The Feminine Golden Threads

‘Imra'a (Lady)’ by Widad Al-Orfali. 1964. Oil on canvas, 60 x 50 cm. Image courtesy of Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah.

This Iraqi saying is always what pops into my mind when I think of the women in my life and my female ancestry. It is a way to fondly remember what my late paternal grandmother used to say to me as well as to remind myself how important we are as women. Furthermore, I grew up surrounded by golden themes and have always loved gold as a material, color, and concept. Gold may be considered a shiny yellow-ish metal but it is also the feeling of value and importance. Gold to me is my grandmother’s stories, my father’s heart, my sibling’s teasing, my mother’s hugs, the art collection I grew up with, the desert and the dates, our traditional clothes and jewelry, the rays of sunlight, and knowledge acquired and developed.

Furthermore, the women in my life have taught me so much and I always look to them for guidance. There is the Iraqi side of my life with artistic and cultural lessons, which included classic sayings all the way to the Mesopotamian era. The Saudi side of my life taught me resilience, growth, and adaptation, including accepting who you can become beyond the limits of what is expected.

Combining these two elements, Gold and Women, triggered the image of the Woman in Gold by Klimt. The artwork is beautiful and inspires a great level of adoration and awe. However, its story of loss and recovery is one that inspires me. Adele Bloch-Bauer, the woman portrayed in the painting, died early in her life and the family only had this image of her left. After the cultural looting of Austria during World War II, her family no longer had access to the painting and thought they would never see it again until 1998 and the restitution law for looted cultural items was in place. Maria Altmann fought hard to get the portrait back and preserve the history of not only a golden piece of heritage and art, but of her family and her female ancestors, keeping their memory and story alive. Although Klimt is a family favorite and his golden techniques are out of this world, it is Altmann’s story that inspired the choice of honoring these Golden Women: Widad Al-Orfali and Manal Al-Dowayan.

Widad Al-Orfali is an Iraqi artist in her 90s who has contributed to the development of the Iraqi art scene and has one of the most renowned galleries in Amman, Jordan. Her work was introduced to me through my mother and grandmother. She is part of my art education and the canon of what is considered art from my childhood. Her Floating Baghdad or Crescents of Victory series were an inspiration for me at multiple levels: from how I imagined Hogwarts from Harry Potter’s series of books to look like before the movies, to how I designed in my architecture classes during my two year stint, all the way to how I view beauty in art today. Due to her advanced age, this part of the piece will be a combination of a retrospective and a conversation with her daughter, exploring what has been learned and passed down.

Speaking of female influencers, Manal Al-Dowayan is one of the most influential artists in my adulthood, reshaping what is art in my repertoire and understanding, especially what is contemporary in art. Her artwork is always a surprise, threading through it a sense of continuation and wonder. Every piece of her creation has a sense of experimentation, forethought, and research. This is especially true with her work addressing the female experience from her works of Light to Esmi - My Name, including the Tree of Guardians. The meticulous work and effort behind her work as well as the expansion of her projects into veritable mammoths is just an example of how much commitment and creativity Manal exhibits in her work. It is no wonder then that people feel ‘seen’ in her work, which is what will be explored in this piece.

To Khala Widad,

Like how you called my grandmother colorful, I hope I do your colorful story justice.

“Art is my life, my future, and myself” is what Abbasa Al-Azzawi was able to get from her mother, Widad Al-Orfali, at 93 years old. Art has always been a part of who she was and it was her passion from a very young age. She used to draw on whatever material she could get her hands on. She loved all types of art to the point that she has developed a record of music, written and published a book about her life, and opened her own gallery. Her passion was always palpable and supported by her family, especially her husband and her father.

In her first experience delving into the world of art, she had presented her drawings on records to her professor Dr. Khaled Al-Jader, who ended up just breaking all of them. She went crying to her father who told her that should just motivate her more. She shouldn’t chase those who make her laugh because those who make her cry will end up emboldening her to improve her skills. Her father proved to be her first supporter by encouraging her to continue her formal studies.

