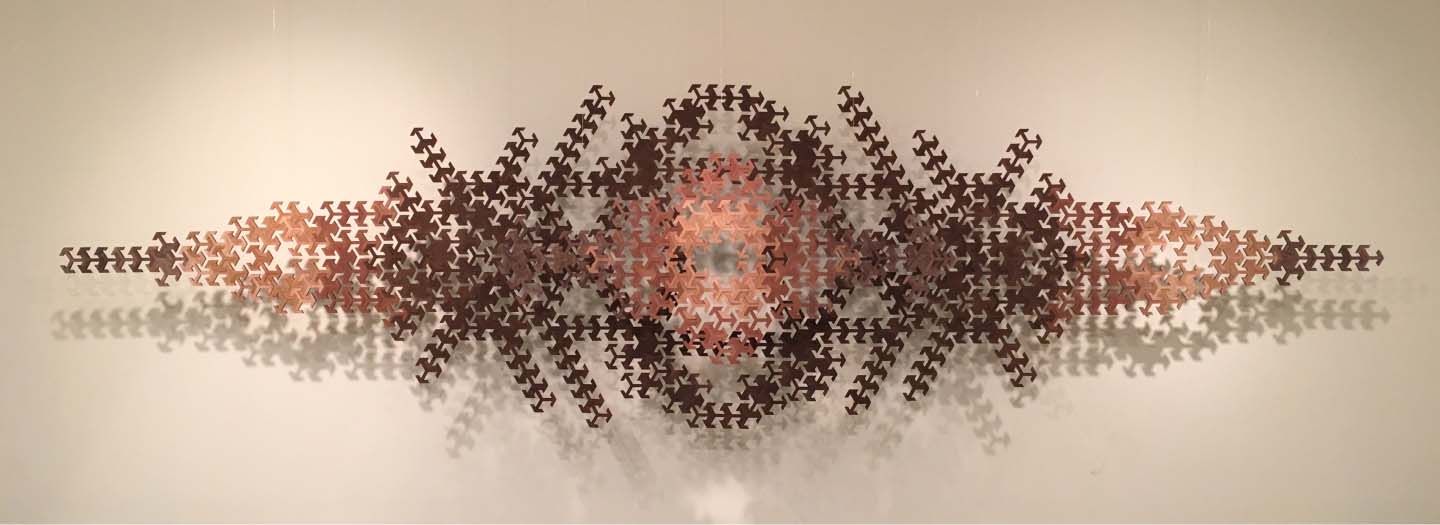

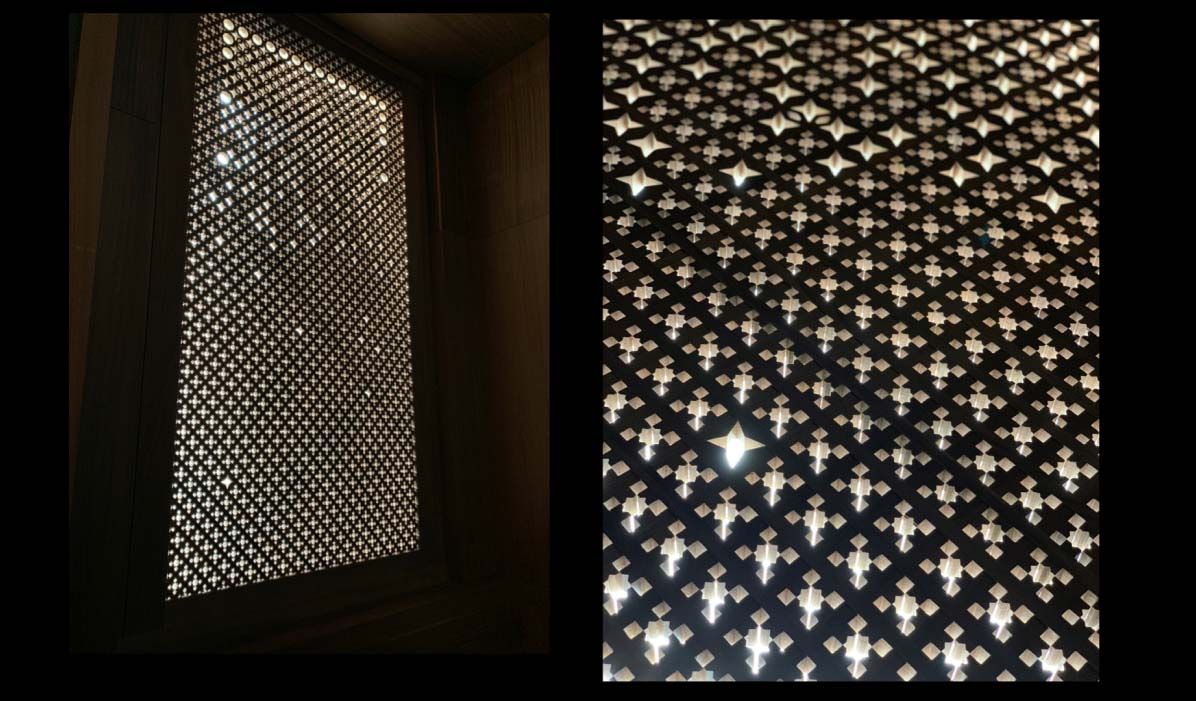

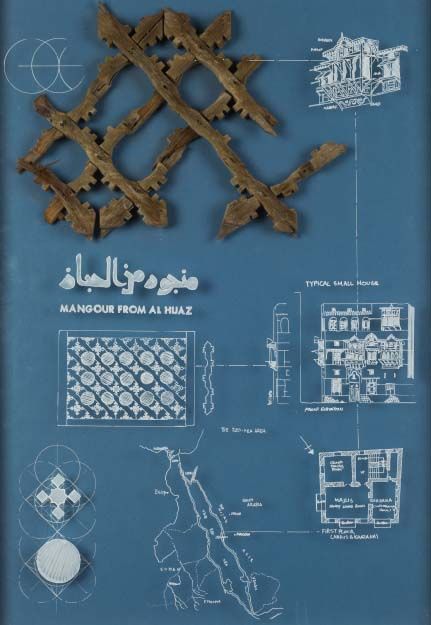

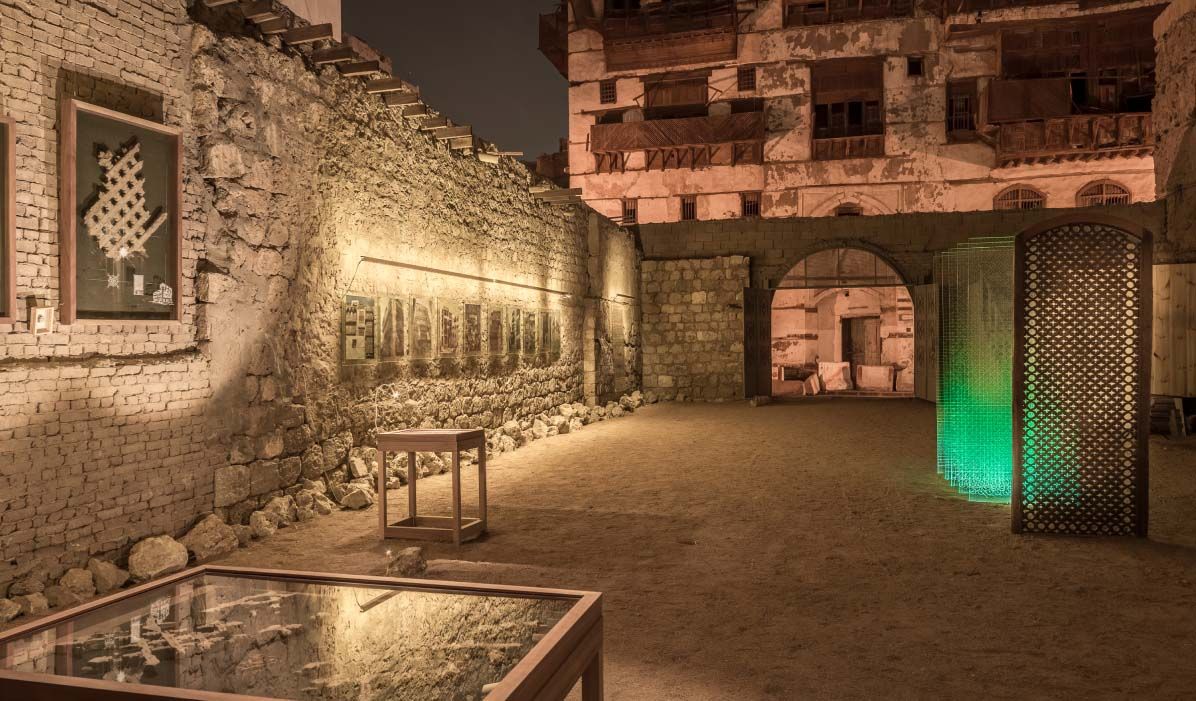

The crafty artworks by Ahmed Angawi.

In a sense, Ahmad Angawi isn’t influenced directly by any artist, but was impressed by the character of the maker with their multitudes. He is inspired by different disciplines. He found historically that people weren’t singular in their pursuits, they were scientists, artists, calligraphers, inventors, craftsmen. He found people like Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī or Leonardo Da Vinci interesting because they weren’t so singular. It is not surprising then that the label of artist can be somewhat limiting when compared to the actual effort he puts into his work. His work is a combination of multiple disciplines.

