A ‘Rihla' through the desert

Photo by Scott Baldauf.

“See where the wind takes the sand? If the wind is from the north, it will fall toward the south. It’s easy. No need for GPS. Khali wali [let it go] technology,”

—Quriyan Al-Hajri, a man of nature and a member of a Bedouin tribe.

It was a warm Friday afternoon, and Quriyan Al-Hajri was walking quickly toward the north, as if he was on some kind of mission. Which, in fact, he was on—to plant a tree where his mother gave birth to him. But that was just one element of his mission.

His goal was ambitious this past October. Over the next three or four days, Quriyan would walk from his home in a village near Ain Dar to the place of his birth, 120 kilometers away near the historic town of Thaj. It’s a walk this 63-year-old retired Aramcon has taken several times before, but this year the stakes were somewhat higher. This year, he wanted to raise awareness about the degradation of the land of his birth over the past decades, which he believes is due to human behavior and growing desertification.

Quriyan Al Hajri is not a towering physical presence of a man, but what he lacks in stature, he more than makes up for with determination and enthusiasm. In his working years as a supervisor for Saudi Aramco’s Wellsite Services, he was the man managers sent deep into the Rub‘ Al Khali to build a road through the dunes to a new oilfield called Shaybah. Quriyan is used to tackling problems with a joke, a truck, and more enthusiasm than most people experience in a lifetime. And on this journey, like a modern Johnny Appleseed, Quriyan would plant native trees along the route in a single-minded effort to protect and restore the environment.

Born into a family of Bedouin herdsmen, some of whom took jobs in Saudi Arabia’s booming oil industry, Quriyan Al Hajri has retained knowledge that has been passed down for generations. He has an almost supernatural knack for knowing where he is in the desert, how to survive while he’s there, and how to reach his destination safely. Work colleagues from his days as a wellsite services supervisor often describe their tours of duty with Quriyan as a course in Bedouin 101. Saudi Arabia’s younger population may be increasingly comfortable with technology and excited by the ambitious goals of Vision 2030, but Quriyan argues that old-school desert knowledge is far from obsolete. It is still necessary for survival, and for knowing how to preserve the Kingdom’s fragile environment.

Through the Kingdom’s long history, Bedouin caravans were the lifeblood of the economy, carrying goods and ideas from city to city, oasis to oasis. City folk and nomadic caravan leaders were dependent on each other. Without city folk, there would be no buyers and sellers for the high-value incense and spices the nomadic caravans were transporting, and without the buyers and sellers, the nomads would be deprived of their livelihood.

Twenty-first century Bedouins like Quriyan Al Hajri may have adopted some of the trappings of modern society – smart phones, WhatsApp, and even health apps that measure one’s steps. But Quriyan feels an obligation to share what he knows with a younger generation, knowledge that may help Saudi Arabia to meet environmental challenges like desertification.

On his first day, Quriyan rose at 3 a.m., determined to start his journey before the heat of the late autumn sun kicked in. He washed up, said his early morning prayers, grabbed three bottles of water and headed out on the road.

He arranged to meet his driver, Awadh, eight hours later, near the village of Al Harra, a distance of some 30 kilometers away. The meeting place would be where the paved roadway ends, and where the white sand desert stretches in all directions with very few landmarks. From here onward, the only traces of life would be animal tracks in the sand, herds of camels, and the occasional truck leaving clouds of dust in their wake.

