Evading the Wound of Time

The Dutch Proverbs (1559) by Pieter Brueghel the Elder — a vivid illustration of 100+ proverbs in one scene. Credit: Wikimedia Commons / Google Art Project.

There is some delight in depicting life in primitive and rural communities as “life beyond time,” but this is a misconception; time leaves its wounds on humanity everywhere – including this idyllic setting.

From the wound of time came belief in resurrection for some, and reincarnation for others. Philosophy was born to provide a form of understanding for the riddle of life. Plato divided life into immortal forms and perishable images. Later came the philosophy of eternal return, rooted in ideas of reincarnation. By contrast, existentialism embraced nothingness with a mournful leaning, tinged with a desire for self-torment, for the outcome of the confrontation is predetermined.

The grief of Gilgamesh over the death of his friend Enkidu reflects that sense of defeat in the face of death.

Time is a wound, and the present is its core of pain; and it reminds us that life is unrecoverable. It is the most real and most strange of tenses, born and dead in a single instant. The future, in contrast, is an imagined time, doubtful in its existence. The past is the most real of times, yet it lies quietly in the archive. We have no power over it, cannot erase it, nor bend its course to suit our desires.

The fleeting succession of the present’s birth and death is both enchanting and terrifying, hence we seek to appease it as primitive humans once appeased evil forces by worshiping them. One way of appeasing time is through writing a novel.

The fear of mortality, shared by writer and reader, is among the most important reasons that make the novel a necessity. The writer lives the lives he writes as extensions of his own, sometimes falling into madness as he hopes for immortality through his work. The reader, meanwhile, dedicates part of his time to a novel with no clear utilitarian gain. It offers no certain knowledge like the natural sciences, yet he reads because it grants him an additional life. He examines the wounds of its characters, distracting himself from his own wound, and spies on others’ mistakes to avoid committing them himself, for his private life is singular, without a chance for repetition or correction.

A novel does not demand that we wait long years to witness its mysteries or learn the fates of its characters. We see a crawling child, and on the next page he is in school, then at university, and later trapped in the snare of an ill-suited marriage. This economy of fictional time is itself a motive for reading.

The strategies of constructing time in the novel are another game of dodging mortality. The simplest temporal structure, and the least dependable, is the linear one that mimics time, carrying the hero from childhood to old age.

But there are structures for elongating and deceiving time. The circular structure is the most capable of deluding death: the novel begins at a point in the past or present, time moves forward or backward, and then returns in the end to its starting point. There is also pendulum time, oscillating between past and present in a movement that distracts the reader’s consciousness. And then there is the chaotic structure, devoid of logic and order. This unruly time appears in surrealism, or in a novelist’s attempt to shape a delirious character, like Benjy in Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury.

Meanwhile the stream-of-consciousness technique manages to stretch time: a fleeting glance out a train window could open into an infinite expanse of memories and feelings, each summoning the next.

Fairy tales and legends of the Middle East. Credit: Shutterstock.

In the masterful narrative book, One Thousand and One Nights, time is extended through various techniques, going beyond the slow, reflective pace of conventional storytelling. Here, it is speech or death, with no third option. Shahrazad’s life is at stake every night; any slackening in the taut string of her storytelling would send her straight to the executioner. The manipulation of time through stories begetting stories was her survival tactic.

One Thousand and One Nights blend past, present, and future like nothing else. The frame story speaks of two brother-kings, Shahryar and Shah Zaman, who lived “once upon a time.” Yet when Shahrazad takes the helm of storytelling, she tells Shahryar tales of two future caliphs, Abd Al Malik Ibn Marwan and Harun Al Rashid, presenting them as kings “from time immemorial”. In their order of appearance, we encounter the Abbasid Harun Al Rashid early on, while we must wait hundreds of nights before meeting the Umayyad Abd Al Malik Ibn Marwan.

In Sinbad’s voyages, we find the circular structure of time: he recounts his seven journeys to friends after retiring, the act of narration itself implying that the storytelling could go on forever.

These miniatures pulse with the spirit of One Thousand and One Nights, where legends and folk tales converge in a single artistic frame. Credit: Shutterstock.

