How Identity Shapes Art

Portrait of Dia al-Azzawi by Chris Wood.

“I often presented my work as an Arab artist with its geographical and cultural extension, and that my artistic research was related to my knowledge of Arab culture in all its comprehensiveness, and that this research had a method that had an Arab dimension in the artistic imagination or in its cultural interpretations.”

Dia al-Azzawi

Azzawi was born in Iraq in 1939 and studied archaeology at the University of Baghdad, and arts at the Baghdad Academy of Fine Arts after the guidance of his teacher Hafez Al Droubi. He graduated in 1964. Azzawi, who was studying archaeology and the ancient world during the day, and at night studying European painting, says: "This contradiction means that I have been working with European principles but at the same time using my heritage as part of my work."

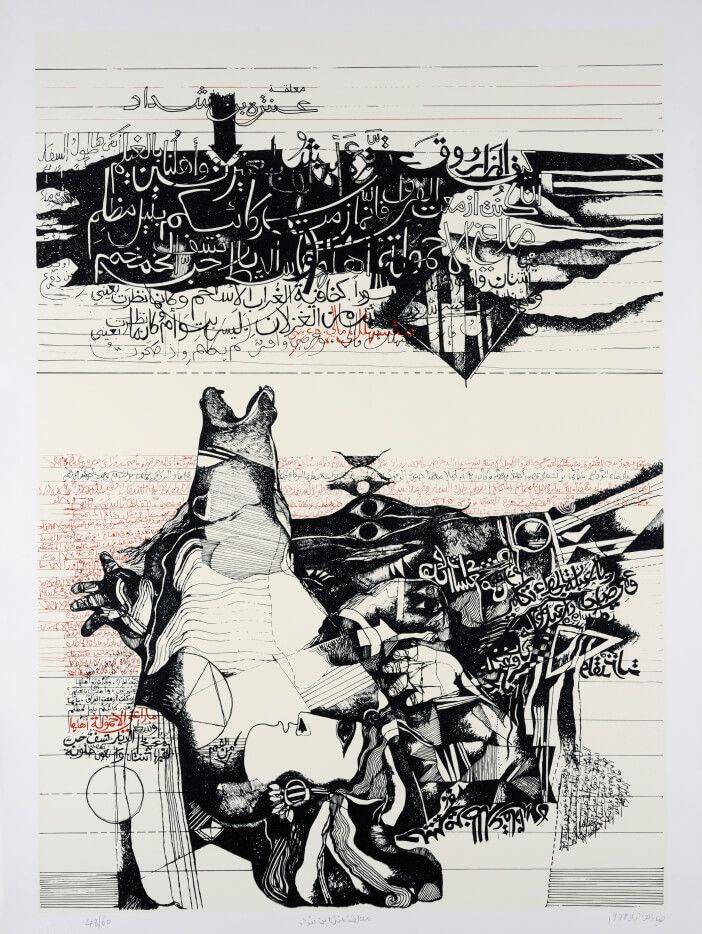

During his studies at the Academy, he became involved in artistic groups and intellectual schools, such as the local art group, known as the Impressionists, which was under the supervision of his mentor Hafez Al-Droubi, and the Baghdad Modern Art Group under the supervision of Shakir Hassan Saeed. Azzawi then created his own art group known as the “New Vision”. Through his studies of archaeology and his familiarity with the history of Iraq and the civilizations that came to it, Azzawi developed his own artistic style, where the theme of Arab cultural history and myths – such as the ancient Epic of Gilgamesh, and the martyrdom of Imam Hussein – were present in his works.

After his graduation and prior to his permanent move to London, Azzawi held the various positions at the Iraqi Department of Antiquities in Baghdad (1968-1976), and later became artistic Director of the Iraqi Cultural Centre in London, where he arranged a number of exhibitions, and was also editor of several magazines such as Ur Magazine (1978-1984) – which is a magazine issued by the Iraqi Cultural Centre in London – and Arab Arts (1981-1982), and a member of the editorial board of the scientific magazine "Mawaqif".

Azzawi experienced turbulent and critical political periods in the region, especially in his country Iraq and the occupation of Palestine. These events had a tremendous impact on his artistic production, which became grounded in the acts of reflecting political events.

Azzawi was from the generation of people who witnessed the fall of their countries and homelands under bloody dictatorships and fierce wars that led to continuous destruction. He decided to be a human first before being an artist. His work was a realistic mirror that reflected the destruction, blood, and blackness that afflicted the region and it was a resounding voice for the voiceless.

