The Art of Plants

Botanical art is one of the most meticulous and dedicated forms of art that brings nature’s treasures alive. For decades, Sue Wickison has been perfecting this art, capturing a world few get to see in real life.

With an impressive list of accomplishments and awards, Sue, who was born and brought up in Sierra Leone, West Africa, was influenced by her father. A teacher, amateur botanist, and an artist, Sue’s father saw the same love of nature and passion in his daughter and so would take her on adventures and expeditions locating, identifying, and collecting botanical specimens.

Often, plants and the heritage around them are taken for granted, but thanks to dedication by artists like Sue, and the recent push to protect the natural world, plants are getting the attention they truly deserve.

“Helping to record intangible plant heritage is critical for maintaining the cultural diversity of societies and promoting sustainable relationships with the environment. Efforts to safeguard this heritage may include documenting traditional knowledge supporting community-based conservation initiatives,” said Sue, who plays an important role in visually documenting this natural world.

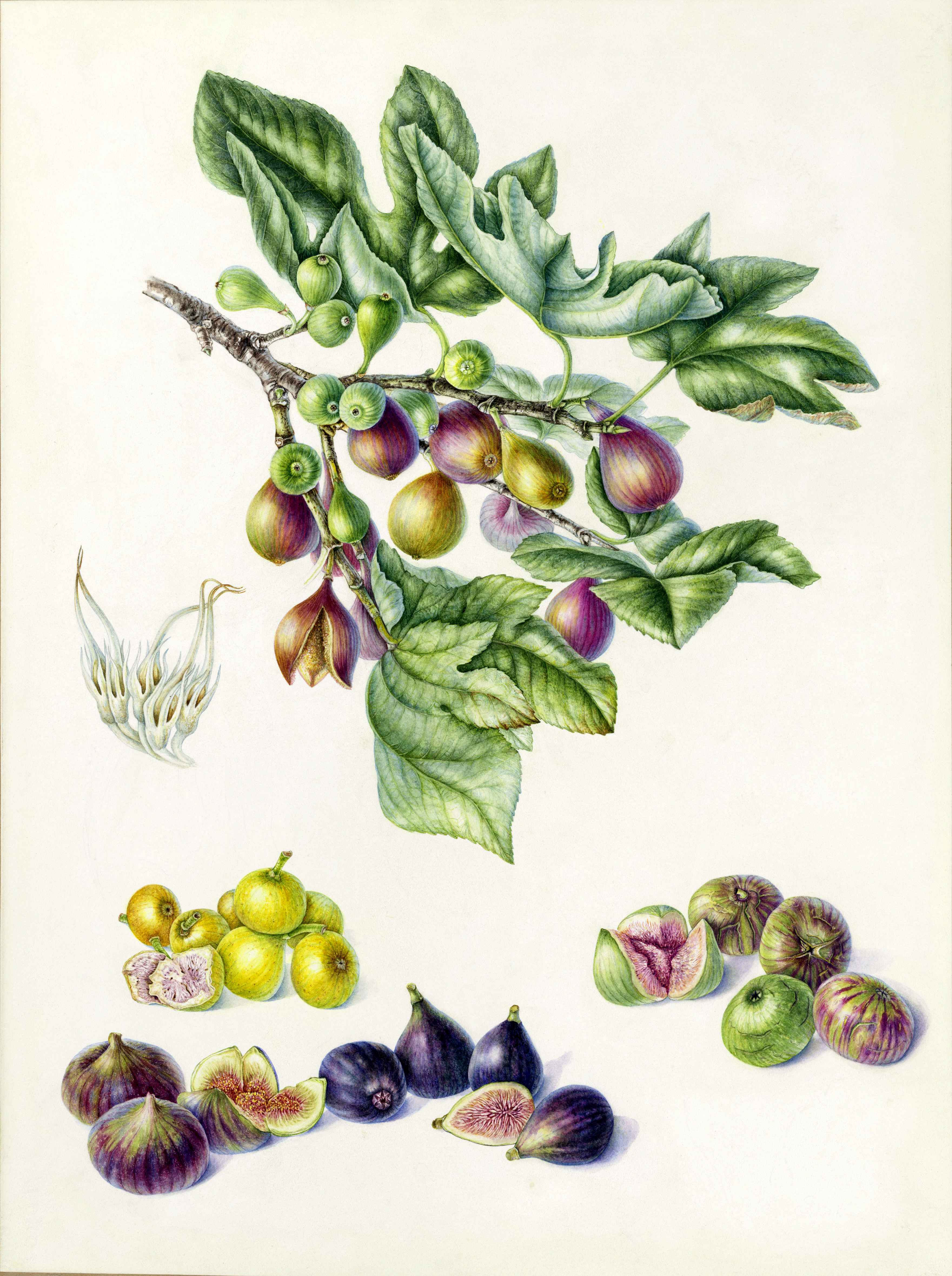

She likes to highlight rare and endangered species to bring awareness to them and garner support for their protection. Her latest project, ‘Plants of the Quran, History and Culture,’ is the culmination of many years of research and dedicated hard work between two women. From a tiny mustard seed to a majestic date palm, and obscure plants of the desert to well-known culinary staples such as figs, onions, lentils, gourds and olives – this book is a truly unique body of work.

Ithraeyat met up with Sue, and is privileged to showcase her latest work as part of this special edition dedicated to intangible heritage.

Art is an enriching passion in my life. It’s a journey of continual learning, inspiration, sharing, and communication, which I hope gives pleasure to others as well. It is a form of heritage and a handmade skill in a world increasingly reliant on the digital. There is a responsibility and fascination to record plants accurately in a number of different formats, whether for books, postage stamps, on fabric, packaging or historical records for posterity.

Sue Wickison, botanical artist, amongst her wonderful pieces from The Plants of the Quran.