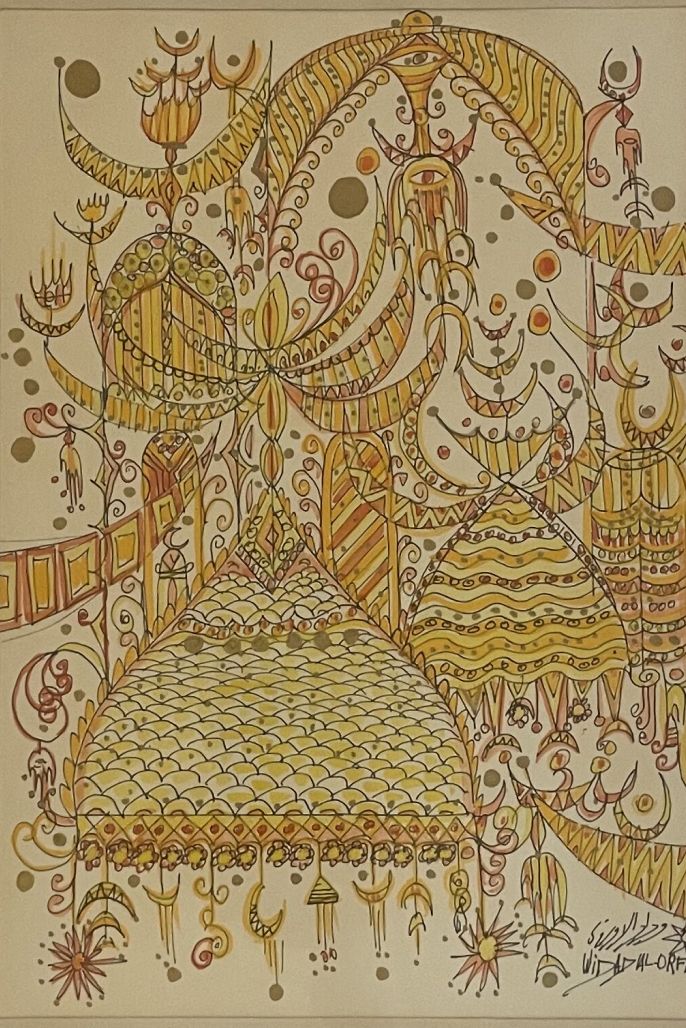

Untitled Artwork by Widad Al-Orfali, Courtesy of the Al-Khudairi and Abbas Family.

Her second biggest supporter was her husband Hamid Al-Azzawi. During her stay in Andalus, and after three years of not producing any work, Al-Orfali was inspired by the high number of details in the aesthetics of the buildings. Her husband, who was a big fan of her work, ran out and got her a box of gold colors; it was the start of her golden age. This is the period when her works looked like miniatures and had domes and crescents as the theme.

Although she sees beauty and art in everything she sees, Al-Orfali is constantly influenced by small, detailed ornamentations in religious buildings as well as general Islamic aesthetics. The colors she chooses (including gold) are in direct relation to Islamic art. Her golden pieces are fantastic and inspirational. “Gold is warmth,” according to her daughter and her work is warm and bright. Color is a major aspect of her art and can be seen to varying degrees in her more recognizable pieces. It even connects to the moment her husband bought her those colors, making it a sentimental color, as well as a staple of her work.

Furthermore, Al-Orfali uses her active imagination to push forward her art: exaggerated sizes and upside-down states of being. Her imagination is what leads her as she is constantly thinking about shapes, colors, designs, and pictures, feeding into artistry and creative output. All her projects start off as mini dreams, then grow and develop as she becomes more convinced about them. The dreams start becoming more detailed until she calls it a project. She sometimes has multiple projects at the same time, taking shape at different speeds.

Her children are avid supporters of her art. Al-Orfali has three children, Abbasa, Abbas and Haila. I managed to sit with Abbasa and hear her talk about her mother. She expressed how she “opened her eyes in an artistic home” and that she supported all her kids' passions, even if none of them actually developed it as a profession. In turn, they supported her by responding to her requests for criticism. They would give her harsh comments; the only way kids could. As they grew older, they developed a different perspective. Abbasa expressed that “her art feels like a dream and it takes me to a place of quiet and serenity.”