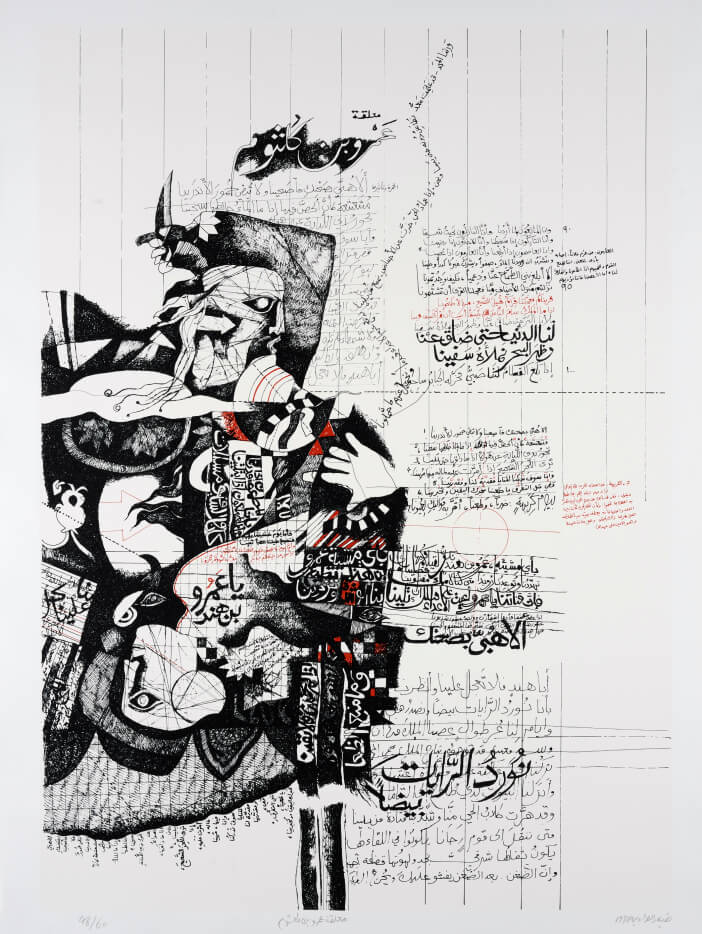

Azzawi's work incorporates various elements of Arab cultural symbols, with calligraphy, literature, and poetry as its essential component. It was distinguished by its historical narrative of the wars, massacres and destruction that the region was going through, and mixed Arab heritage with modernity, a recurring theme in his work.

