Making Sense of Time

Calligrapher Farrukh ibn `Abd al-Latif, Image from Metropolitan Museum.

The first human timepieces were the sundials and water clocks that began to appear around 3,500 years ago. But long before that, as many as 40,000 years ago, humans carved lines into what historians call “calendar bones” in an effort to mark time. Thousands of years before the written word, people organized the stories of their lives around units of time.

Recently, we humans have found ourselves using ever-smaller units of time. From our ancestors’ use of the seasons and the phases of the moon, we have shifted to increasing precision. Scientists now employ units as brief as the “zeptosecond,” which is the one sextillionth of a second it takes for a photon to cross a hydrogen molecule.

Yet timekeeping is never just about science. It remains story-based, as Rebecca Struthers observes in her award-winning work of memoir and history, Hands of Time. We still talk about life “before Covid” and “after Covid,” and we also mark time by personal events, telling children, “That happened before you were born.” Indeed, all the books below—whether histories, novels, or scientific works—use stories and storytelling in order to help us make sense of time.

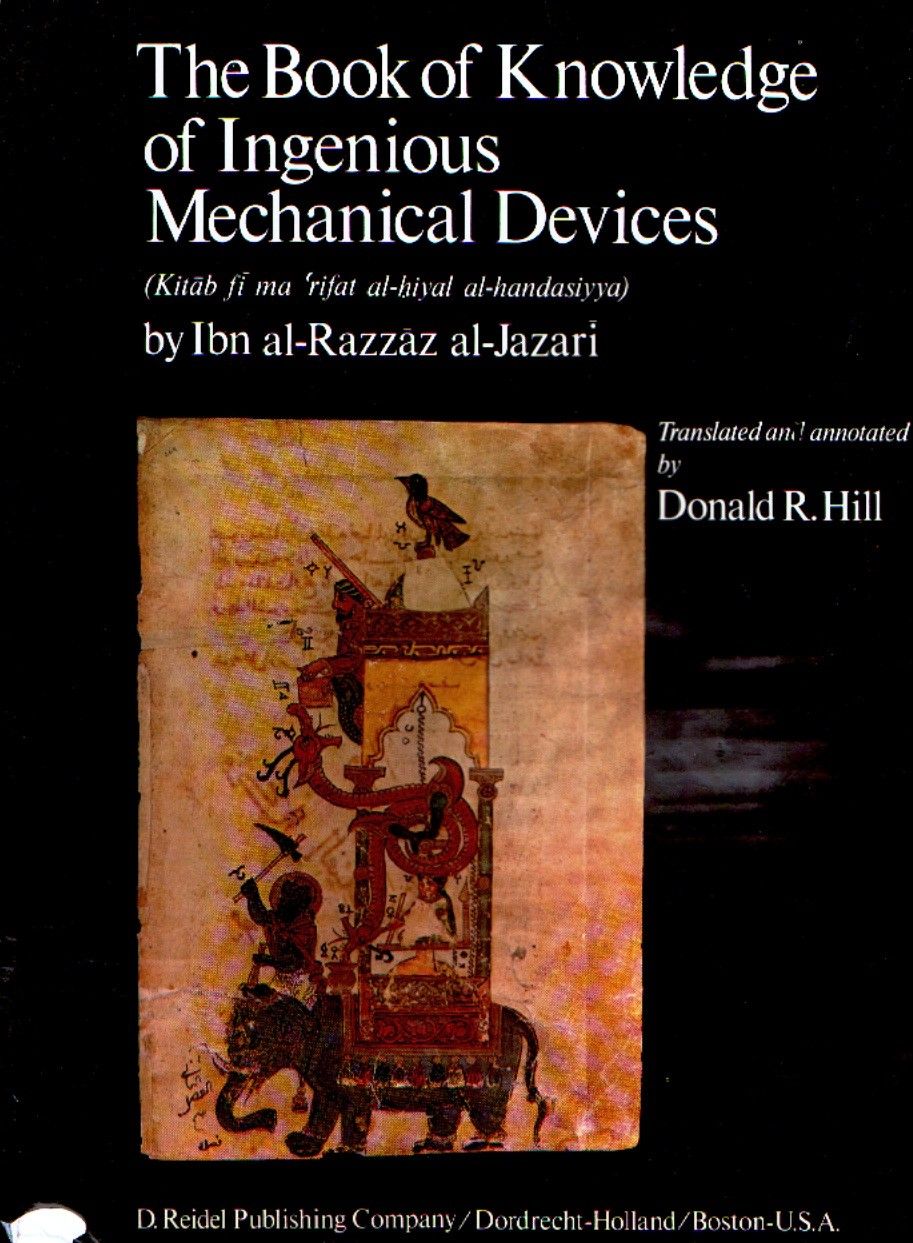

If you’re interested in early clocks, this thirteenth-century work by Ibn al-Razzaz al-Jazari (1136-1206) will give you an exciting glimpse of medieval timepieces, both real and imagined. Al-Jazari was a scholar, inventor, engineer, artist, and mathematician, and he details the workings of many incredible time-keeping devices.

These include devices such as “the castle water clock,” “the water clock of the drummers,” “the water clock of the boat,” “the water clock of the peacocks,” and what is perhaps his most famous invention: “the elephant clock,” pictured here.

The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices, by Ibn al-Razzaz al-Jazari, translated by Donald R. Hill.

It is easy to imagine twenty-first-century watchmaker Rebecca Struthers enjoying the company of twelfth- and thirteenth-century clockmaker Ibn al-Razzaz al-Jazari.

In her Hands of Time, Struthers takes us on a journey across the history of timekeeping through the lens of a highly skilled craftsperson.

She not only walks us through the fascinating range of premodern timepieces, but also how these clocks and watches were adapted to fit the needs of different societies and cultures, and even changed them.

Hands of Time: A Watchmaker's History, Rebecca Struthers