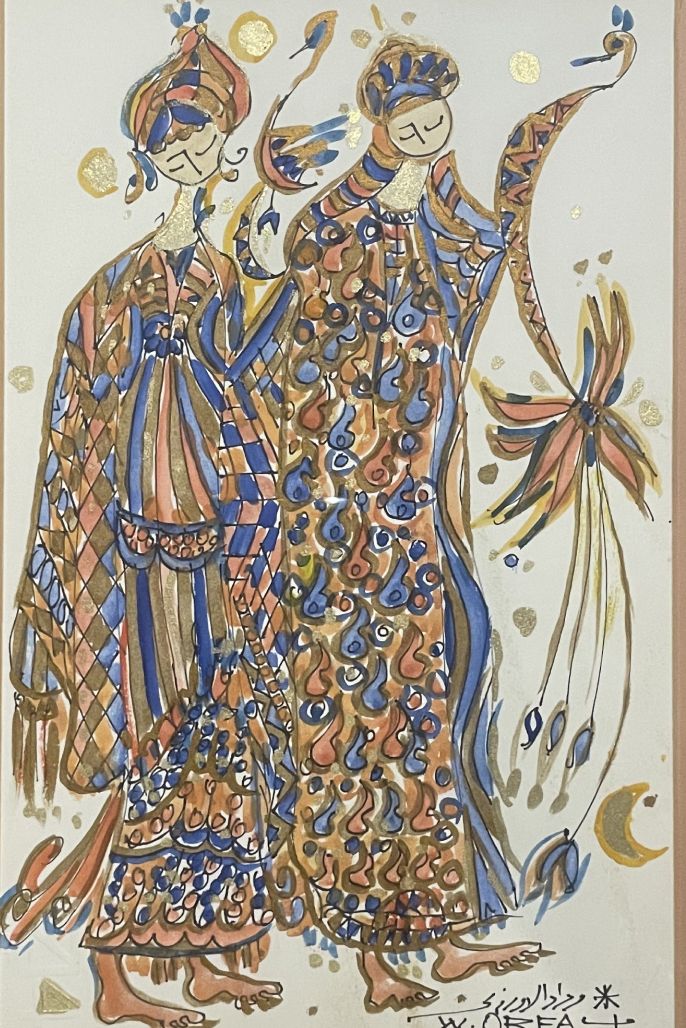

Untitled Artwork by Widad Alorfali, Courtesy of the Al-Khudairi and Abbas Family.

Untitled Artwork by Widad Alorfali, Courtesy of the Al-Khudairi and Abbas Family.

Untitled Artwork by Widad Alorfali, Courtesy of the Al-Khudairi and Abbas Family.

The connection I have with her work is ancestral, magical, and palpable. My imagination is rampant and one of the reasons is her work. I used to imagine her paintings as literal lands of magic and I wished to be absorbed into the actual work and be part of that universe. Yet, what is important to me is the connection I have with the artist through my grandmother and my love for her. My image of her is wrapped in my memories of hanging out with my maternal line and observing her work and learning more about art through these moments. The spirit of her work exists within those moments and has inspired me throughout my life.

Al-Orfali has also inspired her contemporaries and aspiring artists. Her gallery was a space open to all artists whether they were professional or amateurs. She broke down the space into three galleries: contemporary, realism, and calligraphy. She would even take down her own works whenever there was a need for space for another artist’s works. Yet no one can copy her work. According to Abbasa, artists can “mimic her work but can never create the same work, as she draws very chaotically.”

Yet Al-Orfali was never business-oriented and never documented her artworks well. There were many moments when she would participate in international exhibitions only to never see her pieces again because of the disregard for art from the Arab World. She started to pull her work or not present them at all by using the excuse that she doesn’t want to be immortalized for her work. Still, her children want her to be immortalized and Abbasa says “she gave life as much as she could and accomplished so many things all the time.” She had an amazing presence and energy and would say (as stated in her book), “Nobody knows what tomorrow may bring, only a fool could tell”.

She would work hard day and night to produce the work she has, ensuring her immortalization through her works whether she meant to or not.