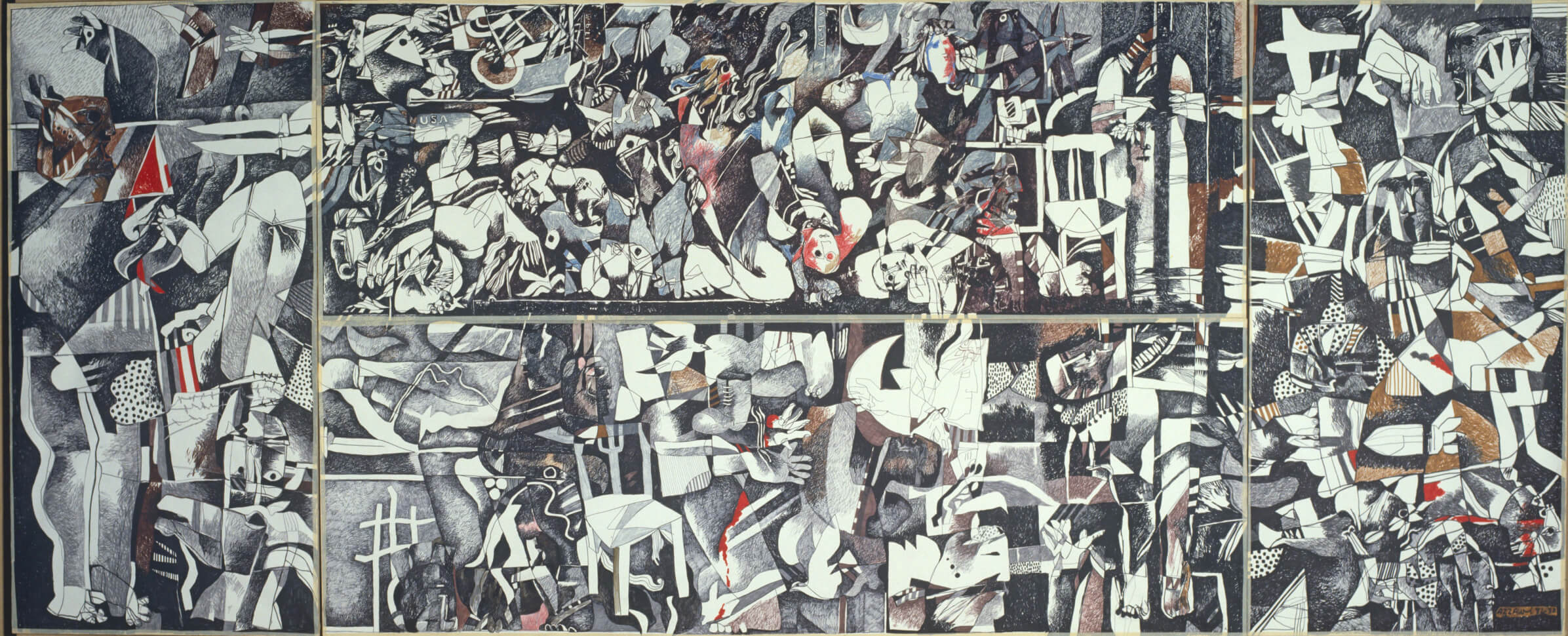

’Sabra and Shatila Massacre,’ by Dia al-Azzawi. 1982-1983.

Ink and wax crayon on paper mounted on canvas, 3000 x 7500 cm.

Part of Tate Modern Collection in London.

Had it not been for Azzawi’s Iraqi identity, he would not have been the artist we know today. His upbringing in Iraq played a major role in forming his identity. He grew up in a crucial period for Iraq and the entire Arab World, where wars, massacres, displacement and occupation were the norm in the region. Furthermore, the region was in a state of tension and chaos after the English colonization and the dominance of the Arab nationalistic discourse in the region, which aimed at highlighting the Arab identity, pride in the homeland, sincere loyalty to Arab unity, attention to political and social issues and promoting a general atmosphere of fraternity, synergy and solidarity among the people.

Azzawi studied in the sixties in Iraq and was influenced by the art groups that emerged in that period. He witnessed the emergence of a group of brilliant artists such as Hafez Al-Droubi, Jawad Selim and Shaker Hassan Saeed, who had the greatest impact in shaping the fine art movement in Iraq. The movement celebrated heritage and history, created art schools and styles unique to European art, and called for renewal, modernisation, innovation, and avoidance of limitations and narrow-mindedness in artistic production.