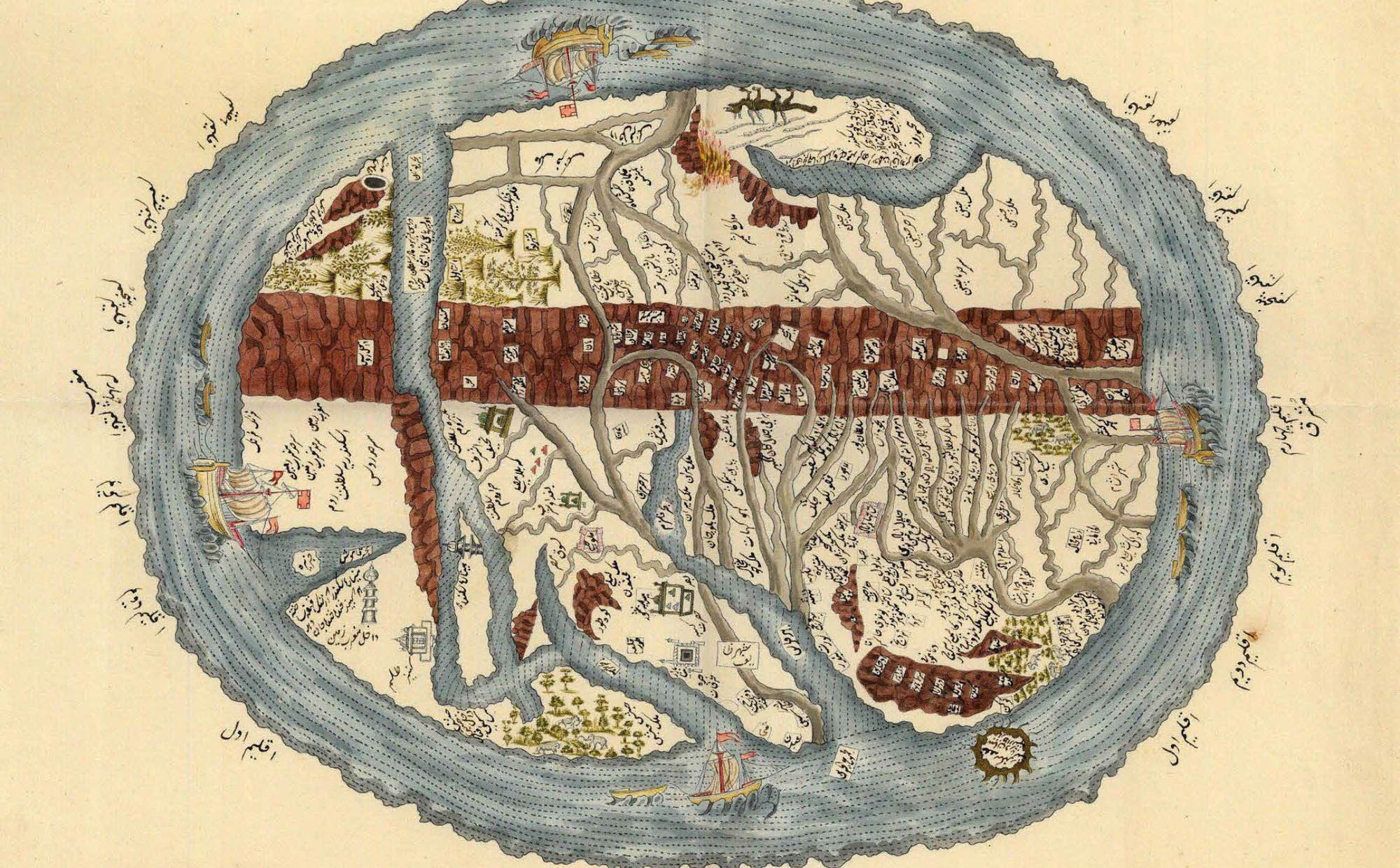

For his companions, who would meet him later that morning, Quriyan drew a map and sent it by WhatsApp – his one tech addiction. It looked like something out of the Lord of the Rings, with speckled areas indicating soft sand, specks and dashes for harder packed gravel, and pointy peaks to signify the jebels along the way. At the end of his journey was a peak called Jebel Al Bateel on the outskirts of Thaj. This was where Quriyan was born, 63 years ago.

But when Quriyan’s son Nasser, Awadh, and a guest reached the agreed-upon rendezvous, just after 11 a.m., Quriyan was nowhere to be found. They headed north 5 kilometers, then 10 kilometers. By the time they found Quriyan, close to noon, he had already completed 55 kilometers.“I did a little running,” he admitted, sipping a bottle of water in the shadow of the truck.

In the distance, downwind from the truck, Awadh began a fire to cook the day’s meal, a fragrant pot of camel kabsa.

How did he do it? How did he navigate the desert in the dark? And once the sun came out, how did his body adapt to the point where he could travel long distances in the desert with hardly any evidence of difficulty? It was all very simple , Quriyan said.