We would like to thank Abbasa for her time as well as the Orfali Gallery for providing a copy of Sawalif by Widad Al-Orfali.

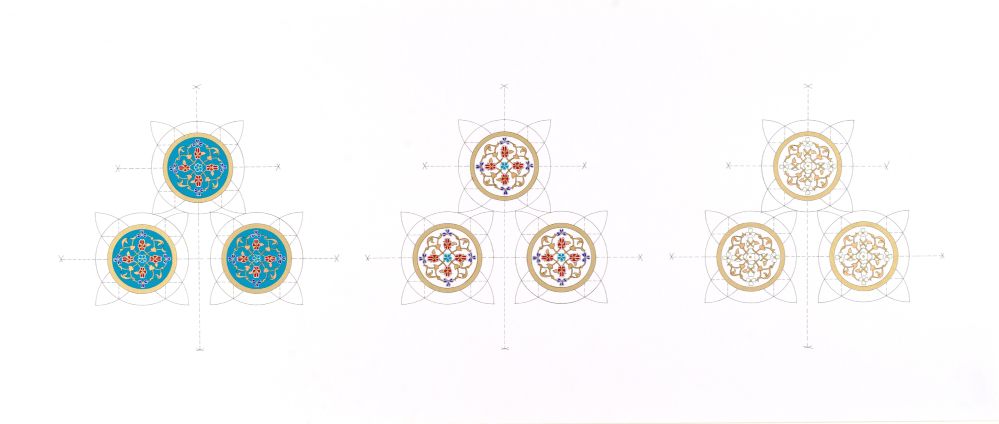

A collection of Widad Alorfali and other various artists’ work courtesy of the Al-Khudairi and Abbas Family

To simply call Manal Al-Dowayan a Saudi artist is a disservice to the impact she has had on the art world nationally and internationally. Her works are regionally and nationally rooted, but they have universal messages of visibility, invisibility and reviving forgotten (or nearly forgotten) stories and communities. Her exploration of what is visible and what isn’t and the power structures surrounding that -- including her experience of being a woman and “not seeing my image; my name not being announced publicly; my voice being silenced” -- is what inspired her artworks.