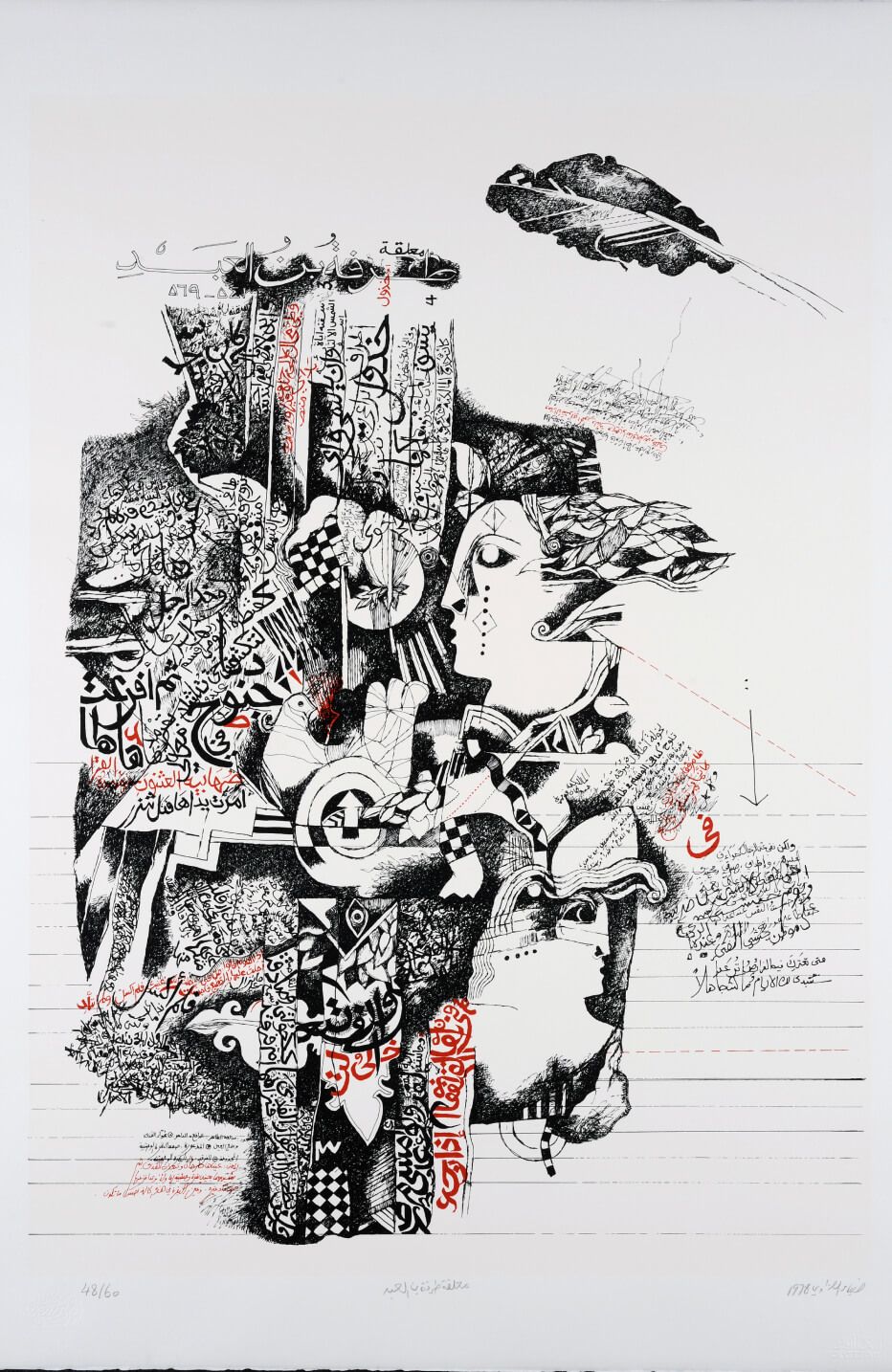

'The Thousand and One Nights,’ (Special Edition). By Dia al-Azzawi. 1986. engravings, etchings and lithographs, 66 x 50 cm, ed. 25/25. From the collection of Dalloul Art Foundation.

'The Thousand and One Nights,’ (Special Edition). By Dia al-Azzawi. 1986. engravings, etchings and lithographs, 66 x 50 cm, ed. 25/25. From the collection of Dalloul Art Foundation.