So how does he define himself? According to the artist, “it is an ongoing journey and I still want to discover and know. I know I am seeking something.” The act of exploring is a part of who he is to the point that creating a singular definition for himself is difficult. He uses multiple labels including artist, designer, craftsman, maker. “I am just a person who enjoys making things” says Angawi. The thing can be defined as the creation unfolds itself.

Hence, when asked: What Motto do you live by? It is “Jack of all trades is a master of none”, which reflects Angawi’s understanding of how humans want to learn about everything. When told that there is a continuation of the saying, he was surprised. “Jack of all trades is a master of none, but often better than a master of one”. It shows that being told that having one trade is more important than learning and branching out isn’t actually correct and being multidisciplinary has served Angawi in his work and his exploration.

Also, he is inspired by his legendary father. “My father always talks about scales: There is no balance without imbalance. There is no stable state, always something you seek, especially with heritage and tradition. It is mentioned in a lot of scripture so it has a deep meaning”. Since balance is a state we always seek, a tool we think with: “We need to balance a lot of aspects in our work including concepts like sustainability, the economy …etc. To balance all those things is to reach the ultimate state: equilibrium” and that is how Angawi approaches his work and life.

“Every person likes to choose their own weapon, aka tool”. The choice of wood is a natural one for Ahmed Angawi, literally in this case. Wood is a “live material” and there needs to be a relationship between the creator and the material to really build something beautiful. “When you can form it and shape it, it has a tolerance, it isn’t computerized, it is something natural”, he pulls into humanity’s love of wood, a part of our collective experience, including smell and feel. In turn, this connection with the

materiality of wood, especially qualitative ones, is what drives the design, informs how to shape the material, and inspires the work. It is also important to consider the local material and the need to have zero carbon footprint which is a historical practice; Nothing is wasted because of the scarcity of materials. Angawi reflects “this is also another way to ensure the sustainability of practices and that we keep our heritage and identity alive: using local materials and in the local way.”

Creations by Ahmed Angawi.

Sustainability is a key word for Angawi in his practice. Culturally and religiously, we believe that every material has its value and we shouldn’t waste it. “What does it mean to be islamic? Is it the patterns? Or is there principles and values that must be practiced. I believe that islamic art is the values and principles that you use in the work, which includes no harm no foul”. Most of Angawi’s work is informed by the three sides of sustainability: heritage, longevity, and environment. He understands that to do the Mangour, you have to understand its relationship with the Mashrabiyat, created from the ‘waste’ of the Mangour, and how that informs the airflow in a building.

These are all parts of the Hijazi architectural heritage but they all play a part in his relationship with his artworks. “We should celebrate technology but we are imbalanced” so we need sustainable practices to balance again. Part of that is to follow traditional practices, improve and innovate the creative process, recycle and reduce to produce more efficiently.

In the spirit of sustainability, Angawi also takes into consideration the environment of his work: “We are the inheritors of the earth and it was given to us to secure it and preserve it”.

He takes into consideration the materiality of the object from the conceptual stage and plans for how to reuse or recreate using the waste, the mistakes, and the random leftover pieces from his work. If it doesn’t end up fitting his plans, he stores them or reworks their use.

For example, he uses the leftover coffee grounds in his maker space Zawiyah. He collects ‘waste’ from around the Balad and Jeddah, including “homeless furniture” (pieces left on the curb) and gives it a second life by up-cycling, reusing and re-working the pieces. “The environment is always affecting my work.”

“Everyone has an inner designer/artist,” he said. Creativity exists in all of us: constantly learning and developing is needed to create beautiful artworks. “Beauty is the goal and it is the closest thing on earth to perfection.” It is important for any maker to understand what are they gaining from their practice and how their achieving that state of beauty. “We have to elevate three things through every process and experience: Body, Mind, and Soul. Your body is elevated from practice and the creation process. Mind is elevated when thinking, problem solving and creating new techniques.

Souls can be elevated through meditation and believing in your work.” This is a process of finding one’s authentic self to be able to create something true and beautiful in yourself without the noise of social media and with the simplicity of existing.

Sarah Abu Abdallah has always been interested in art as her mother Ghada Al-Hassan is an artist as well. She has been exposed to the art world from a young age, around 11 years old is when she feels is the official start, and has been a linear progression without much surprises all the way to getting her masters. So when did art start meaning something to her? “There was no Aha!

Moment. I always drew and always illustrated and planned to pursue painting but it felt too limiting then in college I got into video with layering and montaging as another way of narrating and telling stories. After university, I explored with Karam Natour arthouse cinema and video art where I explored more variety. Now I am back to painting in the same spirit as videos. It has become a cinematic painting, more dynamic, and everything goes and is meaningful”. Abu Abdallah’s narrative and creative outlet is linear in its progress yet her art shows a full exploration of context “Everything is a component of your experience and is meaningful to you. All the pieces of your life aren’t always translatable. Language doesn’t translate experience very well,”

especially when looking at experiences that transcend the norm and expresses the nuances of cultural and practical narratives. “We experience life in fragments and they make up the whole picture, your existence is an extension of that and the whole concept is existentialist.”