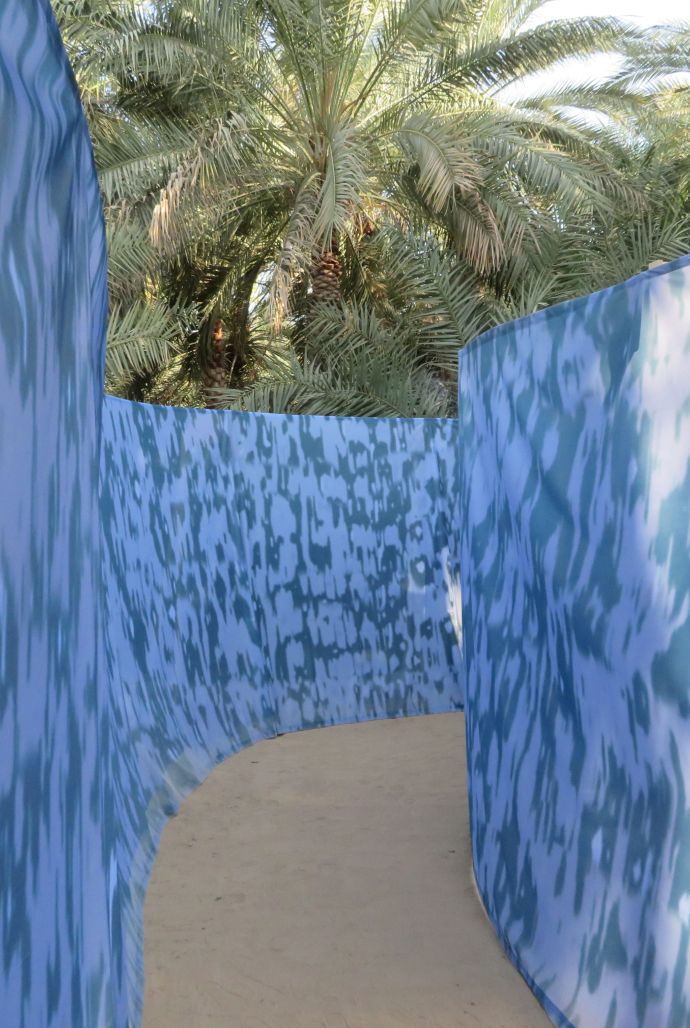

She also has investigated the communities and the people who worked in the oil fields, “building our economy and bringing out the black gold for us.” Her work extends to the invisibility of roots of palm trees in Al-Ain in “You Are From Me And I Am From You,” the invisibility of water supplies in Al-Ula in “Now You See Me, Now You Don’t,” and the invisibility of climate change through the death of coral reefs and their bleaching which is the focus of a current project.

Leaves from “Tree of Guardians” by Manal Al-Dowayan, courtesy of the artist.

Al-Dowayan considers the acts of remembering and forgetting as a continuation of the visibility narrative (what you remember is what is visible and what you don’t is invisible). Her father suffered from Alzheimers and she tried to reclaim his memory through the collections of memories in “If I Forget You, Don't Forget Me.” That period of her practice is influenced by the idea of healing the wounds of loss, the invisibility of a person’s loss, and the visibility of his memory.

“I thank God I had art to heal me.” Healing is an interesting journey. It is never linear and is always easier with an outlet. The work Al-Dowayan produced during this time did exude a melancholic feel, but it wasn’t until she told me the self-healing process these works provided that I understood the nostalgia and the longing in these images. She has brought to life experiences that only she can portray as part of her lived experience and her perception of the world surrounding her existence. She has also created the opportunity for people to see themselves in the artwork.

To add to that experience, all of Al-Dowayan’s artworks are significant to her as they all symbolize a part of her and her development as a person and as an artist. Her “I Am” series was the beginning of her career and her exploration of the idea of visibility. The work that was transformative for her was “Esmi - My Name” because it was a collaborative work in a public space where people were eager to connect and engage in the artwork and the topic explored. The sculptures are a reassessment of softness and the essentials of creation and have become an important part of her practice. Another significant piece is “Now You See Me, Now You Don’t” as it was her first artwork to be permanently installed in a location. Her work has transcended the realm of being just contemporary art into a significant moment of connection between the artist and the audience because they always see a part of her in her works.

Leaves from “Tree of Guardians” by Manal Al-Dowayan, courtesy of the artist.

Sitting with Al-Dowayan virtually while she is in her studio in London and in the midst of researching for a new project is a great honor. It is a moment I recognize as a full circle as the first time I was exposed to her work was in London while I was conducting my master’s research and looking for my identity within my society and community and felt a kinship with her work. I felt seen and understood at a level that I had not experienced before. This experience could feed into what art is to Al-Dowayan: A form of expression and communication.

“My art is very close to who I am and close to my transformation as a woman from a young adult to a middle-aged artist. As I grow older, the conversations that I care about change and the mediums are changing too.”

With her dynamic and diverse history,

Al-Dowayan’s love for art translated into her ever-changing fascination with artists, art movements, and materiality. When asked what artists inspire her, she expressed how it is constantly changing as she journeyed through her practice and there is no specific artist that inspires her, but she did mention many creatives from all over the world and with different practices like Saloua Raouda Choucair, Robert Rauschenberg, and Laurie Anderson.

They all have certain ways of expressing their lived experiences and presenting their concepts through materiality and perspectives. “All artists influence me; it depends on the day and the research I am doing.”

When asked what gold meant to her, she responded that she never used gold and has no specific feelings for it. The Dior bags are the only ones that use actual gold and that is due to the palette of luxury goods rather than a purposeful decision. Some materials give the not purposeful illusion of gold when it is actually brass, like the leaves from Tree of Guardians.

Still, she expressed that “materiality is very important to my practice” and reinforced that message by saying “materiality is at the core of my work, not a reflection of it,” meaning the type of material used is based on what is needed to be expressed and how the material interacts with the larger product. For example, metal is a “rigid” medium while paper or weaving can be considered a “soft” or “fluid” one. The idea is to experiment and play with the materials so that there is space for exploration.