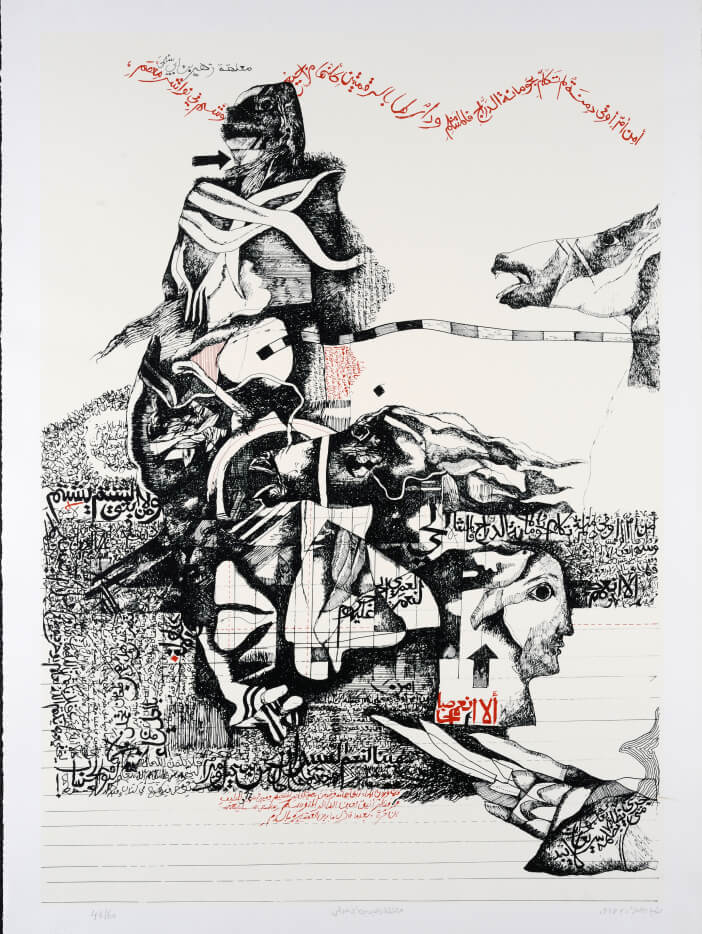

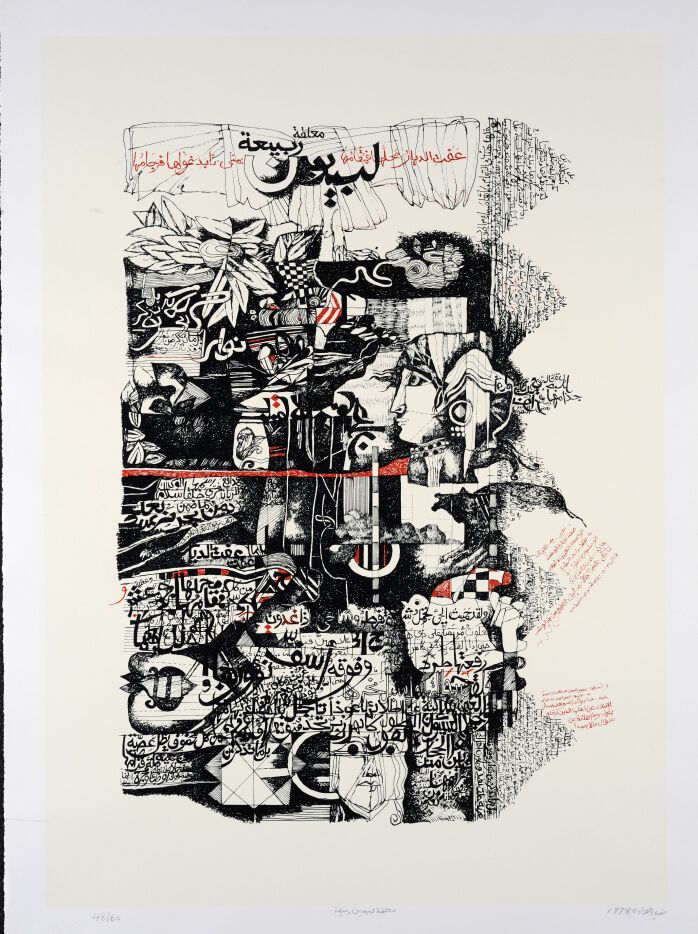

Perhaps the most prominent characteristic of Azzawi’s work is the contradictory duality in which he oscillates. Sometimes most of his work depicts destruction, blood, wars and massacres, as in the case of his most famous paintings, “Sabra and Shatila”, and his painting collection “We are only seen as corpses” that depicted the horrific state that the human soul may reach from killing and shedding the blood of the other just because he is the other. Other times we see Azzawi celebrating his Arab culture; the presence of the letter in abstraction, poetry and literature is evident in his work in “the Seven Odes” collection which celebrates poetry and “One Thousand and One Nights” collection which celebrates the ancient art of fiction.

Azzawi was an artist who gave his Arab culture and identity its due and did not underestimate it. He was sincere in portraying the painful political events and ugliness from war which are still part of Arab reality, without turning a blind eye to the beauty by which the Arabic language, literature and poetry are unique.

Q1: Can you tell us about your background? How did you start as an artist? How did you enter the artistic community in Baghdad? What artistic and cultural forms have most influenced your style and work?

My academic studies of archaeology and civilization, and at the same time my art studies at the Institute of Arts, formed my cultural and artistic background. This contrast between the historical dimension of various civilizations and the history of contemporary European art was my motivation for finding a method that combines them. At the same time, the Mesopotamian legend and its rich content was my greatest artistic challenge, represented in making it an acceptable achievement that contributes to the interpretation of contemporary phenomena.

