Photography: Resisting the Dissolution of Time

Jeddah, Al-Balad 2016, courtesy of Abdullah Almalki.

When humanity discovered that it could capture light, and thus freeze time, everything changed. That discovery showed that memory, alone, was insufficient to preserve fragments of faces, places and moments. The camera became a parallel memory that could arrest moments in time and tell them anew.

The lens gives us a modest amount of power over what we cannot possess, the moment and the transient. Susan Sontag says in her book On Photography “To photograph is to appropriate the thing photographed.”

On the other hand, Dorothea Lange saw photography as more than documentation, as an act of resistance against disappearance and dissolution in this world. She said, “Photography takes an instance out of time, altering by holding it still.”

On the edge between existence and nothingness, between what was and what will never be, a photograph stays. As Roland Barthes described it, “… the photograph mechanically repeats what can never be repeated existentially.”

Photographers’ perspectives on the world and their choices of what to capture are more than observation, they are the recreation of the moments themselves. And thus, photography’s definition swings like a pendulum between creation, possession, and resistance; between the now and the fear of its passing.

Within this space, between light and memory, we interview photographer Abdullah Almalki, about his relationship with camera and time, on the moments he was able to cease, and those that faded away before he could capture them.

I was five or six years old when I held a camera for the first time. My father owned it and it had a distinct red color. My childish curiosity led me to hold it, and I wondered how such a small red object could capture my smile?

By then, I experienced every stage of photography with my father. Shooting pictures was something we would do during our family gatherings or outings. Later he would take me to the photo lab to develop the film. I used to think that developing (tahmeed) the film meant squeezing a lemon over it.

I grew up, but that child who believed that film was developed with a lemon did not grow up. I bought my first camera when I was twenty years old, but it was completely digital. From the very first moment, a relationship arose that might seem strange from afar, but to me, it was completely natural. I used to carry my camera with me everywhere. It was like my third eye. Even when I slept, I would literally place it beside me. The first thing I would do upon waking was look at it and touch it.

I started photographing everything I saw in front of me, but after many experiments that lasted about two years, I found something magical in photographing people’s faces and documenting their lives and stories. At that point, my relationship with the camera changed. Every picture became a source of a different story.

