Stories of Sand

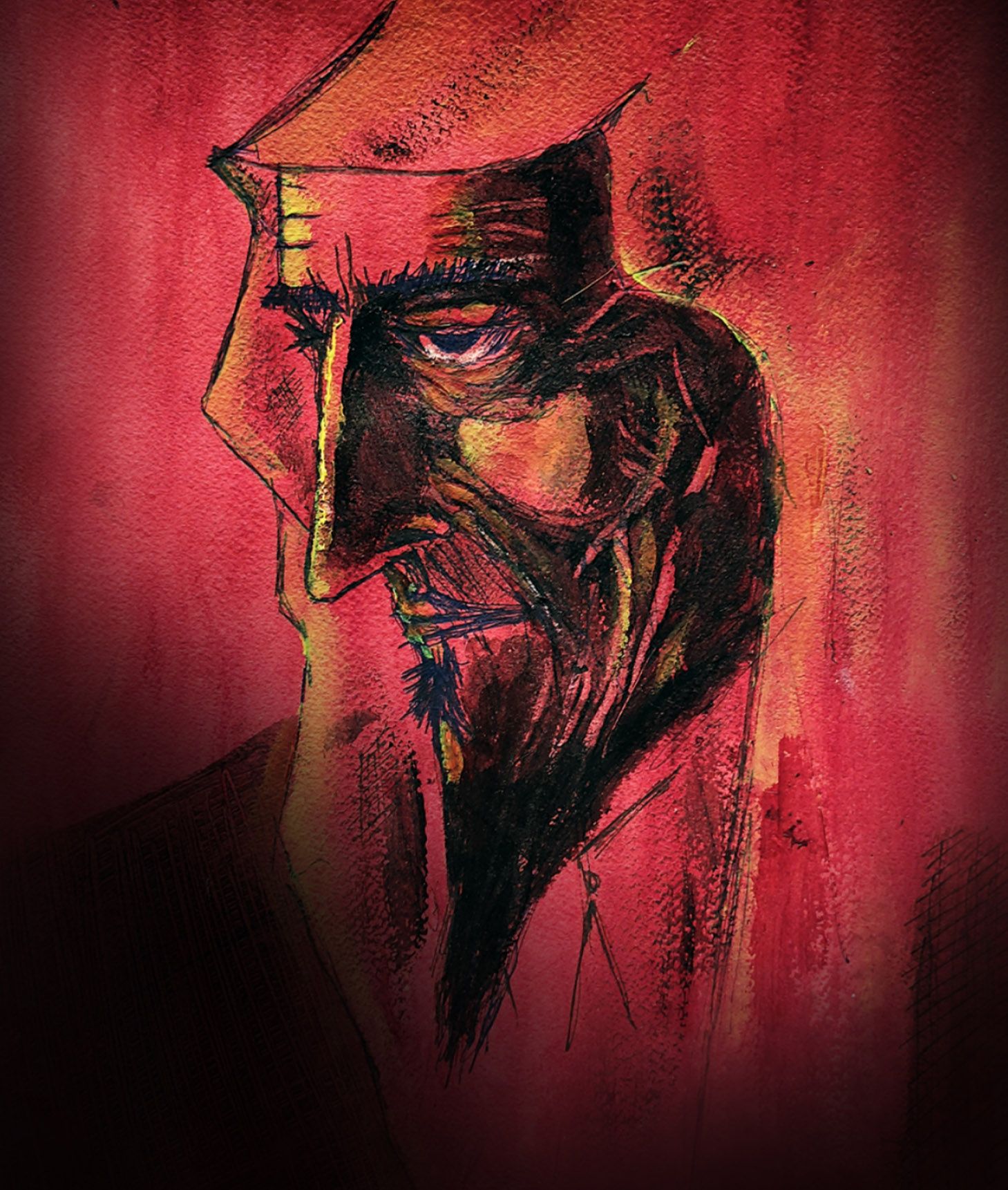

‘Reading the sand,’ by Muhannad Shono. Ink on print, 2021.

Who, while on a training mission above the Rub’ al Khali, reported seeing structures resting within the sea of dunes below.