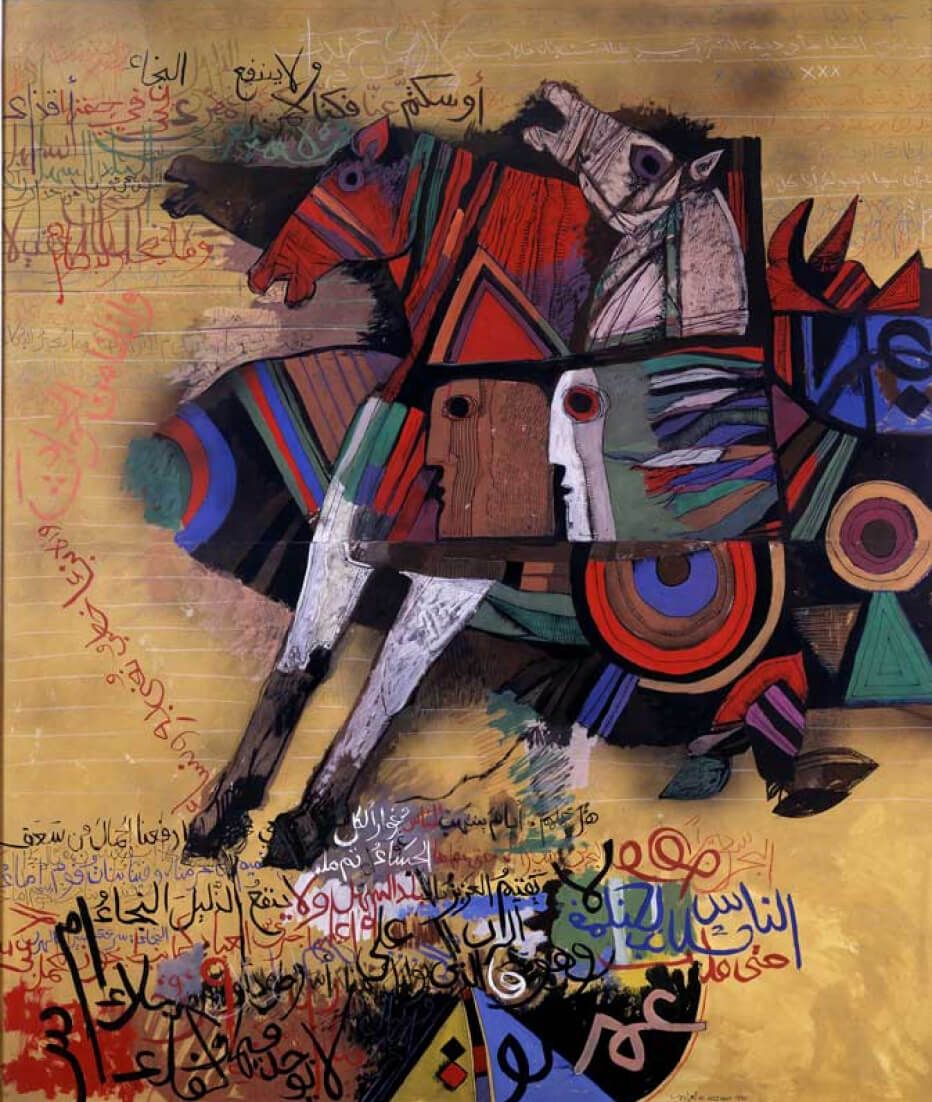

‘The Ode of al-Harith bin Hilza,’ by Dia al-Azzawi. 1980. Gouache on paper. 140 × 118 cm Courtesy Kinda Foundation. Part of ‘Amakin’ exhibition by SAC.

Upon completing my art studies in 1964, I participated for the first time in the group exhibition of the Iraqi Artists Association, and I did the same in the following year. Then I had the opportunity to affiliate with the Iraqi Impressionists Association, which was founded by the artist Hafez Al-Droubi.

At that time, my work was received with a press welcome because of its artistic and civilizational dimension that is close to the experience of the Baghdad Modern Art Group, which was founded by Jawad Selim, who called for the realization of Iraqi art linked to the national identity.

Q2: As your artwork is increasingly being shown to a Western audience, what role do you want your work to play as part of the discourse on Arab art?

I am like any creator who seeks to achieve artistic excellence with a dimension related to his cultural and popular heritage, and with this distinction the artist is an effective contributor to expanding the circle of visual and cognitive dialogue with other cultures, which thus reduces the deliberate distortion by some newspapers and social media of our Arab societies.

Q3: What are the most common topics in your work? And why?

