Okaz, where the Wordsmiths of Arabia met

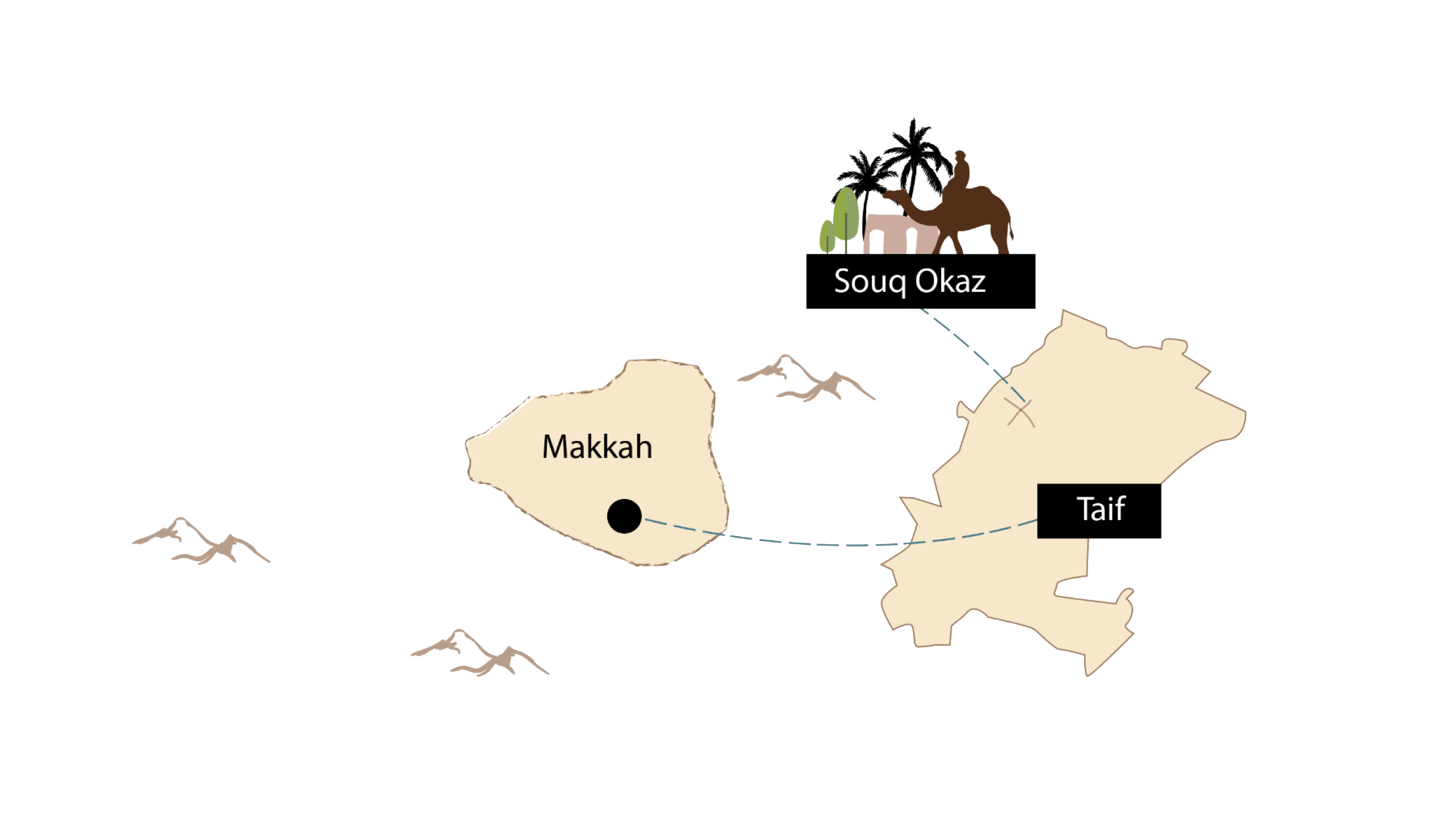

Souq Okaz (located 40 kilometers north of Taif) was one of the three major souqs of the pre-Islamic era, and most accounts outline a sacred procession of visiting each souq during the holy months of Dhul-Qidah and Dhul-Hijjah, culminating with pilgrimage at Makkah. As an old saying went, “Do not attend Souq Okaz, Mijna and Dhil-Majaz unless you’re in a state of for pilgrimage.”

The word okaz can be translated in many ways, but roughly means preaching, boasting and arguing,which is an especially apt description of the activities that happened there. Apropos of the souq’s name and legacy, even the Prophet had gone there each year to preach to the people about Islam And while the location thrived as a marketplace for foods and goods from all around the region, it also served

as a meeting spot to formalize tribal laws, announce truces, and host a variety of arts and sports competitions (predominantly fencing and riding). Still, the fame of Souq Okaz lies with its oratory competitions and its key role in crafting the Arabic language. It’s rare, if not unheard of, that you can pinpoint a physical location where a language was officially tweaked and honed each year through the efforts of literal wordsmiths from around the Arab world.

For Arabs of the time, there was no sharper weapon than your own tongue. One of the highest praises a tribe could give would be to its most eloquent orator. It’s no wonder that the specific miracle of Islam’s Qur’an would be linguistic, directly matching what the people would admire the most.

There is an empowering story that happened at Souq Okaz one year, centered on one of the most famous female poets of the pre-Islamic era, Al-Khansa (whom by several accounts is also considered to be the Prophet’s favorite poet). She had participated in a poetry competition presided over by Al-Nabighah Al-Dhubyani, one of the preeminent poets of the time, and who had judged in her favor that, “Were it not for the poet Al-A’sha before you, I would’ve proclaimed you the greatest poet among all humans and jinn alike.”

Another poet, Hassan ibn Thabit, scoffed and countered, “I am better than both you and her.”

So, in the spirit of the event, Al-Nabighah asked Al-Khansa to engage and rebut Hassan’s boast. She asked Hassan about his favorite verse from the poem he had presented earlier, and when he recounted it, she proceeded to methodically and definitively dissect it by pointing out seven specific literary flaws that could be improved upon. In what one must assume is the ultimate sign of losing an oratory battle, Hassan was speechless.

Souq Okaz ran every year for nearly two centuries. However, with the rise of Islam, new trade routes and new cities in Egypt, Iraq and the Levant region, the market quickly lost relevance until it was ultimately destroyed in 725-26 CE.

Nearly 1,300 years later, it was revived in the same spot in 2007, each year honoring a different poet. They have lectures, sports, poetry, art, and, of course, a thriving marketplace 200 shops strong. People would even dress up and portray famous characters of the past to immerse visitors in how the Souq was in its heyday. And, true to the original intent of the Souq, this isn’t simply a Saudi affair. Just last year, 11 Arab countries shared space at the event to showcase their heritage and cultural traditions.

Next time you hear about it happening, definitely try to make it out there and experience a taste of our impressive oratory legacy, where poets battled it out and crafted the language of Arabia.

Ahmad Dialdin, a Saudi Editor and senior feature writer, who writes about art and culture. He also works at the Ministry of Culture.