A Taste of History

"Preparing Medicine from Honey", from a Dispersed Manuscript of an Arabic Translation of De Materia Medica of Dioscorides, Calligrapher 'Abdullah ibn al-Fadl dated A.H. 621 / 1224 CE, from The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Although written over a thousand years ago, I have to agree with him: food is one of the great pleasures of life. Food is essential to all human cultures, but recipe writing first appeared in Mesopotamia around 1700 BCE. A collection of cuneiform tablets features 35 recipes, ranging from simple stews to complex bird pies. Composed in Akkadian in the middle of the Old Babylonian period, it’s the world’s oldest cookbook.

“There's one recipe from this collection that to my mind is obviously a tharid,” says Daniel Newman, Chair of Arabic Studies at the University of Durham (UK) and author of The Sultan’s Feast. “They talk about cake, they talk about crumbling the cake, and pouring a liquid broth on vegetables and meat. That's tharid!” Incredibly, this is one of those foods that people have been making and eating for thousands of years. It can be the food of the poor as well as the wealthy, especially when prepared with luxurious ingredients such as eggs and bone marrow.

As early as the tenth century, al-Muqaddasī, the famed Arab traveller from Jerusalem, wrote that he had “eaten harīsa with the Sufis and tharīda with the monks and casīda with seamen.” All these dishes were famous medieval Arab preparations that have their descendants today.

It was in the Sassanid courts that gentlemen first began keeping recipes, but it was the Abbasid Caliphs who commissioned the invention and recording of new dishes, as well as poems and songs about food. Other Baghdadis were eager to feast as the caliphs did, and the passion for cooking soon moved beyond palace walls. There was a sudden explosion of Arabic cookbooks from the 10th to 13th centuries, many of which have disappeared. Ibn Sayyar al-Warraq’s 10th-century Kitab al-Tabikh (Book of Dishes), is the earliest known title.