In the beginning, my topics were related to myth and folklore and what they needed to develop signs and forms taken from the legacy and in a way that distances them from their past. The Epic of Gilgamesh, for example, was addressed and viewed from the angle of human fear of death and the impossibility of immortality. From here, myth or folk narratives can be a means to achieve a rich artistic world interpreted according to the viewer's perspective and culture. After that, I relied on topics related to daily life, and the scenes and discoveries of knowledge in the contemporary life that various travels afford me.

Q4: How do current political, social and global events affect your work, and how is the medium that you use or try in your work chosen?

A person cannot isolate himself from the life that surrounds him, and no intellectual from a moral standpoint can abandon his contribution to the development of society and the expansion of his human perceptions. Man is a social being, and therefore he must deal with political issues, as they have a direct impact on the public life he lives and on the future of his family. For me, the Palestinian right, and the devastating societal pressures that Arab societies are subjected to, constituted the most important thing I tried to express. These pressures took away the young generation’s dream of change that is inseparable from human development and necessary for normal life.

It was not easy not to protest in an artistic way about the massacres of Palestinians in Tel Al Zaatar, Sabra and Shatila, or the destruction of simple peasant farms. And it was not easy not to protest and insist on exposing the systematic Western barbarism in the dismantling of Arab societies through military and political methods, which elicits puritanical concepts to explain Arab history to reach the natural resources possessed by these societies.