Being born and brought up in Sierra Leone, plants were always a part of my life, and I was taught from an early age by my father, an amateur botanist, to closely observe, respect and tell the difference between plants when out collecting with him.

That was the initial catalyst that later led to a degree in scientific illustration, specializing in botanical illustration, and then working at the Royal Botanic Gardens Kew in the UK to record different plant families for various publications.

A full career circle later, I have just completed a well-received five-month solo exhibition at Kew in London to showcase the Plants of the Quran. This has been an eight-year project that also culminated in a collaboration with Dr Shahina Ghazanfar, a senior botanist at Kew who researched and wrote The Plants of the Qur’an, History and Culture, published and available from Kew Gardens, London.

Painting of figs. Art courtesy of the the artist.

There are several stages to complete a piece of work. Working from living material is essential for the accuracy and authenticity of the work. Research, travel to different countries, field notes, preliminary sketches, and color notes to fully understand the plant species and its characteristics are the precursors to composition design and the final illustration. The whole process takes many months to complete as the illustration process is meticulous and very studied, using tiny sable brushes to build up layer upon layer of delicate details. Dividers are used to measure the plants accurately, and microscope dissections of the flowers add another layer of education and understanding of the plant.

The initial inspiration came during a visit to the Grand Mosque in Abu Dhabi in 2015. The whole mosque was breathtaking. When I looked at the extensive botanical motifs on the floor on the columns and walls, I wanted to find out what they represented. There was very little information, so I wrote to a colleague at Kew Gardens, and he put me in touch with Shahina. It was a serendipitous introduction – she had been researching and writing a book about the plants of the Quran for years.

So, from an idea as small as a mustard seed grew a collaboration with Shahina to write and me to paint all the plants mentioned in the Quran. This grew over eight years to culminate with the publication of the book and a successful solo show at Kew Gardens in London with millions of views on social media. All very humbling

Ethiopian banana tree. Art courtesy of the the artist.

