How Style Mirrors Society Across Time

Gazette du Bon Ton, 1920 – No.7, Croquis Pl. XXXV: Doeuillet (1920) by Fernand Siméon. Credit: Public domain, Artvee.

Time is the most hidden yet influential element in the fashion industry. It is not possible to separate taste from the rhythm of time, for every era remolds beauty according to its social, economic, and political conditions. In this sense, Europe offers a model for studying the relationship between time and fashion, as it possesses a rich archive that clearly documents how wars, economies, and cultural movements have remolded human appearance throughout the 20th century.

In the beginning of the 20th century, European fashion reflected the social hierarchy of the time. Long dresses and corsets defined the body and imposed a fixed image of femininity. But after World War 1, everything changed under the pressure of a new reality that imposed shifting priorities on elegance as women entered the workforce. “Flapper” dresses with straight lines emerged, and the waistline lost its status as the center of beauty. This was an architectural response to centuries of externally-imposed femininity.

The costumes of the 1920s did not offer a clear revolution but rather a transitional experiment redistributing the balance between freedom and structure. Short hairstyles, light fabrics, and practical shoes all signaled that life’s overall tempo was accelerating, and the female image had to adapt. Ornamentation did not disappear but was redirected, as jewelry became lighter and makeup simpler. The 1920s became a testing ground for what femininity could mean in a changing world.