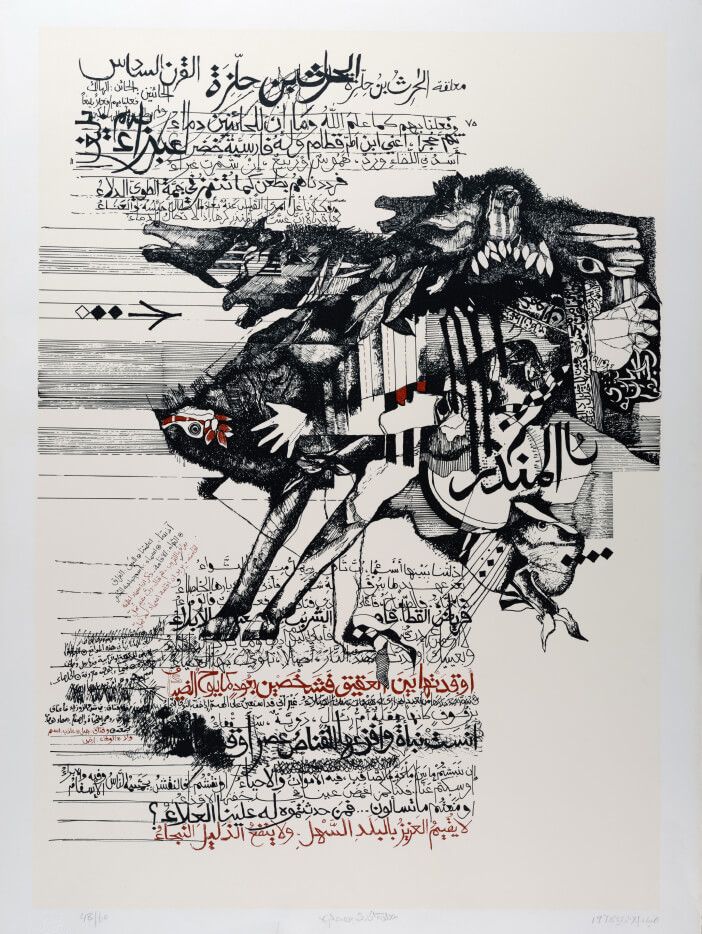

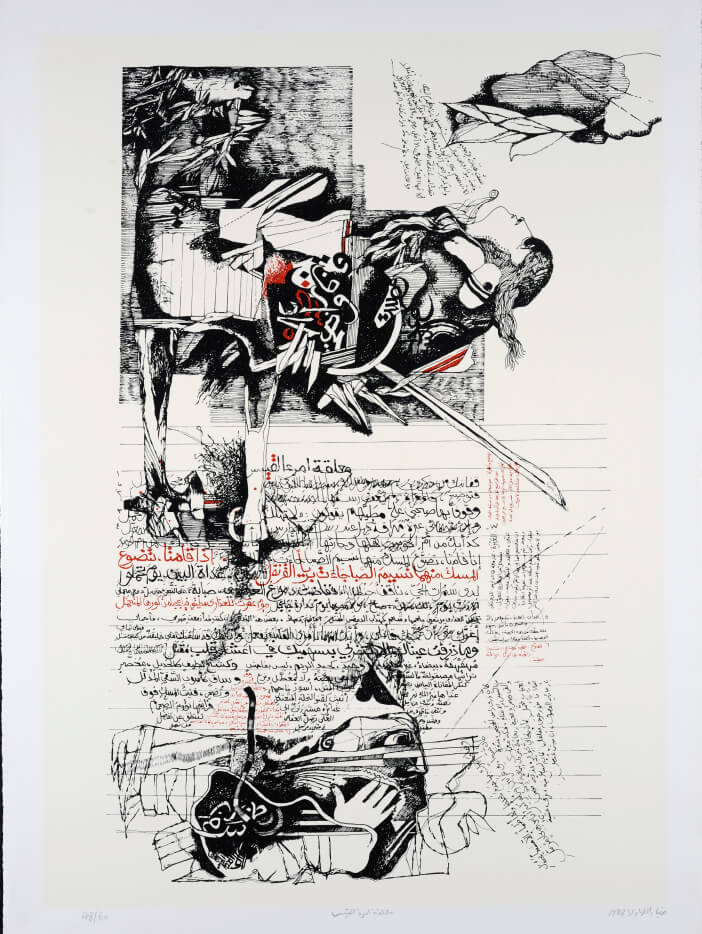

The Seven Odes (AL-MUA’ALAQAT) by Dia al-Azzawi. Tarafa bin Al-Abd ode. Lithographs (4 of 8), 105 x 73 cm, 1978. From the collection of Barjeel Art Foundation.

Q5: How does your identity as an Iraqi living outside his country affect your work?

I left Iraq when I was in my mid-thirties, and I had an artistic experience that helped me open up to the culture of the new society, and my studies of archaeology were an important factor in preserving what I had of historical knowledge. Over the years, the diverse cultural heritage in Iraq between Sumer and Assyria and Islamic civilization no longer belonged to us as Iraqis, but rather it belonged to all of humanity, and therefore one of its features is that it rejects national fanaticism. I often presented my work as an Arab artist with its geographical and cultural extension, and my artistic research was related to my knowledge of Arab culture in all its comprehensiveness, and that this research had an Arab dimension in the artistic imagination or in its cultural interpretations.

Q6: What are the most important events that shaped and contributed to establishing your artistic path, or some of which led to a political character?

Perhaps the Palestinian issue is the decisive factor for the political orientation in artwork. I am from a generation that was raised on the Palestinian issue, and the failure to deal with it was part of the principled position to defend the right that was robbed by Western settlement societies.

Subsequently, this topic was adjacent to what happened in Iraq; the Western targeting of wrong Iraqi policies that ended with its occupation, under a fabricated pretext and the emergence of a corrupt political class that divided the members of society.

The Seven Golden Odes: Zuhayr bin Abi Salma, 1978. 103 x 72 cm, ed.

The Seven Golden Odes: al-Harith bin Hiliza, 1978. 103 x 72 cm, ed.

The Seven Golden Odes: Labid bin Rabi'a, 1978. 103 x 72 cm, ed.

The Seven Golden Odes: 'Amr bin Kulthoum, 1978. 103 x 72 cm, ed.

The Seven Golden Odes: 'Antara bin Shaddad, 1978. 103 x 72 cm, ed.

The Seven Golden Odes: Imru al-Qays bin al-Hujr, 1978. 103 x 72 cm, ed.

Q7: What do you hope to achieve through your work? And who is your target audience? In general, how does the audience respond to your work?

What I produce represents my position in life; I do not target a specific society and I do not want to be an image of the Arab who only knows his culture. Over the years, my work has become present in Arab and foreign groups, which is a recognition of the professionalism of my experience and its ability to be part of the culture of other societies.

Q8: How do the Arabic language, poetry, culture and literature influence and shape your work? Why?

Poetry and literature have the lion’s share, as it is said in my general culture, and since the sixties I had a variety of interests in reading Iraqi and Arabic novel and poetry. Because of my studies of archaeology, I had the opportunity to learn about the poetry of the Sumerian and Babylonian myth, and over the years my interest extended to contemporary Arab poetry, and I became friends with many poets. This knowledge motivated me to go beyond the painting, to produce poetry books of varying size and material, as well as diverse in the way they are produced as unique original works or printed and limited copy works.