Traveling to sacred and forbidden lands

Map of the world centered on the Arabian Gulf, showing seven mosques or minarets. 18th century drawing of a lost 16th century Islamic world map, centered on the Gulf, showing the Great Mosque and Kaaba at Makkah, the Great Mosque at Madinah and five others in Iraq and North Africa. Credit Antiquariat Inlibris.

Makkah, the holiest city of Islam. It is the city in which one finds peace, and serenity – a closeness to God. It is the global hub for the Islamic civilization. And for centuries people en masse en masse have crossed their lands and travelled long and dangerous distances to perform Hajj. To stand in front of the House of God, the Kaaba, and deepen their bond with God through the oneness of the group.

It is a holy experience like no other. It is here that travelers from all around the world meet in one place, and witness the largest single gathering at one time for one purpose. As such, one can imagine the desire world-travelers have to see this with their own eyes, and marvel at Makkah’s powerful moments.

A number of people over hundreds of years were able to document their own journeys as they left their homelands for Hajj. Some were famous travelers, and some were private individuals who kept diaries of their travels.

One of those famous travelers was none other than Ibn Battuta, a Muslim scholar and explorer known for his extensive travels throughout the world. Little do people know that it was his journey to Makkah to perform Hajj that started his historic exploratory adventures.

It was 1325, and right after he finished his studies, Ibn Batutta set out to Makkah alone. He crossed North Africa with a combination of horses and camels, sometimes even on foot. While on the road, he was in the company of strangers from different areas around the continent of Africa and beyond. Once he arrived in Libya, he joined the pilgrim caravan as was (and still is) custom when setting off for Hajj. Ibn Batutta was on the road for eight months, touring Egypt, Palestine and Syria – all while the caravan brought in more and more pilgrims.

Finally, in 1326 he performed Hajj. Initially intending to go back to his home country, Morocco, Ibn Batutta was invigorated and enamored by the idea of travel. The sense of adventure filled his veins, and so for the rest of his life he would travel far and wide, returning to Makkah more than once to start all over again. Ibn Batutta is the most travelled explorer on record, totalling around 117,000 kilometers.

An orientalist and geographer, he had always been fascinated by the Middle East and wished to explore every region of it. He dedicated his time to learn Arabic fluently so that his travels may be easier than those of his peers.