This play, by the great Egyptian author Tawfiq al-Hakim (1898-1987), is based on what is relayed in Surah al-Kahf of the Qur’an.

In it, a group of believers take refuge in a cave. When they emerge, they believe it has only been a day later, when in fact 300 years have passed.

In al-Hakim’s play, two courtiers, a shepherd, and a dog take refuge in a cave during an era when Christians are persecuted. When they awake three hundred years later, Christianity has triumphed.

Yet their family and friends are dead, and they are no longer treated as people, but as saints and legends.

Although audiences didn’t enjoy this meditation on time when it was put on stage, it makes an excellent and thoughtful read.

People of the Cave, Tawfiq al-Hakim, translated by Mamoud el-Lozy

Even though the English title suggests this will be a work of science fiction, there are no time machines or futuristic devices in Shalaby’s novel. Instead, like Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, it is an entanglement of present and past.

Yet here, progress is a lot more fickle. Even though the Egyptian pickles and sweets seller carries twentieth-century technology back through time, he finds himself unable to impress a twelfth-century caliph—especially when his batteries run out.

A charming meditation on the arc of history and the things that stay the same.

Time Travels of the Pickles and Sweets Vendor, Khairy Shalaby, translated by Michael Cooperson

One thing that contemporary mathematicians and storytellers agree on is that time is relative. But how did we reach this conclusion about time’s relativity?

Harvard scientist Peter Galison tells the tale of how clocks, trains, maps, and telegraphs underpinned Albert Einstein’s and Henri Poincaré’s great twentieth-century discoveries, and how these changes in our understanding of time and place affect our lives today.

Einstein’s Clocks, Poincaré’s Maps, Peter Galison

In some ways, time is outside us. We glance down at our phones, we look up at clocks, and we move between different “zones” of time. But in this book, neuroscientist Dean Buomomano explores how time works inside us. Boumomano must first pull apart the many different things we mean when we say “time.”

Then he asks: How do our brains process and keep track of time? Why is time so important to us? What does it mean for time to “pass” or “flow”? And critically: How does the human brain create time?

To discover other creative literary works from ArabLit Quarterly, check out their FOLK issue.

To enjoy the borderless world of books, please visit Ithra library and the Arablit website.

Your Brain Is a Time Machine, Dean Buonomano