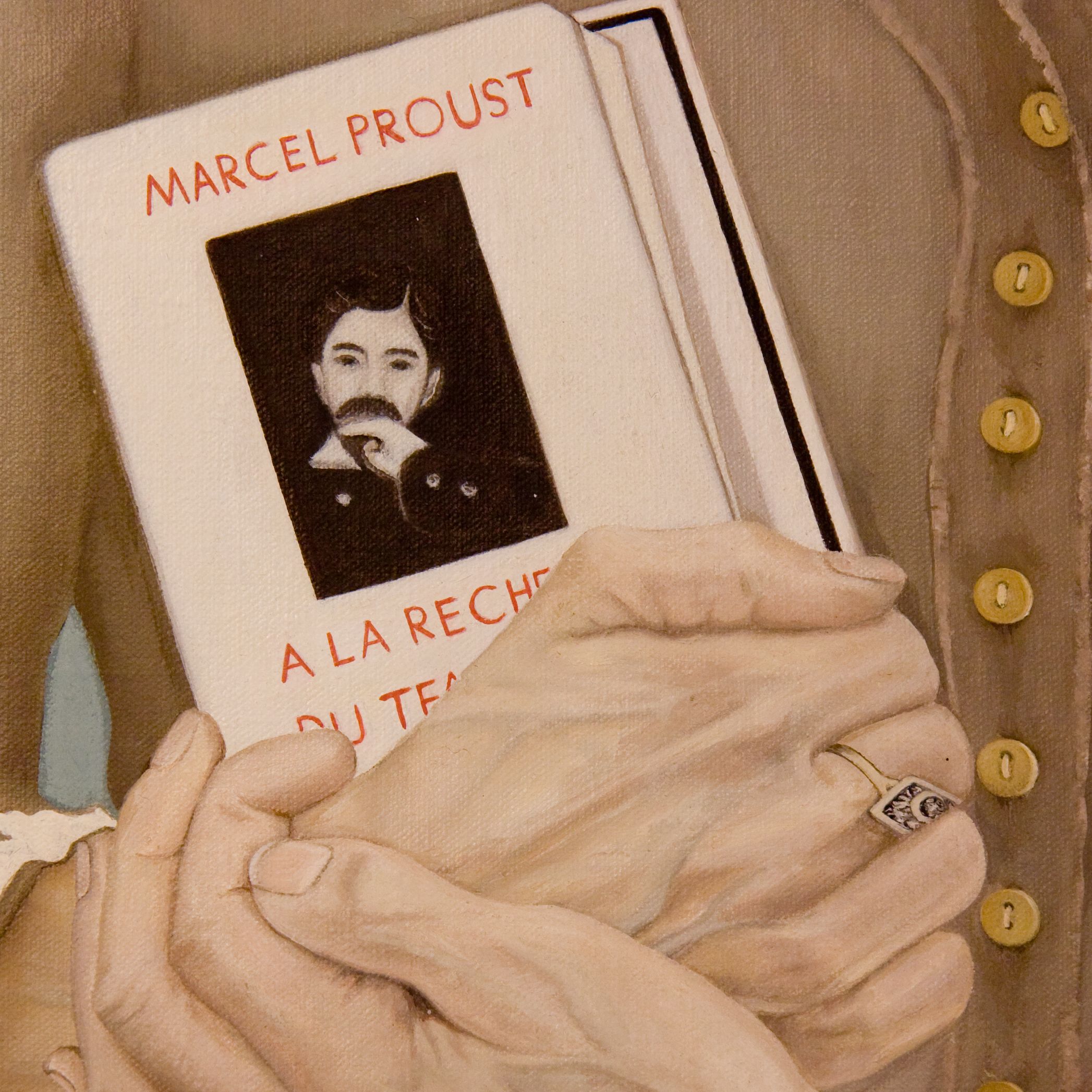

Through In Search of Lost Time, Marcel Proust achieved something similar, creating a labyrinth of times and trapping the reader within the seven volumes of his epic. Still, not every novelist must construct such vast temporal landscapes, for the novel’s art is generous, full of clever strategies and subtle manipulations.

While nothing can fully remedy the ache of passing time, the novel can, at least, alleviate it.

YCE Rouziere by Marcel Oosterwijk. A close-up photograph capturing part of the book cover for In Search of Lost Time by Marcel Proust. credit: Marcel Oosterwijk / Wikimedia Commons.