The date palm illustrated over two paintings, both well over 1.2 meters in height, shows the flowering stage with the dissection of the male and female flowers and the mass of hundreds of dates in the fruiting stage, both painted over a two-year period with flights from New Zealand to Sharjah in the UAE to collect and carefully record each stage. The actual painting took months to complete.

Heritage in faith really resonated with me after speaking to a friend, Jameela, about the date palm seed. She related to the seed from the strength of her Muslim faith and told me about the Fateel, the thread or funicle that joins the seed to the inner side of the fruit, and the qitmeer (or protective sheath) around the seed. I was aware of both, which she used as a unit of measurement from the Quran to judge your deeds, good or bad, however small it may seem.

Then she mentioned an even smaller aspect of the seed, the naqeer (or dimple in the seed), which I was not aware of.

So, in the necessity of science, I had to eat a few more delicious dates, and sure enough, this tiny dimple was there, but how had I missed something so important? A measure of good deeds or the actual point of emerging germination?!

This is a heritage of belief and using plants as reminders of everyday lessons.

“But those who do good—whether male or female—and have faith will enter Paradise and will never be wronged even as much as˺ the speck on a date stone.” – Dr. Mustafa Khattab, the Clear Quran

I learned from that moment to look even more carefully and that, regardless of our creed or culture, close observation is the common thread between all of us and is our strength to share and impart information for the betterment of all.

Stay inspired, show compassion, be kind, and try to help others where you can.

- Ferdinand Bauer (1760-1826), who spent a lot of time in the field with living material and developed a unique shorthand system of covering drawings with a map of tiny numbers. Each number represented a color, relating to his own chart of up to 1,000 different colors and hues. With this formula the work could be completed, sometime years later with incredible accuracy.

- Sydney Parkinson was employed by Joseph Banks to travel with him on James Cook's first voyage to the Pacific in 1768, on the HMS Endeavour. He was the first illustrator to record plants from Australia and New Zealand and worked in incredibly cramped conditions to record plants for posterity.

- Marianne North (1830 – 1890) was a prolific English Victorian biologist and botanical artist, notable for her plant and landscape paintings, and her extensive foreign travels alone.More than 800 of her paintings are still housed today in a gallery at Kew.

Canvas of pomegranate plant and fruit. Art courtesy of the the artist.

It is a fascinating form of the arts, requiring careful observation skills and a lot of slow, meticulous patience. It also requires a certain knowledge of botany and the need to work closely with scientists to record the accurate characteristics of plant species in a precise and aesthetically pleasing way. There are numerous books and courses on the topic and this website of Katherine Tyrrell’s https://makingamark.blogspot.com has a huge amount of information.

Plants remain essential to life.

Pomegranates are a symbol of fertility and immortality in many cultures and the pomegranate is one of the fruits in heaven. It is also a good food source that will store well thanks to its leathery protective skin.

Their challenge for me was to capture the subtle color changes through the delicate petals and the contrasting outer hard, shiny calyx. The fruit is made up of a mass of juicy cell-like arils, each one a different shape from the adjacent one. Capturing the shine and transparency to show the seed hiding inside was an interesting challenge.

The twigs of Salvadora persica (or toothbrush tree) are still used today as toothbrushes. The benefit is that the skin on the twigs possess an antibacterial property to assist with gum hygiene.

Lawsonia inermis (or Henna) is used extensively for ceremonial purposes that have not changed across the centuries. Crushing the leaves of the plant to create the dark rich red coloured dye for intricate patterns on the hands and arms is common to a number of cultures for special events.