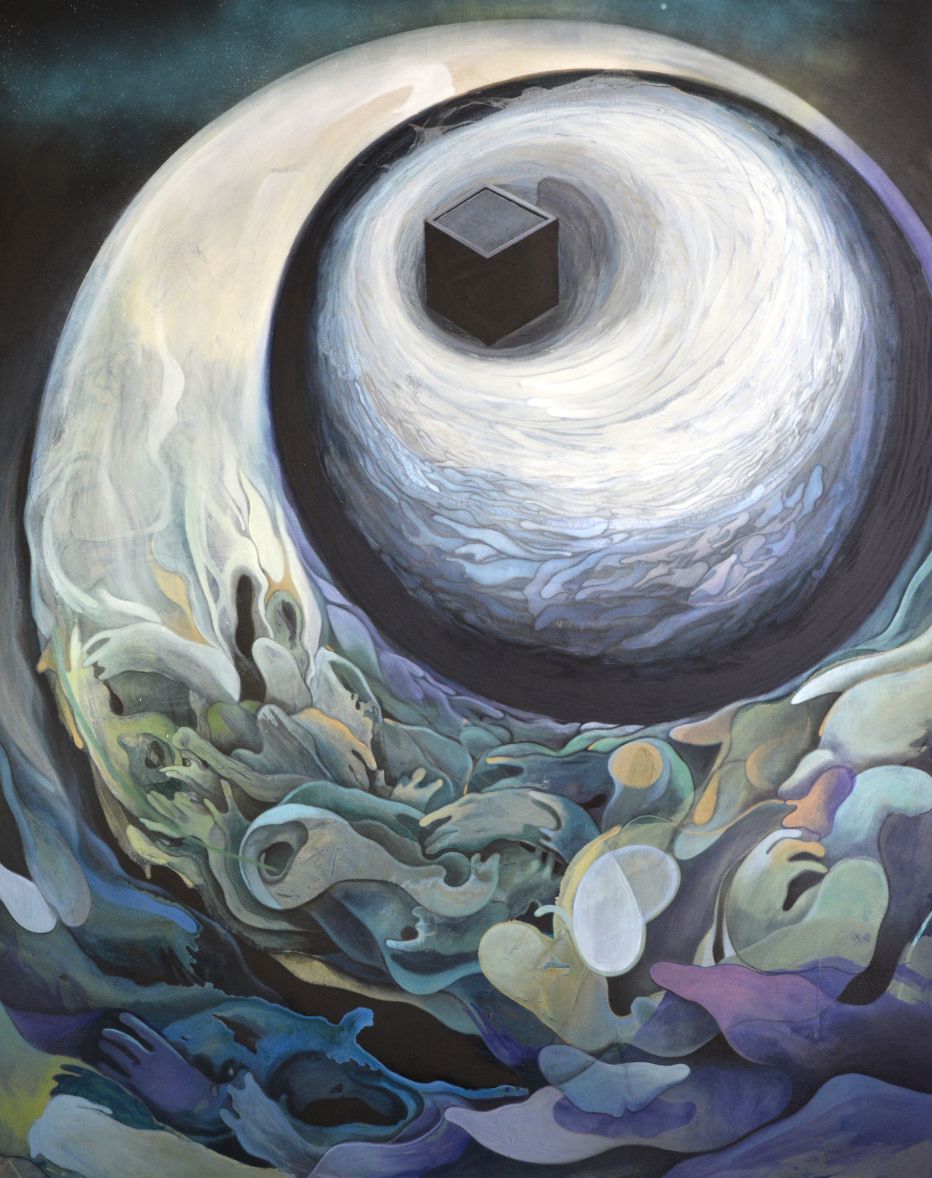

'Al Tawaf Parallel Universe,' by Mohammad Zaza. 2015. Materials: acrylic on canvas. Size: 250 x 200 cm. Courtesy the artist and Hafez Gallery.

Burckhardt had been so dedicated to his work that in 1813 he committed to travelling to Makkah and immersed himself within a caravan of Arabian travelers. To hide his identity and gain access to the holy city, Burckhardt had gone so far as to change his name to Sheikh Ibrahim ibn AbdallahAl-Barakat. Burckhardt was the first European to perform the rituals of Hajj, which at the time was unheard of.

He spent several months in Makkah, writing detailed observations of the city, and of the mannerisms and culture of the locals. For example, in his diaries he wrote, “Makkah may be styled a handsome town: its streets are in general broader than most Eastern cities, the houses lofty and built of stone, and the numerous windows that face the streets give them a more likely and European aspect than those of Egypt and Syria.”

One year later, Wavell made his way to Makkah after he became proficient in both Arabic and Islam. As he was British, he realized the difficulty that lay ahead of him and needed a way to hide his identity. Consequently, he procured fake Turkish passports with his co-travelers, a Syrian named Abul Wahid and a Swahili named Mausaui

All throughout the way, Wavell assumed a Muslim guise. He shaved his head, discarded all of his Western clothing in Beirut and observed Ramadan in Damascus. Luckily while he was in Syria, the Damascus-Medina pilgrim train had just completed its construction. And so, he was one of the first people who rode the train.

After arriving in Madinah and having witnessed an ongoing battle, Wavell and his companions continued their way to Jeddah, later on setting out for Makkah on camels. It was tiring travel as he had noted in his diaries, but all worthwhile.

And compared to other Western travelers, Wavell was the one of the few who was able enough to convey the emotions of his companions, writing “Makkah is a place hardly belonging in this world, overshadowed by an almost tangible presence of the deity.”

Australian Winifred Stegar was another convert able to convey such emotions. In 1969, she published her autobiography Always Bells: Life with Ali, which she had to re-released as a novel as it contained many inaccuracies. However, her writings are interesting enough to include as she was able to keep readers on their feet and pique their interest in the Hajj.

Stegar claimed in her autobiography that she was born in China and abandoned by her parents only to be raised in a convent. Immersed in religion, she had always been deeply interested in the rituals of pilgrimage, and at the age of 19, she experienced her first pilgrimage by trekking through a mountain to a Buddhist monastery of lamas with the help of another English woman, a devotee of Tibetan Buddhism. After this eye-opening experience, Stegar went back to Beijing with an open mind and heart.

She fell in love with her husband Ali, a Hindi Muslim whom she met while working at a silk factory following her return to Beijing. Inspire of the refusal of Ali’s family, nonetheless they married and moved to Australia to start their life together.

One night and after many years and three children, Ali brought up his desire to perform Hajj. He had told her that maybe it was for the best if she stayed behind with the children in Australia. Refusing, Stegar insisted on coming with the children. She was adamant that they were not to be separated. Ali finally gave in and agreed for her to join.

In 1927, the family travelled from Australia to India, and then to the Red Sea by ship, ultimately arriving in Jeddah. From there on, they rode on camels until they were close to Makkah.

She wrote, “We were told that we were close to the holy city, but that we could not go in till morning. The news ran through our hosts like a wild breeze, then an awesome silence fell on each pilgrim paused to realize the great fact. They seemed to all but hold their breath. The silence was broken then by a concerted shout of “Labayk!” It is an all-encompassing word of praise and gratitude and submission to the divine will.”

Another who wrote about their overwhelming experience in Makkah is Malik El-Shabazz, better known to the world as Malcom X. It was while performing Hajj that El-Shabazz’ eyes were open to the world. There, his heart softened, and his life ultimately turned around. He had witnessed the beauty of Makkah, and the impression that it left on him was so deep that he wrote,

“Never have I witnessed such sincere hospitality and the overwhelming spirit of true brotherhood as is practiced by people of all colors and races here in this ancient Holy Land, the home of Abraham, Muhammad and all the other prophets of the Holy Scriptures. For the past week, I have been utterly speechless and spellbound by the graciousness I see displayed all around me by people of all colors.”

With all that has been written before about travelers’ experiences and their deep connections to Makkah, it can be clearly seen how the hub of a civilization can bring so much wonder and fascination into one’s life – how travel inspires and changes everyone who dares to do it, who dares to see the world in another light. To be encompassed and enchanted by the magnificence of unity.

Ghada Al-Muhanna is a Saudi writer, Media and Communications officer at the Saudi embassy in Berlin, and an advisor to the Diriyah Gate cultural project.