Art can bridge the gap between these fragments and show us a version of our existence from a certain lens and Abu Abdallah’s artwork shows us that. In that sense, her art is a product of understanding that “everything matters and doesn’t at the same time”—the significant is as important and meaningful as the insignificant.

Being significant isn’t the goal. So, while Abu Abdallah may be known as an artist, she prefers making art for one person. “If the artwork connects with one person then it has done its job”. For the artist, the connection the viewer makes with her art is more important than her connection with the viewer, no matter what their experience or understanding.

Sofia al Maria

Otobong Nkanga

Korakrit Arunanondchai

According to Abu Abdallah, the artists above have a sense of freedom in their art and don’t stick to one. They aren’t confined to one idea or medium and integrate their work seamlessly. “I like a lot of people and admire them but I actually think of these people’s arts and creative output,” she explains. There is no sense of urgency in their work and there is a level of authentic self expression that Abu Abdallah’s work does reflect and you can see it indirectly informs her production and content.

In the eastern region, there are specific tomatoes, which the artist discovered are called Heirloom Tomatoes, but were considered special ones in the region. People would save them, freeze them, gift them to each other.

They are considered luxurious. The tomatoes hav to come from the specific farms between the se and an oasis so there is an urban myth that ther are special minerals in the land that produced these tasty pieces. Hearing that the land was going to be developed, Abu Abdallah attempted to go and get some of the lands, but found the projects has already started and there was nothing left. She then attempted to get some seeds but the tomatoes sold out. “It was devastating to see the lands gone but no one cares about tomatoes” she commented.

Yet, she still had a show in Hamburg where she wanted to grow some tomatoes in a gallery space, so she tried to recreate the tomatoes. They weren’t perfect but they did the job. In Noor Arriyadh, by coincidence, she found the tomatoes again. The farmers had moved to a new land and are producing it again. She was able to actually closed the cycle by planting the actual tomatoes.

In my hometown, a lot of the farms are moving outside of the city center, which makes sense economically as they would be able to earn more money. The landscape where Abu Abdallah grew up is changing and that produces “sadness and sorrow”. This migration has been happening for decades. “People used to even burn down their farms so they can sell their lands and move.”

This brings to question for the artist the clean aesthetics of cities and malls and how they are taking over the lands, reducing the green spaces within the city limits and increasing the feeling of nostalgia and heartbreak. Juxtaposingly, bringing the farm and the tomatoes into a clean and polished gallery space is an act of distorting the environment. Abu Abdallah decontextualized the tomatoes and the gallery, inducing a feeling of harmony as well as a jarring feeling of irony.

This is especially true with the new trend of having plants indoors as presented in TikTok and other social media channels. “I would sit with my family and we would discuss what to plant in the family garden from jahanamiyah to yasmine. I think maybe because people live in sterile industrial spaces, plants are a way to balance things out.” She understands the importance of nature within our environment whether it is the sterile space or the more chaotic farm lands.

“I have a dystopian image of the future and don’t trust individual effort in creating real change. We produce just a fraction of the waste that industries produce so there isn’t much that can be done. Yet we still try to be more conscious about our consumption.” The act of reusing and giving life again to what many consider trash isn’t an act of sustainability but an act of reviving fragments of one’s life. Abu Abdallah has used an old car, magazines, and other items in her art to express new life, turning waste into precious art pieces or fragments of art pieces. In 2011, she wanted to get “junk and give it value in a playful manner. Art is precious and is associated with value, money, and sacredness.”

She used a car that another student had purchased for another project and painted in pink, giving it value as an art piece. When she was working on the Sharjah Biennale, she was asked to bring it back and the university threw it away.

She went in search of the car in junkyardsand when she found it, it was shipped to multiple art spaces all over the world. “It became this glorious art piece just through the act of adding paint when it really is nothing. There is a play on how the artist gives meaning to something and gives it value”. Art is as meaningful as the value it is given and Abu Abdallah has given many of her pieces new life and meaning through the simple act of interacting with it and adding some level of beauty.

Reflecting on her work, Abu Abdallah’s process has changed: “What I am making at the moment is not a series of conscious decisions, it is free expression. I sometimes take for granted the freedom associated with creation and acceptance of it as an art piece because I am an ‘artist’. Whatever we claim as art is art.” The space for exploration and development she has in a way reflects back to the artists who have inspired her.

“Everything starts with art.” It is important to develop the practice of art, your position, respond to open calls, ensure your integrity, and build the correct network. Before all that, focusing on developing the art and educating oneself is the most important part of developing yourself as an artist and improving your artwork. “Just make and the rest will follow”.