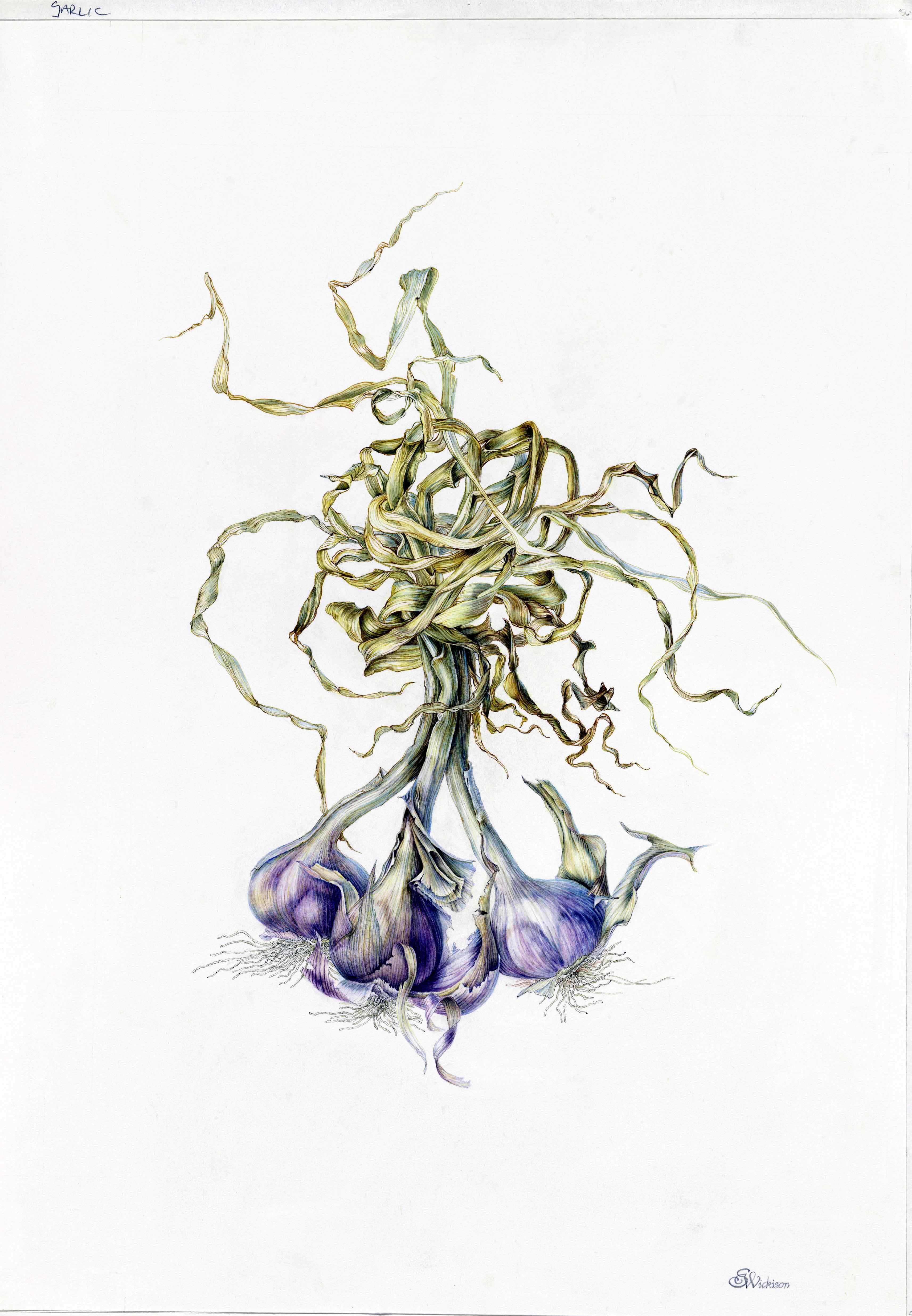

Traveling to find Allium sativum (or garlic), I went up into the Al Hajar mountains of Oman to see how garlic had been grown for generations. I was given access to a beautiful, purple-hued garlic from the growers in the area. This useful plant has widespread medicinal and culinary uses including antimicrobial, and anticancer qualities.

Purple-hued garlic. Art courtesy of the the artist.