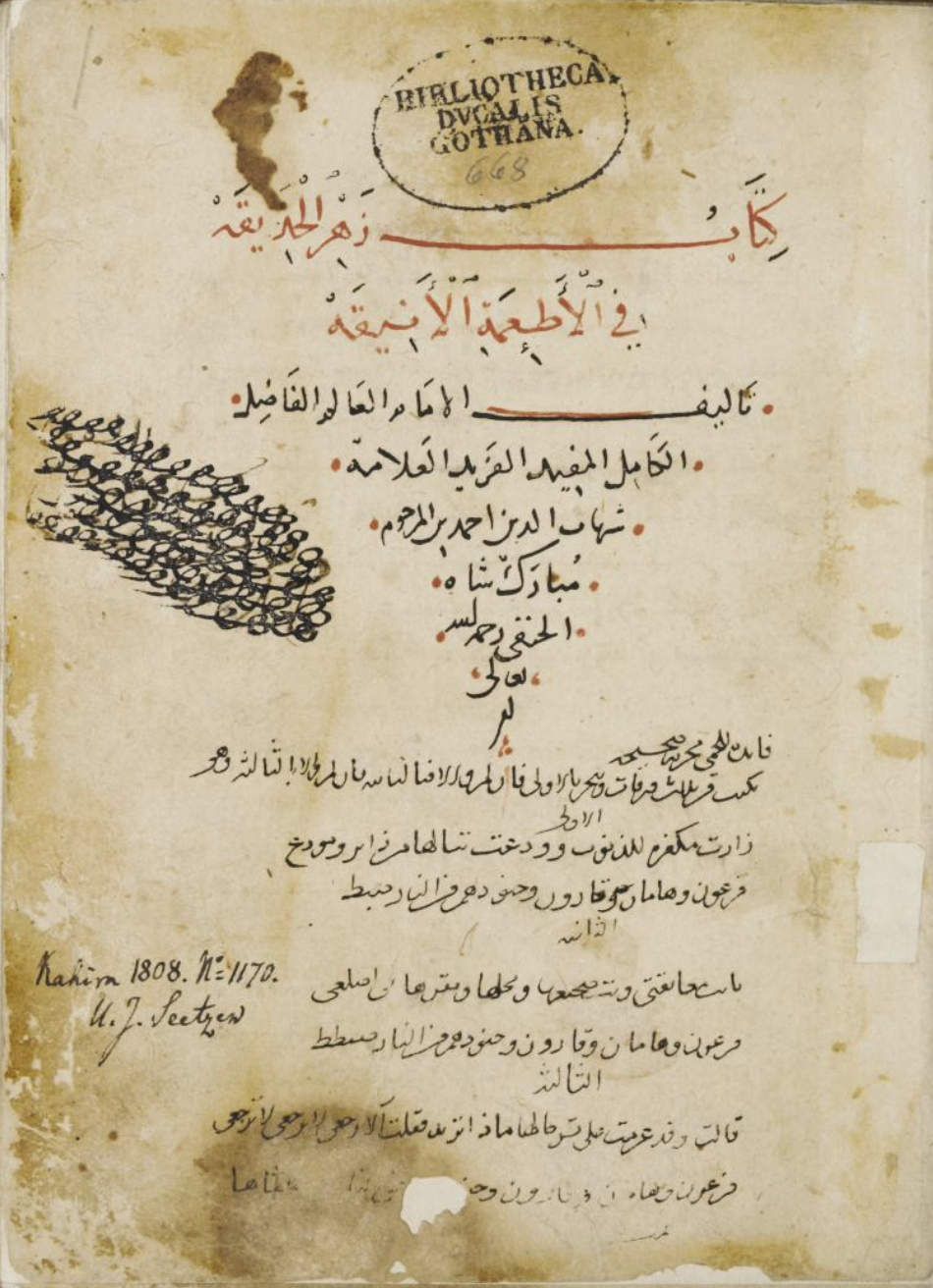

Ibn-Mubarak-Shah-cover. courtesy of Daniel Newman.

Kitab al-Tabikh contains more than 600 recipes from the Abbasid era, ranging from soups and stews to meat dishes, sweets, and condiments. It also includes information on cooking techniques, ingredients, and utensils, as well as advice on table manners and etiquette.

One of the most prolific recipe-creators was the famous poet, singer and gourmet chef Ibrahim ibn Al Mahdi, the half-brother of Harun Al Rashid, who along with Bida’a, his favourite cook and concubine, spent countless hours creating opulent dishes in the court kitchens.

“Remember that you're dealing with an elite cuisine. In some cookbooks, we have references to a dish liked by shepherds - but these are not very common. Al-Warraq is a combination of a cookery book and a work of literature – part of that mysterious and elusive Arab genre: adab. He provides information about elite Abbasid society but doesn’t tell you much about common society and their food habits.

However, as we know, what the elites eat trickles down to what the nobles eat who want to emulate the court. And then what the nobles eat, trickles down to what the general population eats.”

But dinner parties were not made by food alone. Hosts and attendees were expected to smell sweet, with fresh breath and clean hands. If you wanted to eat like medieval Arab royalty, then you first had to smell like medieval Arab royalty. We find instructions on the etiquette of washing and perfumery as part of the cookbooks. Diners at that time largely ate with their hands, so it was important to wash, preferably with a sweet-smelling soap, before and after the meal.

In Scents and Flavors, a 13th-century Syrian cookbook, a saffron-and-carnation-based washing powder was used by Caliph al-Ma’mun, while clove-and-cardamom was the favourite scent of Harun al-Rashid.

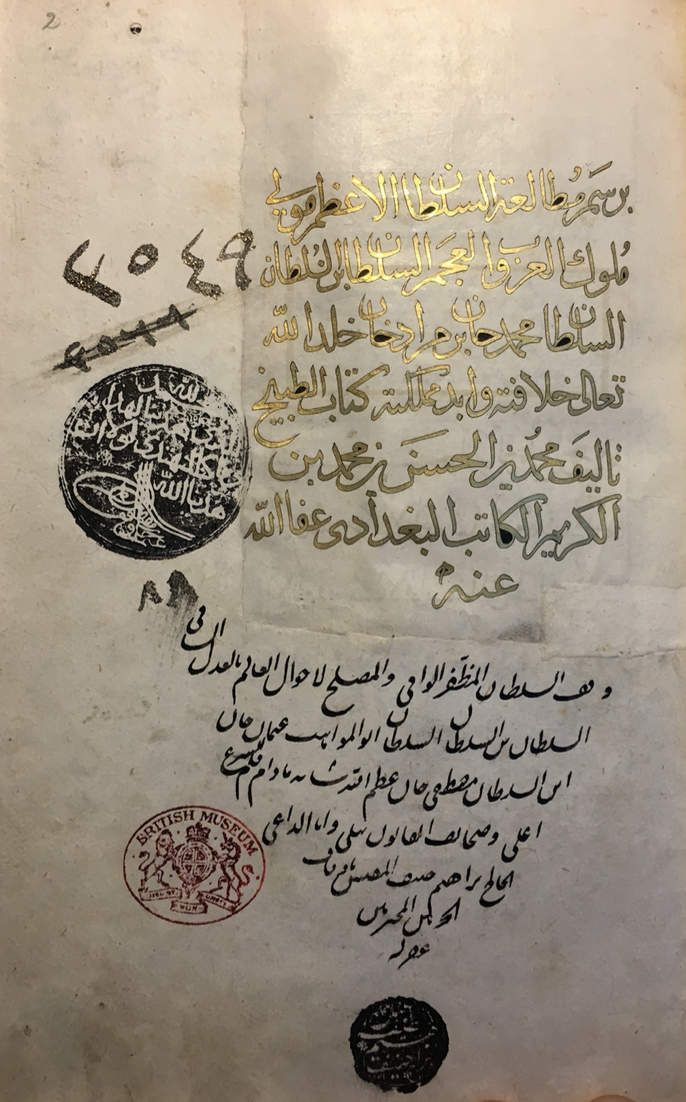

Al-Baghdadi cover. photo by Daniel Newman.