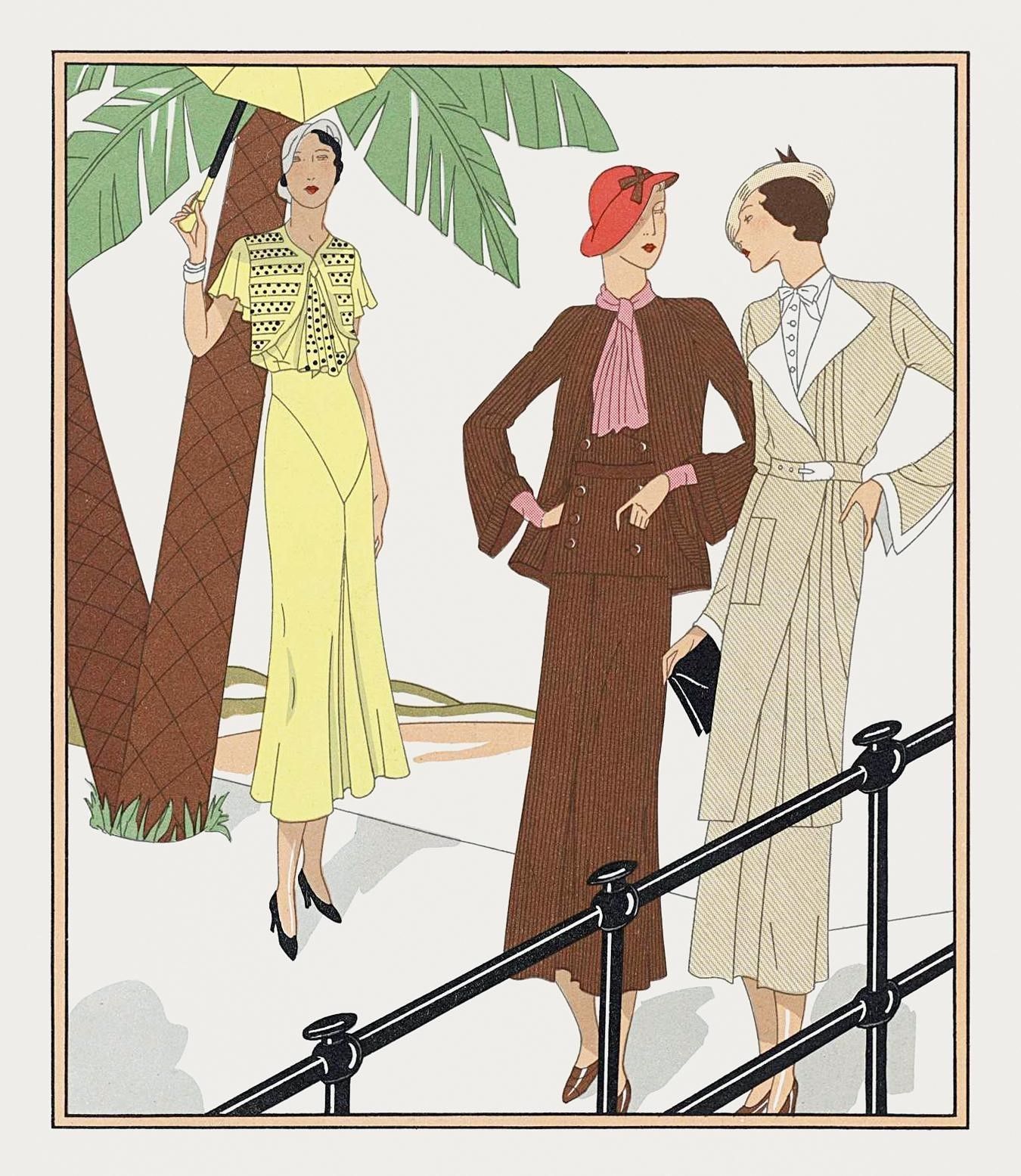

As the 1930s arrived with the Great Depression, fashion changed into more conservative shapes. Curved feminine cuts and simple fabrics reflected a societal desire to restore psychological and economic balance during financial chaos. The 1920s had been about searching for freedom; meanwhile the 1930s were about securing that freedom after the shock of war and economic collapse.

When World War 2 erupted in the 1940s, austerity was imposed on the fashion industry. Factories were devoted to military production, and clothes became utilitarian, resembling uniforms. Elegance became a luxury. Yet after the war ended, society sought aesthetic and emotional compensation. In 1947, Christian Dior introduced his famous “New Look” collection, with narrow waists and full skirts as a declaration of a return to normalcy and economic prosperity. This was the beginning of an era in which fashion relied on material luxury as a symbol of recovery.

The 1960s were a major turning point in fashion’s relationship with time. The youth became an economic and cultural force that could define public taste. Miniskirts, bold colors, and synthetic fabrics symbolized modernity and equality across gender and class. Fashion became a way to express oneself politically and socially.

In the 1970s, the general mood transformed towards simplicity and nature with the rise of the hippie and bohemian movements. Cotton, earthy tones, and patterns inspired by Eastern cultures. This shift was a direct result of collective fatigue from rapid consumption and Western centrality, alongside a longing for a slower pace of life.

In the 1980s, Women entered professional and managerial positions in force, and “power dressing” emerged as a reflection of corporate culture. Suits with broad shoulders symbolized authority and confidence in a competitive work environment. Fashion became a language of power and economy, an emblem of career success and individual achievement.

Women’s clothing (1932) fashion illustration by Maggy Rouff. Credit: Public Domain Review, Rawpixel.

In the 1990s, fashion got turned upside down as “grunge fashion” became the norm. Simple, worn-out clothes, neutral colors, and a preference for comfort over form. After a decade of extravagance, honest simplicity became the new form of self-expression. Fashion here represented “a withdrawal from pretense”.

With the new millennium, the concept of time in fashion changed entirely as fast fashion emerged and compressed the fashion cycle from seasons to weeks. The market began to rely on constant change. The relation between consumer and clothing shifted from possession to consumption as the goal was no longer to own an item but to display it, then replace it. Socially, repeating an outfit became almost unacceptable, especially with the rise of social media that made form and image more important than function. Purchasing rates and production sky rocketed, and so did the profits of major brands and environmental waste. Naturally, the expected counterculture emerged in the form of “slow fashion”, advocating moderation, fabric longevity, ethical sourcing, and fairness. This movement put the focus of value on sustainability and quality.

European fashion history provides a model on how fashion can mirror collective consciousness and emotion. Clothing reveals social structures, economic conditions and cultural shifts. From workwear to celebration gowns, and corsets to practical cuts, dress has always been a silent language expressing human thought.

Studying fashion is an act of reading collective memory, a record of humanity’s interaction with time. Fashion is an archive of the evolution of tastes and values.

Women in 1920s fashion. Credit: Public Domain Pictures.

* Wejdan Almalki is a writer specializing in fashion and the founder of Mansooj, a Saudi platform that enriches fashion knowledge.