In the early morning hours before dawn, he guided his path by the stars. He knew the paved road was off to the west of his village, heading due north in the direction of Thaj. If he walked in a northwestern direction, keeping the North Star slightly ahead of him and to the right, he would reach the point where the paved road ends at Al Harra. And then, if he got there early, he would just keep going.

As the sun rose in the sky, he looked at other signs. Little ridges of sand formed like triangles on the desert floor, as the prevailing northern wind (shamal), carried sand across the desert floor. Heavy red-colored sand would get deposited first, and light-colored sand

would be blown across the ridges, or tufts of grass, and get deposited on the southern side.

Even if there are no ridges or tufts of grass, you can tell where the north is, Quriyan said. He picked up a handful of sand and watched it drop to the ground.

“See where the wind takes the sand?” he asked. “If the wind is from the north, it will fall toward the south. It’s easy. No need for GPS.”

“Khali wali technology,” he laughed with a dismissive wave of the hand.

The terrain between Ain Dar and Thaj is largely barren of vegetation, but Quriyan said it hadn’t always been endless seas of sand. This region had always been desert, to be sure, but there had once been plenty of scrub brush around, and the occasional small trees.

Quriyan took out his smart phone to show a photo taken in the early years of his career, some 40 years ago. The photo is of a landscape of low growing shrubs stretching out to the horizon, where there is a pair of flat-topped jebels in the distance. Quriyan pointed off in the direction he was heading, and sure enough, that same pair of flat-topped jebels is ahead of him. This is the same spot where the photo was taken. The only thing missing are all those shrubs.

Decades of overgrazing by ever-increasing herds of sheep and camels had nibbled that vegetation down to the ground, and eventually there was nothing left but sand.

Off to the northwest, Quriyan spotted a low-lying area that he called a sabkha, or dry lake bed, and immediately started walking in that direction. Behind him, Quriyan’s driver followed at a distance, with all the camping gear, food, and water, and a small collection of trees packed in the back.

It might feel a tad optimistic to plant a tree in the desert and assume it will survive. But Quriyan said he only plants native trees, and usually in places like this sabkha, where there is a ready supply of moisture just inches beneath the surface. He dug at the sand with his hand, popped the tree out of its pot and placed it in the hole, patting it down and covering it with water.

“I know I can’t solve this by myself, but I want to do what I can,” he said, promising to talk with some of the local herdsmen later to ask them to look after the trees he leaves behind. There might be many causes for the desertification, he said, from rising global temperatures, decreasing rainfall, or even too many animals on the land. But Quriyan said he would do his part to make things better. “It may be because of reduced rainfall, it may be because of too many animals, but we all need to do more to protect the environment,” he said.

Barren as it looked, the desert was alive. As he walked, Quriyan gave lessons in the sand. He taught how to identify the footprints of camels, with their two pointy toes in the front and round heels in the back; foxes, with their small front paws and larger back paws; beetles, with their multiple tiny footprints; and large desert lizards, with their tails and triangle-shaped clawed hands.

Daytimes had their rhythm, clocking 15 kilometers in the morning, and another 15 kilometers in the afternoon. Breaking up these long walks were small stops for prayer, lunch, and the occasional nap. As the sun sunk in the sky each night, Quriyan would find a soft sandy area to lay out our sleeping bags for the night. And as a protection against wild animals and AlJinn Quriyan would demonstrate

an old Bedouin tradition of drawing a circle in the sand around his campsite, reciting a Qur’anic prayer of protection, the Ayat al Kursi. Then his group would fall asleep under a crystal-clear sky, the Milky Way and millions of stars stretching above them like a veil.

For the record, there was no sign of animal footprints crossing that line at night.

On the third day, Quriyan reached his main destination: the flat-topped Jebel Bateel al Janub on the outskirts of Thaj, where Quriyan was born. Sixty three years ago, Quriyan’s mother woke up feeling birth pains. It was still dark outside, and no one was awake, so she walked two kilometers to the base of Jebel Bateel, took cover under a pair of trees, and gave birth to Quriyan. Not having a knife, she cut the umbilical cord with her teeth, tied off the cord, returned to her tent, with Quriyan wrapped in her scarf.

The only sign of those trees today is a pair of stumps, probably chopped down for firewood years ago.

Under a strong afternoon sun, Quriyan offered a prayer for the country of his birth, for the people who live in it, and for the environment. And then he planted one last tree, before heading home.