“Tree of Guardians” by Manal Al-Dowayan, courtesy of the artist.

In “Tree of Guardians,” the rigidity exists in the leaves while the softness exists in the papers surrounding it and the act of writing down that female ancestral line that can be both invisible and forgotten. This artwork is an experience of a space that never has existed before with papers filled with drawings of family trees varying in its details, creating space for the viewer to explore the names and see if there are any possible connections, as well as to ponder their own female family tree. In contrast, the leaves are cascading down from the roof at varying heights to represent how far back each woman was able to trace. It’s heartbreaking to see that the majority are shorter as they cannot go back in their family’s collective memory and find the names of their female ancestors. Yet, if you lay down underneath these leaves, you feel a connection to this feminine energy exuding from the efforts these women had gone through to ensure whatever name they had will be documented.

Although Al-Dowayan is interested in female heritage and is working on the research to understand that better, what she has discovered in her work to uncover the invisible and the forgotten is that “women are spaces that store oral histories and storytelling. Although the official histories are written in books, there is an alternative history that exists in stories that mothers and grandmothers tell their daughters and granddaughters. It doesn’t mean that one history is more correct than the other but the two complement each other and complete the story.”

Al-Dowayan here explores the idea of how impactful our female ancestral lines are and the stories we inherit through these moments of exchange and bonding. She goes on to express what she loves about oral histories: “is that there is a lot of imagination, openness, and fluidity” and this matches her artworks because they both allow spaces for flexibility. Based on memory, whatever history we learn is subjective, hence “storytelling is more imaginative and it changes every time it is told and will continue to change.” This artistic way of sharing history is much more interesting to Al-Dowayan than traditional means of preserving heritage because “the truth remains and the core remains,” and what gets added is a new generation of memories.

“Our womanhood and female experiences have allowed us to enter these spaces and it is like having the key to all the rooms of the castle.” Women have the ability to easily enter spaces that are usually private and can engage with subjects and connect with memories that we would not have been able to as outsiders to those spaces.

Listening to Al-Dowayan talk about these memories and oral histories reminds me of how I used to listen to my grandmothers as they told me their version of their histories, stories, and secrets and how important that is to our development as females to have that connection and that space to grow. Our attachment to our female ancestors is very much exemplified by our attachment to our mothers.

Leaves from “Tree of Guardians” by Manal Al-Dowayan, courtesy of the artist.

When asked who is the most influential woman in her life, Al-Dowayan responded “it is always the mother that influences: she either becomes the person you don’t want to be, or she becomes the person you aspire to be, or she remains in the background as the person who made you who you are regardless of the mistakes and the correct paths she has taken.”

Al-Dowayan confessed that her mother is honored in a lot of her art directly or indirectly, but she does not want to feature her since “I fear after dedicating a lot of my art to my father’s memory that I do not want her to be part of this conversation because once I start documenting her that means that I am sort of preparing myself for her departure from this universe.” Her mother was a catalyst, especially in the beginning of her career, since she was the initial source of information for so much of her work and her lines of inquiry, whether it was correct or not.

She did end up creating “You Are From Me And I Am From You” as a love letter to her mother using the palm tree as a symbol of caring and inducing mother nature’s energy into an artwork that gives a sense of belonging. The exploration of the softness in the invisibility of caring and the roots of the palm tree as well as the connection to mother nature as a part of womanhood.

Although the material is at the core of her work, the concepts in her artwork show how she addresses complicated narratives through different topics – from womanhood and femininity, to communities and nature with the idea of visibility and invisibility at the forefront of her practice – which is what makes Manal Al-Dowayan one of the most important and impactful contemporary artists.

“Esmi - My Name” by Manal Al-Dowayan, courtesy of the artist.

Family Trees from “Tree of Guardians” by Manal Al-Dowayan.

“You Are From Me And I Am From You” by Manal Al-Dowayan, courtesy of the artist.

“Now You See Me, Now You Don’t” by Manal Al-Dowayan, courtesy of the artist.

“I Am” by Manal Al-Dowayan, courtesy of the artist.

Dior bag by Manal Al-Dowayan.