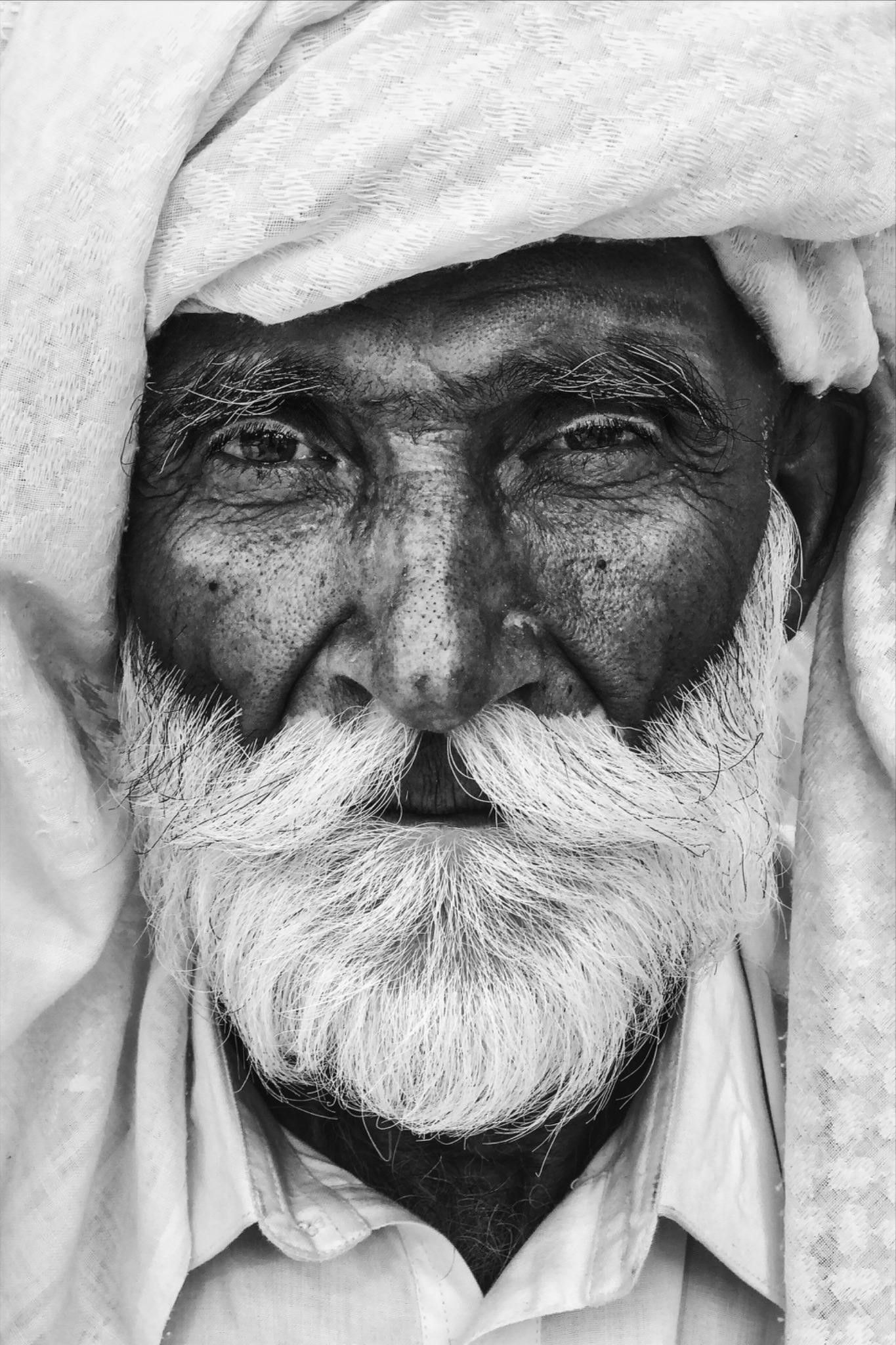

“As the day he was born.” Makkah, Mataf Courtyard 2014, courtesy of Abdullah Almalki.

You pause in every photograph, but between every photograph, there is space for movement. Movement changes continuously after every pause or after every photograph.

The photograph, in its many forms, carries contradiction. Sometimes an antidote against forgetting. Sometimes a curse that cannot be gotten rid of, imprinted in memory.

Time is sensed in the photos of people through the contour of their faces, their eyes, and the subtle details in between.

For me, a photo’s worth is in what happened before and during it. In the story, and the relationship between the photography and the owner of the story. In the relationship between the photographer and his camera.

Pilgrim Saida, Makkah 2018, courtesy of Abdullah Almalki.

I think that the personal relationship that forms between me and the people I photograph is the secret. The personal relationship was always the priority and the foundation; the photograph came later. This relationship allows the person in front of you to open up and tell their story, and listening to this story carefully, understanding it and absorbing its details makes the picture more real.

Documentation acts as a secondary memory, a space we can return to in order to appreciate its beauty, contemplate it, and learn from it.

Cities like Makkah and Madinah. They are the cities which people come for pilgrimage from every distant place. You hear all languages and dialects. You see all ethnicities and colors. You come a few steps closer to having gathered all cultures in one place. No cities are as close as Makkah and Madinah.

Football match near Mount Al Tundobawi, locals watched by large crowd of neighborhood residents 2017, courtesy of Abdullah Almalki.

The present. Now is what is important. Documenting the present means documenting the past in a way, and it is the building blocks that build the future in different ways.

Enjoy more of Abdullah Almalki works here:

Omran, Makkah 2017, courtesy of Abdullah Almalki.

Uncle Adel, Cairo 2022, courtesy of Abdullah Almalki.

Third expansion project of Masjid al-Haram, Makkah 2015, courtesy of Abdullah Almalki.