The 14th-century Egyptian cookbook, Treasure Trove of Benefits and Variety at the Table, tells us that a “cook should be an agreeable person.” The author goes on to make suggestions about the types of cooking pots that work best (soapstone), what sort of firewood should be selected, and how a chef should clean their utensils and select their spices.

Newman adds, “We must consider several strands within the medieval Arab cooking tradition. One is the Sassanid Persian origin of many dishes. Another is the connection with medical literature. We already know from people like El Razi and Ibn Sina, that food is medicine, and medicine is food.

I've looked at a 15th-century Florentine collection of pharmaceutical books, and lo and behold, there are many recipes that are carbon copies of the Arab ones. The third element is nutrition, courtesy of people like El Mas’udi, who gives us very detailed information about the rulers’ private physicians and the role they played in their food and diet. Food was considered medicine, and so the lines between nutrition, pharmacology and dietetics were very blurred.”

According to Arab Muslim tradition, food was part of a holistic view of humanity and medicine needed to taste good. “In the Middle Ages, medicine, for it to be effective, was supposed to taste bad. The Arab Muslim physicians and pharmacologists took an entirely diametrically opposite view,” says Newman.

“Now, isn't that a modern way of looking at things?”

“The most famous dish, which still survives to this day, but not in its exact form, was the Buraniya, which is essentially a fried aubergine dish, designed by and named after Buran, the wife of El Maamun, son of Harun Al Rashid. Presented for the first time at their legendary month-long wedding, we don't know whether she actually cooked it for her husband on their wedding day – but I'd like to think she did. Buraniya has travelled throughout the Muslim world and is still eaten in parts of the Maghreb and Spain today.”

One notable exchange between the Arabs and Europe was through the legendary Ziryab. A prominent musician, poet, and scholar, he was also a culinary expert credited with introducing new techniques, ingredients, and table manners to the royal courts of Andalusia.

Some of his most notable contributions include the introduction of the three-course meal, which became the standard for formal dining, and the use of asparagus, sugar and almond milk - as a substitute for animal milk. Marzipan, originally from the Arabic word mauthaban, means 'a king who remains at home and never goes off to war'.

“There is no mention of specific cookery books that Ziryab brought with him, however, I believe that it is impossible he arrived without them. One of the cookery books he must have brought to Al Andalus is the one by his lord and master, Ibrahim Ibn Al Mahdi, the great gastronome,” says Newman.

“How I wish this man (Ziryab) was still around. I would have loved to cook and speak with him because of his links with Ibn Al Mahdi.”

One dish that travelled as far as England was called Mawmenny made of rice chicken and spices. It appeared in one of the oldest recipe collections in Europe: The Forme of Cury, (The Method of Cooking). The name probably came from ma’mūniyya after the Caliph al-Ma’mūn, and was said to be his favourite dish.

One dish that travelled as far as England was called Mawmenny made of rice chicken and spices. It appeared in one of the oldest recipe collections in Europe - Ma muniyya. By Daniel Newman

But modern Middle Eastern cuisine is only about 500 years old, as many of today’s staple ingredients and common techniques, like stuffing vegetables, are absent from medieval Arabic recipe collections. The 16th century Colombian Exchange introduced tomatoes from Mexico, which quickly became popular in Arab cuisine. Other important ingredients from Mexico were chilli peppers, corn, potatoes, sweet potatoes and chocolate.

“The mystery in medieval culinary literature is that it stops in the 15th century, probably a result of Ottoman rule. We have no sources up until the 19th century when cookery books once again appear for the elite, but this time they’re completely westernized. Inspired by French cuisine, they have hardly any Arab elements as modernity came to be equated with being Western, and that included food.”

A bite of food can have profound nostalgic effects, transporting us back in time with each morsel. Recording those experiences allows us to taste centuries-old flavors through ingredients and cooking techniques that have stood the test of time. Food and cooking are worthy of serious study because they represent one of the unique through-lines that tell the story of the history of human society through one of the most intimate and yet social activities: eating.

Marzipan, originally from the Arabic word mauthaban, means 'a king who remains at home and never goes off to war'. - By Daniel Newman