But when he flew above those same coordinates the following day, the structures were gone, the sand had folded over them like the paper of a book reclaiming the narrative it held. I wonder what words - if any - he would have given to those structures he saw. The sand thus chooses what stories to tell and what secrets will remain a myth. A cycle of revelation then forgetting, reforming the future as it sweeps over the past. Whenever I try to imagine what structures that pilot must have seen, I find myself unable to give them a defined form.

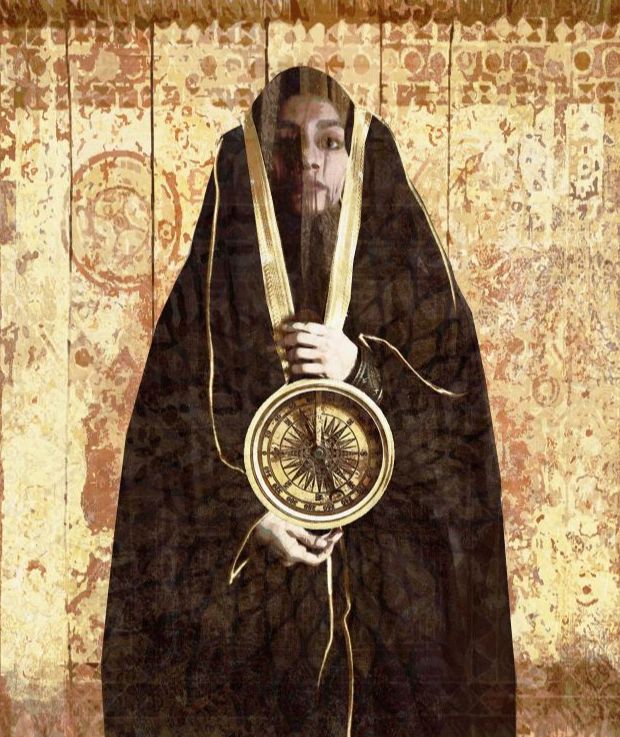

Muhannad Shono. Picture credit Marwah Almugait

I would instead imagine them constantly changing, shifting like the displacement of grains of sand. In 1932, Jack Philby — a British Arabist, explorer, writer, and colonial officer — was searching for a city named Ubar, that was said to be sunken beneath the dunes of the Empty Quarter. The city is mentioned in the Qur’an as ‘Iram of the pillars,’ which Philby transliterated to the city of Wabar.

Philby had heard of a Bedouin legend of an area called Al Hadida (place of iron) where a piece of iron the size of a camel was found. After a month’s journey, Philby arrived at an area about a half a square kilometer in size filled with chunks of black iron rock. It was only after bringing back samples to the UK that the site was identified as that of a meteorite impact.

‘The book of sand,’ by Muhannad Shono. Ink on print, 2021.

“A volcano in the midst of the Rub'al Khali! And below me, as I stood on that hill-top transfixed, lay the twin craters, whose black walls stood up gauntly above the encroaching sand like the battlements and bastions of some great castle. These craters were respectively about 100 and 50 yards in diameter, sunken in the middle but half choked with sand, while inside and outside their walls lay what I took to be lava in great circles where it seemed to have flowed out from the fiery furnace. Further examination revealed the fact that there were three similar craters close by, though these were surmounted by hills of sand and recognizable only by reason of the fringe of blackened slag round their edges.” Might this lost city of Iram, the city of pillars, once built by the descendants of Ad, be the lost city of Atlantis?

‘Reading the sand,’ by Muhannad Shono. Ink on print, 2021.

‘Reading the sand,’ by Muhannad Shono. Ink on print, 2021.

‘Reading the sand,’ by Muhannad Shono. Ink on print, 2021.

Not sunken beneath an ocean, but submerged as a result of a prehistoric meteor impact by a sea of sand. To read the sunken stories of the sand is to go beyond the archaeological definitions of temple and dwelling, tool and pillar.

A true reading is a reading of the shifting sand which has been embracing and giving shelter to those artifacts for centuries past, sand that reminds us of our unread stories, of who we are and where we shall return to. In archeology before the removal of discovered artifacts, the sand is swept aside, the objects are then dislodged from their natural context — rendering the historical landscape illegible — the sand that once held those narratives displaced.

These volumes of swept away sand are our lost pages to forgotten books of sand. I find myself today constantly visited by grains of sand that have traveled across the dunes towards my urban dwelling, storm after storm, meteorite impact after impact, they gather around and within my studio in Riyadh carrying with themnarratives from a place and time far away.